It is rare to find an architectural representation that is as clear, radical and thoughtfully made as the project itself. Such is Blue by Malkit Shoshan, an ambitious volume that outlines her 15-year-long research into the architecture of the UN Peacekeeping Missions around the world. It investigates how these United Nations Missions - which take the form of large-scale camps - should be studied for their spatial footprint, use of resources and architectural form in order to prevent the depletion of the communities which they are meant to serve. Observing dozens of sites across the Middle East, Southern Europe and Africa, Shoshan argues that the architecture of these camps needs to be completely rethought not only in terms of its deployment but also in terms of its closure at the end of a mission: in a radical move, she suggests that these expensive islands of equipment and infrastructure should not be deconstructed, trashed into a landfill, or in a good case, packed and sent back to Europe; perhaps, careful planning of their initial layout, technology and typology would mean that after the mission had run its course, the perimeter walls could be lifted and the camp could (eventually) dissolve into the local fabric and serve the local community. Like the Roman camps that have now become Paris and London, Shoshan asks - perhaps the cities of the future are the UN bases of today?

Like the Roman camps that have now become Paris and London, Shoshan asks - perhaps the cities of the future are the UN bases of today?

This sort of investigation is not as simple as it sounds. Questioning the legitimacy of something which sounds as promising as a “peacekeeping” - even portraying it as a symptom of the White Saviour - requires a multidisciplinary approach. For this purpose, Shoshan operates with her think-tank FAST: Foundation for Achieving Seamless Territory, which has been active since 2005 in using “research, advocacy and design to promote social, spatial and environmental justice, equality and solidarity.”1 For Blue, FAST brought together military engineers, urban planners, anthropologists, human-rights activities, architects and diplomats that could re-examine the spatial relationship between the UN bases and their surrounding context. It looked into compounds, camps, logistical hubs, checkpoints and electrical and water infrastructure that were “built swiftly under the auspices of a UN peace mission,” in the words of Shoshan, without considering the local built, human landscape or the environment. As of 2020, there are active peacekeeping missions in 13 countries around the world, in over 150 African localities (including both rural and urban sites). “These missions are deployed in some of the world’s most impoverished areas” Shoshan writes, “where issues of perpetual armed violence, extraction and dispossession, and extreme climate conditions converge.” In this colonial condition, the UN missions are often larger than the cities that they are meant to protect, rising in the words of Shoshan “like fortified islands” that disrupt existing texture, block transportation, absorb urban infrastructure, and pollute the soil, air and water bodies. A solution would therefore have to expand into other disciplines, amongst them economics, human rights, military engineering and ecology. In that process of expansion, Shoshan argues, “design tools became the vehicles for highlighting the connections between these fields and how they are being consolidated, materialised and synthesized in space.”

The UN missions are often larger than the cities that they are meant to protect, rising “like fortified islands” that disrupt existing texture, block transportation, absorb urban infrastructure, and pollute the soil, air and water bodies.

As Walter Benjamin writes, “He who wants peace should speak of war.”2 In her introduction, Shoshan cites Benjamin alongside other philosophers in order to define not only peace but also what is war and violence, including not only armed conflicts but also social injustice in terms of the distribution of wealth, exploitation of human labour, and extraction of natural resources. The UN, as a highly hierarchical organisation of “exclusionary practices, [and] power dynamics”, in the words of Shoshan, should question its own legacy before claiming its own agency in peacemaking, building or keeping. Following this trajectory, the book positions the history of peacekeeping along a line with the first European expeditions to Africa, thus linking the UN missions with colonial excursions.By diving into this history, Shoshan positions her inquiry into the architecture of UN camps within a social, historical, and political context, linking the spatiality of a mission to the ideological paradigm of modernism and imperialism; resource extractions, trade routes, and supply chains of past centuries are at the root, she argues, “of many of the conflicts that have shaped people’s lives, nature, and large ecological systems across Africa and the world.”

The UN, as a highly hierarchical organisation of “exclusionary practices, [and] power dynamics” should question its own legacy before claiming its own agency in peacemaking, building or keeping.

