Lesotho Water Realms is a visual research project developed by Milan-based architectural office AOUMM. It analyses the ownership and consumption of water of this African country through geopolitical and sociological lenses, focusing on the power of rituals. Lesotho Water Realms is showcased in one of the International Pavilions at the 23rd Triennale Milano International Exhibition. Specifically, the exhibition aims to draw attention to the country’s unique water condition. All of Lesotho’s water is currently sold to neighbouring South Africa at a price of around 70 million euros per year. Whilst this provides South Africa with 95% of the country’s water needs, 90% of Basotho suffers from water scarcity and accessibility. In this interview with AOUMM’s founding partners Luca Astorri and Matteo Poli, we discuss the incipit of the research, the value of undertaking architectural research and the importance of cultural institutions like the Triennale - spaces where it is possible to discuss and shine a light on these overlooked dynamics.

KOOZAOUMM is a design firm operating within the domains of architectural, landscape, urban, interior, and exhibition design”, why are you interested in Lesotho?

Luca Astorri | Matteo Poli As architects operating within the framework of the AOUMM office, we always look to a deep and critical understanding of the notion of context which - if we simplified from the abundant literature existing on the subject - means that whatever one does will be interwoven with what was there before. We believe that context is even more relevant when undertaking research in-person, fieldwork, as one is inevitably linked to the place they are observing. Thanks to the NGO Rise International (www.riseint.org), the AOUMM team has been involved with the country of Lesotho since 2017. Specifically, Luca Astorri is the founder and co-director of the NGO’s design and built training program called “in loco”. It operates in the country and develops several projects related to social needs, growth, schooling, architecture and landscaping, fostering young entrepreneurship in the building environment.

Landscape, rituals and infrastructures were the most appropriate entry points as they incorporate the design of the anthropic environment, the inner milieu of humans, the superimposition and the physical evidence of financial investments in a country.

KOOZ Lesotho Water Realms is a visual research undertaken at three scales which spans from the geopolitical to the sociological. What informed this multidisciplinary approach? Could you draw parallels/connections between these scales?

LA | MP When we started working on Lesotho Water Realms, we had extended discussions on which lenses we thought appropriate to interpret the country's water bodies. When reorganising the information collected, we explored many diverse hypotheses and ultimately decided that landscape, rituals and infrastructures were the most appropriate entry points as they incorporate the design of the anthropic environment, the inner milieu of humans, the superimposition and the physical evidence of financial investments in a country.

Water is the centre of Lesotho's identity: it emerges everywhere. It flows through it all. Having altered water flows for the benefit of South Africa in an exchange that is typical of the global market - divided into negotiations, compensations, and massive infrastructure investment - means transitioning public bodies of water into privatised resources. Water is sometimes visible but not accessible equitably and uniformly, it remains, however, a real common good: for subsistence agriculture; for the more remote villages, often causing exposure to violence and risks for the women who harvest it; for the spirituality between waterfalls and caves, where each drop embodies a sacred and ancestral value.

Water is sometimes visible but not accessible equitably and uniformly, it remains, however, a real common good: for subsistence agriculture; for the more remote villages, often causing exposure to violence and risks for the women who harvest it.

Lesotho Water Realms is an ongoing visual research on a geopolitical and social scale, that offer the visitor three-dimensional scales to understand the country. A colossal one related to the global infrastructures of the dams, one related to the landscape, where water for Mosotho scarcely flows and lastly, an immaterial one, visualising bodies of water in the traditional rituals of Basotho culture.

Water-rich Lesotho irrigates and keeps arid South Africa alive thanks to the Lesotho Highlands Water Project (LHWP), which is supposed to benefit both countries: South Africa pays Lesotho an annual fee for the water it takes from its rivers, while the small kingdom in the highlands uses dams to partially generate the electricity it needs. Lesotho's government has accomplished an incredible infrastructural feat in its scale and ambition, diverting almost all the water from the mountains to South Africa. Still, the Basotho people have been severely deprived of water and generally suffer from progressive environmental decay linked to erosion and runoff of fertile land. The second phase of the LHWP began only three years ago: five new dams were built to send even more water resources to South Africa.