Design (and) Activism

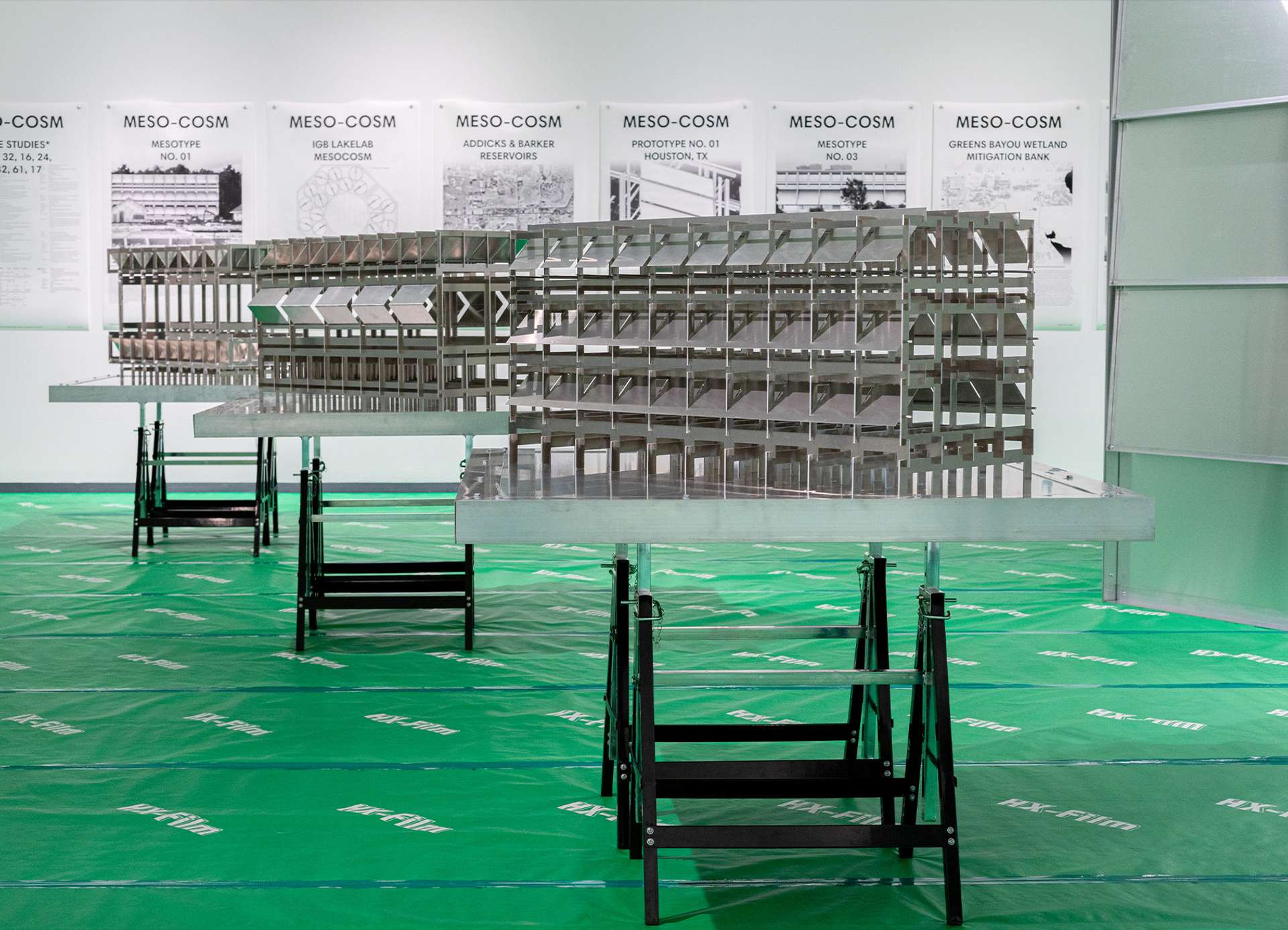

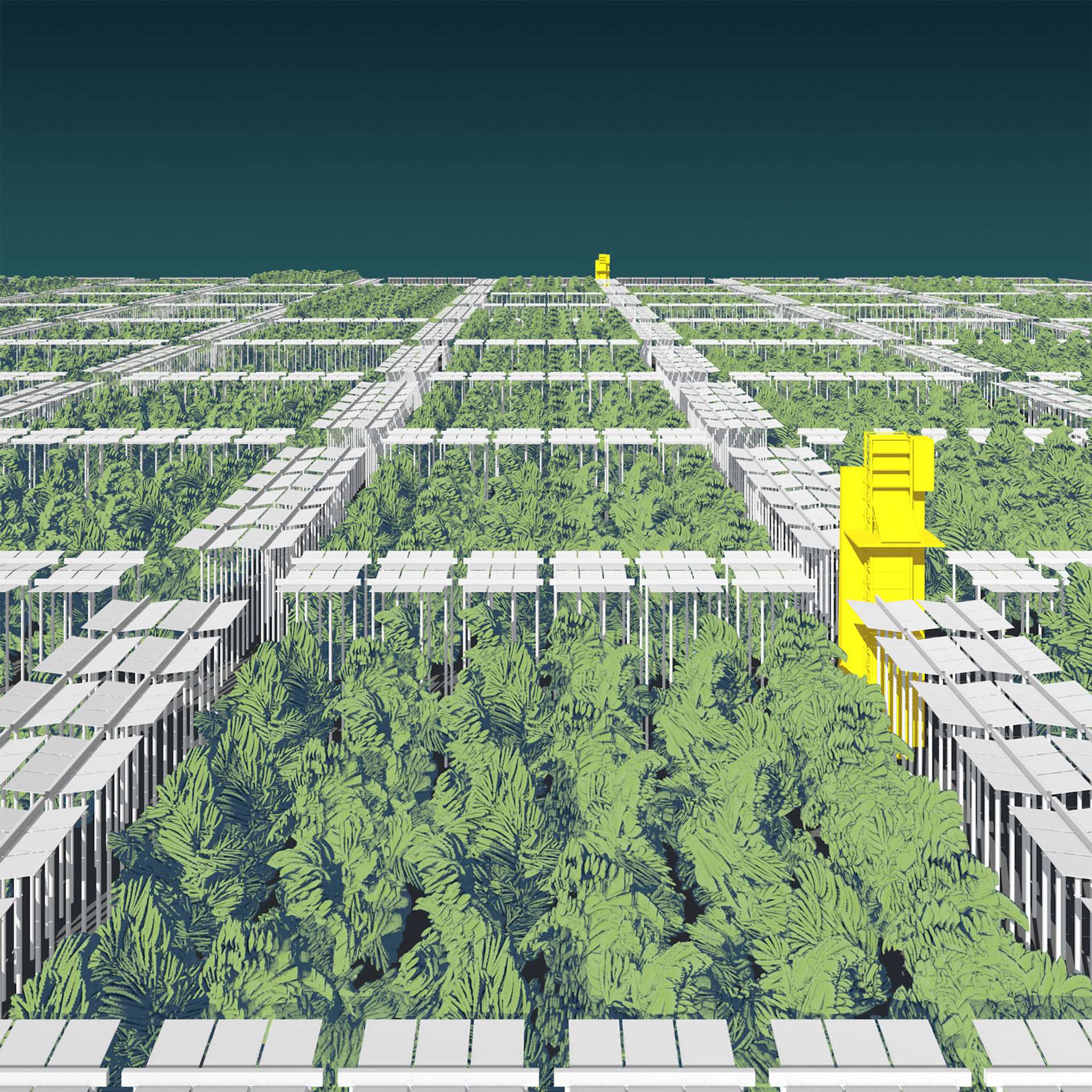

The second and third parts of the book dive into various case studies of UN missions, dissecting their operational methods using compelling text and visuals.Designed by the Dutch bookmaker Irma Boom, the book is richly illustrated with materials collected on Shoshan’s field trips to Africa as well as over a decade of archival research. It includes original and historical photographs, annotated satellite images, study models, video stills, transcriptions of interviews with UN officers, and conversations with locals. Pages 344-361 show photographs and analysis of physical models created by FAST that propose design processes for future takeovers, considering the present condition of the site, the deployment of the UN base, and the gradual cross-dissolving between the two spatial entities as a mission comes to an end. Perhaps the most impressive visual component is Shoshan’s elaborate cartographies of data, a method she has been using since her award-winning book “Atlas of the Conflict: Israel-Palestine.” In Blue, she uses drawing of various scales to illustrate complex sociospatial conditions (such as availability of water, scales of camps, territorial and migration shifts, or percentage of literacy) with clarity and legibility, becoming a form of architectural practice in itself. Pages 60-65 for example, showcase “The Changing Face of War and Peace” - a visualisation of UN expenditure on missions in Africa as intersected with the geographic location, timeline, size of the population, and the percentage of refugees. Other such graphics also depict the presence of UN forces vis-a-vis the local conditions of rainfall, urban expansion, sea level rise, waste and sanitation infrastructure, the availability of water and food, emission of gas and more.