The Basotho people have been severely deprived of water and generally suffer from progressive environmental decay linked to erosion and runoff of fertile land.

KOOZ What was the most significant data collected when undertaking the research? How did it then inform the trajectory of the research?

LA | MP An extensive collection of data informed both our research and its formalisation as a Pavilion at the Triennale. Nevertheless, to date, the most astonishing discovery encountered when undertaking the project was not related to quantity but to the supernatural. The primary divinity of traditional Lesotho religion is a water snake whose representation appears in every cave in the country. When we came across this discovery, we immediately printed a large-scale reproduction of the drawing and hung this in our office. With a feeling of discomfort, we realised that the GIS outline of the dams resembled the emersion of the water snake above the land. In Basotho’s oral tradition, when the snake emerges, it is said that this will bring destruction and pain, which one can probably associate to the erosion of soil and flash floods which have been affecting the country since the creation of the former.

An extensive collection of data informed both our research and its formalisation as a Pavilion at the Triennale. To date, the most astonishing discovery encountered was not related to quantity but to the supernatural.

KOOZ The exhibition in Triennale features two large GIS images which reveal how the dams have altered the landscape of the country. Could you tell us a little bit more of the reasons behind the construction of these dams and their impact on the territory?

LA | MP South Africa has always been a thirsty country, especially the Gauteng region and the Johannesburg metropolitan area, where about 20% of the population resides producing 40% of the country's GDP. South Africa is the wealthiest country in southern Africa and has always had a position of hegemony both in the region and within the Southern Africa Development Community (SADAC). The latter places water as the primary tool for the development and prosperity of the sub-continent. With this premise, in 1986 South Africa -still under the apartheid regime - signed an agreement with Lesotho for the extraction and transfer of water from the country (called “transboundary water transfers”) to meet the needs of the Johannesburg’s metropolitan area. As previously explained Lesotho receives annual payments of about 70 million euros in return, nothing compared to the benefits of South Africa. Consequently, the Lesotho Highlands Water Project (LHWP) was born, along with the construction of a system of dams to create a reservoir to export water through an 80km-long tunnel. At the centre of this dam system - the project is expected to be finished by 2030 - is Katse Dam, the research focus of the pavilion. LHWP is ultimately the centrepiece of hydro politics in Southern Africa.

Lesotho, GIS images generated by 1995 and 2022 data. Courtesy of AOUMM.

KOOZ Beyond the unique condition of Lesotho, how does the research address a larger issue connected to the ownership and consumption of water?

LA, MP The water issue in Lesotho is peculiar. One would generally assume that the owner of a good is a monopolist. However, in this case, the monopolist is the user whereby there is a sort of reverse monopolistic market where privatisation happens by the physical landlocking of Lesotho by another country, South Africa. By observing Lesotho, we had the possibility of reflecting on how commodities shape politics even more than finance, goods, consumerism, etc. We believe we live in a post-consumerist society. We live in an era where raw materials - with the little economic impact they have on large parts of the global population - dominate and will shape the future: right now gas, not an industrial product or a manufactured good, is affecting European policies in light of the current Russo-Ukrainian conflict. Strikingly, in Lesotho the percentage (8%) of people that benefit from selling water to South Africa is equal to the percentage of people that benefit from diamond extraction.

We had the possibility of reflecting on how commodities shape politics even more than finance, goods, consumerism, etc. We live in an era where raw materials dominate and will shape the future.

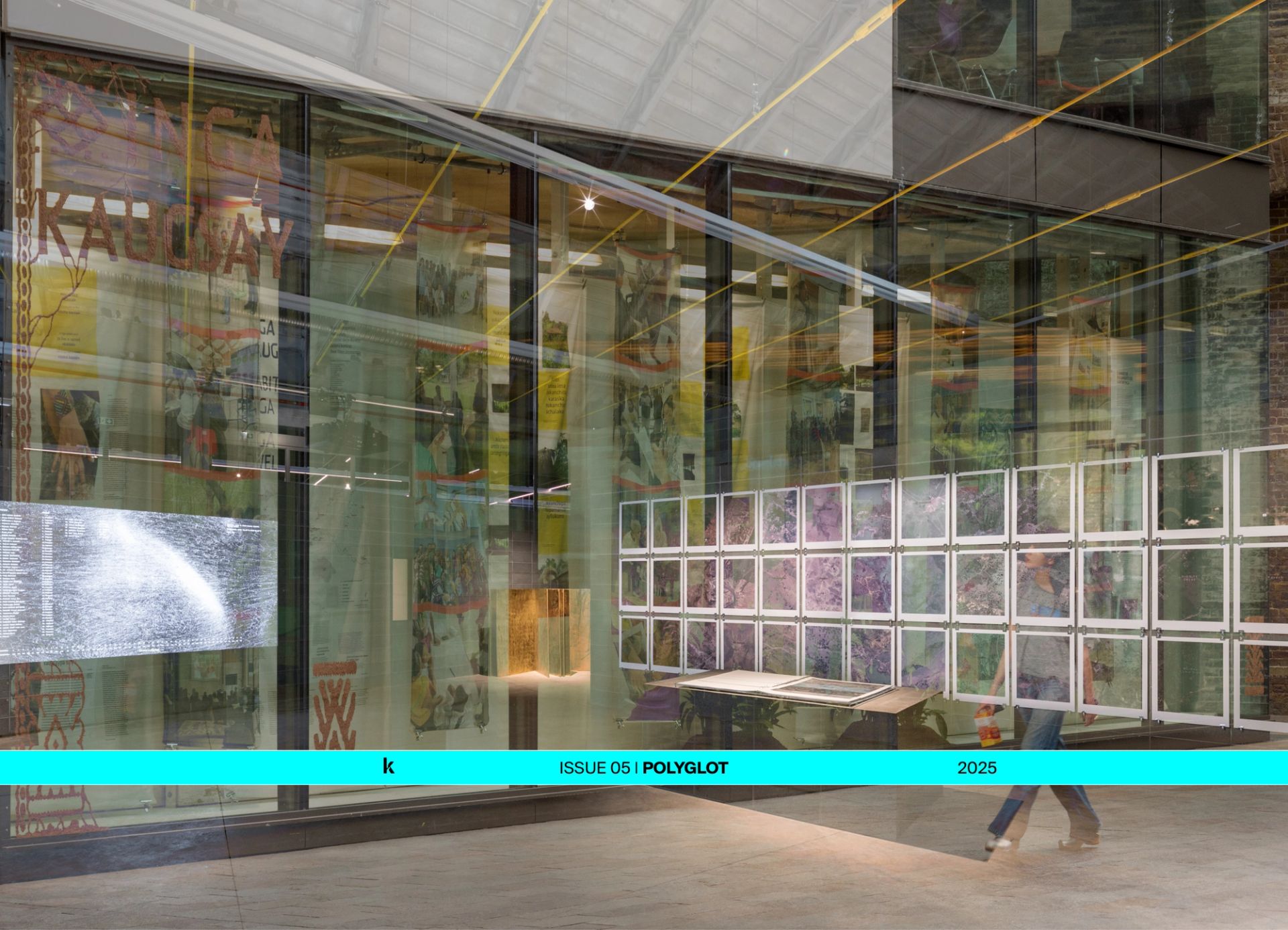

KOOZ AOUMM has been invited to present the project within the XXIII Triennale di Milano International Exhibition, what is the potential of showing this project in this context and to its audience?