Shoshan uses drawing to illustrate complex sociospatial conditions (such as availability of water, scales of camps, territorial and migration shifts, or percentage of literacy) with clarity and legibility, becoming a form of architectural practice in itself.

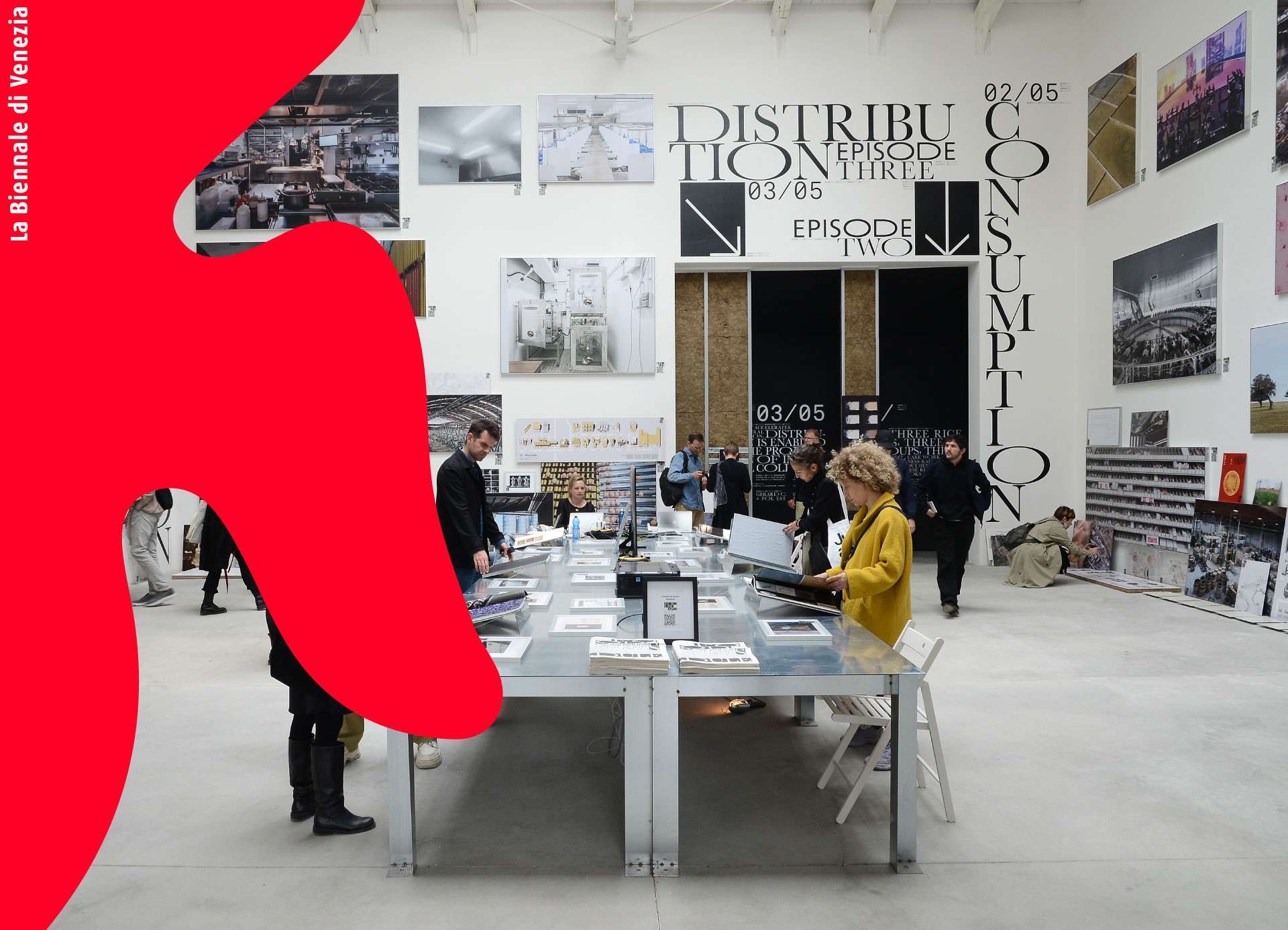

Comparing such large amounts of data makes this research legible not only to architects and spatial practitioners but also to civil servants, politicians and journalists, which are addressed through other platforms. In 2016, Shoshan curated the Dutch Pavilion at the Venice Architecture Biennale under the title “Blue,” focusing on a case study in Mali (which is further elaborated on in the book). This stage gave Blue an opportunity to address a wider audience that included the Dutch Chief of Defense, who was surprised by the “scale and by approach to data and space,” and sought to implement some of the proposals in the Dutch Ministry, NATO and the UN. Following the exposure at the Venice Biennale, Blue infiltrated the corridors of political and diplomatic institutions, resulting in an exhibition of the project at the UN headquarters in New York City. The exhibition “Blue: Islands in Cities,” was installed by FAST next to the UN Security council chamber, allowing for maximum exposure amongst those responsible for the institution’s vast impact on the world. This gave Blue agency in disseminating the ideas investigated by FAST directly to high-ranking policymakers. If in doubt about their success, one needs only to read the UN’s resolution (released in January 2017) that directly addressed the issues raised by Shoshan’s research. Their statement includes specific attention to the material after-life of the camps, acknowledging that “co-use” and “after-mission-use” is crucial. Most importantly, the resolution acknowledges that post-departure usage is only possible “if the facilities are constructed in such a way that they fit within the local culture and can be maintained, after mission’s departure, through locally available resources.”3 The importance of this UN resolution cannot be overstated: it shows how FAST’s research into the spatiality of peacekeeping missions caused a paradigm shift in the way this great body of power will approach its future footprint, infrastructure, and design of its outposts in the world.

Blue - both the book and the project - is a rare bird. It addresses directly issues of sustainability, colonial legacy and human care by confronting a large institution through its own policy. It is both a research, a practice and an activist project.

Blue concludes with tangible recommendations for the future of the UN’s peacekeeping operations that are divided into short, mid and long-term assignments. With this outcome, Shoshan had managed to breach the schism between research and the “real world.” This practice, which Shoshan calls “design activism,” is present in her teaching work at the Harvard Graduate School of Design. Other projects include Village: One Land Two Systems, where she worked with artists to achieve recognition for a displaced Palestinian village in the Carmel Mountian, designing its master plan and first community centre. More recently, she lead research into the politics of fertility,resulting in the exhibition and publication entitled “Love in a Mist.” Other projects include her recent inquiry into Border Ecologies and the Gaza Strip, which awarded her a Silver Lion at the 2021 Venice Architecture Biennale. These exhibitions join Blue as something which is beyond a research and design project: it is an experiment in activism.

Blue - both the book and the project - is a rare bird. It addresses directly issues of sustainability, colonial legacy and human care by confronting a large institution through its own policy. It is both a research, a practice and an activist project, demanding those in charge to be accountable for what they leave behind. It shows that global problems do not require grand solutions, but nuanced observations on processes, surgical interventions in policies, and the courage to expand the discipline beyond the familiar channels of intervention and collaboration. Blue shows how architecture can contribute directly to social, political and cultural change. If we return to the definition of peace as not only the absence of war but also a socially-just distribution of resources, power and labour, then Blue is perhaps one of the most successful operations of peacemaking in itself.

Link to the book: Malkit Shoshan, Blue: The Architecture of UN Peacekeeping Missions (Actar Publishers, 2022)

Bio

Gili Merin (Ph.D.) is an architect and photographer based in Vienna and Tel Aviv. Formerly the head of History and Theory at the Royal College of Arts (RCA) and a Diploma Unit Master at the Architectural Association (AA), she is currently a post-doc fellow at TU Wien and a lecturer at the SCE Negev School of Architecture. Gili lectured and led workshops at various academic institutions including the Harvard GSD, TU Delft, Central Saint Martin and Syracuse, Aarhus, Rice, Carelton, and Aalto Universities. Her writing and photographic projects have been published in various journals and newspapers including the Economist, AA Files, MIT’s Thresholds, Plat Journal, The Guardian, The Architects’ Journal, and the Architectural Review.

Notes

1 “The Foundation,” FAST, accessed December 4th 2022, [link]

2 Walter Benjamin, Peace and Commodity (1926), Cited by Malkit Shoshan, Blue: The Architecture of UN Peacekeeping Missions (Actar, 2022), 12

3 Shoshan, Blue, 10