LA, MP We think our Pavilion is somehow an alien in the parterre of this year's Triennale due to its extremely political ambition and because of our simple yet strong statement in response to the title "Unknown unknowns" of this year’s Triennale edition. Not many people know the country of Lesotho, and nobody has looked at it as the central water reserve for the most developed country in Africa. By designing an exhibition that can both be seen in 10 seconds, by observing the two carpets that feature comparative GIS images generated by 1995 and 2022 data: visually depicting the changes in the landscape, or by reading the extensive visual map printed on wallpaper we aimed at drawing attention to an unknown country and its unknown or undercover exploitation.

The Triennale also offers an opportunity to showcase a little-known country and helps contextualise an issue - that of water - much debated and feared as a future cause of possible wars to an audience of journalists, architects, designers, curators and beyond. On the other hand, it is both an opportunity to raise awareness about the water issue and, more generally, about the exploitation of resources in this region and in others, and an opportunity to create a network of professionals interested in collaborating with the NGO. This includes people open to supporting the NGO in various ways, scholarships for local students, donations and so on.

Not many people know the country of Lesotho, and nobody has looked at it as the central water reserve for the most developed country in Africa. [...] we aimed at drawing attention to an unknown country and its undercover exploitation.

KOOZ How and to what extent can architecture-based research tools trigger political action on imminent issues that are affecting our Planet?

LA, MP As architects we are constantly confronted with issues related to the notion of representation. We don't think we can critically observe and understand everything we look at, but we believe that, embedded within the figure of the architect, is the desire and ambition to make conditions and phenomena understandable. That's why AOUMM, beyond traditional commissions in architecture and landscape, has and is involved in many unusual projects which span from the translation of an artist's sketch into real (for Alfredo Jaar, Vanessa Beecroft and many other artists), to the realisation of carbon fibre domes for experiments with nanoparticles (in collaboration of the University of physics and the European Commission), to the design of landscapes based on sound waves (for Kanye West in Los Angeles).

To map is a noun, a verb, an object and an action simultaneously. Representation is the tool to investigate issues related to architecture and broader and more complex problems, such as geopolitics in this case. Mapping, for example, has historically had enormous importance in defining political, economic and social questions and boundaries, but it is also a tool for knowledge. The simple representation of two moments of the same area has a powerful and profound meaning that goes beyond the image itself. The dam's exact water level mapping concerns the loss of arable land, disappearing villages, people and communities uprooted from their places, along with environmental issues and soil erosion. In this sense, mapping involves political action...

Katse Dam, Lesotho, aerial view, 2021.

We don't think we can critically observe and understand everything we look at, but we believe that, embedded within the figure of the architect, is the desire and ambition to make conditions and phenomena understandable.

Katse Dam, Lesotho. Credits: Giada Zuan.

Bio

AOUMM (Argot ou la Maison Mobile) is a design firm operating nationally and internationally within the domains of architecture, landscape and urban design, developing projects where different expertise triggers unexpected synergies. The firm is based in Milan and led by founding partners Luca Astorri, Riccardo Balzarotti, Rossella Locatelli and Matteo Poli.

Since 2010 Luca Astorri has gained extensive experience working with several NGO’s following architectural projects and research on informal settlements in Egypt, Kenya, Tanzania, and South America. Since 2017 he has been a member of Rise International NGO, an NGO based in Lesotho for which he founded and co-directs the In-loco program, a fellowship base on learning by doing process.

Since 2005, Matteo Poli has been working as a researcher in Landscape Architecture at the Politecnico di Milano. From 2004 to 2007 he was editor at Domus and then special correspondent for the magazine Abitare, where he currently writes.

Federica Zambeletti is the founder and managing director of KoozArch. She is an architect, researcher and digital curator whose interests lie at the intersection between art, architecture and regenerative practices. In 2015 Federica founded KoozArch with the ambition of creating a space where to research, explore and discuss architecture beyond the limits of its built form. Parallel to her work at KoozArch, Federica is Architect at the architecture studio UNA and researcher at the non-profit agency for change UNLESS where she is project manager of the research "Antarctic Resolution". Federica is an Architectural Association School of Architecture in London alumni.