One of the internal themes informing the second edition of the Sharjah Architecture Triennial, directed by Tosin Oshinowo, was described as Extraction Politics: framing practices that deal with the serious material, social and political consequences of extraction, and highlighting innovative design methodologies which look towards rehabilitation and reuse. Among those listed within this theme are the Uganda-based initiative BUZIGAHILL and the Ecuadorian architectural practice Natura Futura. We had the opportunity to listen and learn from both, in the interview below.

KOOZ BUZIGAHILL studio in Kampala directly addresses the problems of fast-fashion and waste-colonialism. For the Triennial, you recreated the production studio of BUZIGAHILL and performed the act RETURN TO SENDER, whereby redesigned garments — made from second-hand clothes sent to Uganda — are sold back to the Global North. Disturbing images of fast fashion dumpsites across Kenya, Ghana and Chile reveal the environmental side of the problem, yet waste colonialism has also significantly impacted the Ugandan textile industry. Could you start by introducing us to this dual threat?

BOBBY KOLADE/BUZIGAHILL (BH) Every way you look at it, the second-hand clothing supply chain is flawed and exploitative. There’s a clear power dynamic which speaks to colonialist methodologies. You mentioned the environmental and industrial or economic impact – we argue that there’s social and cultural damage which may not be reversible. In Uganda, in the Global South, we are now fast fashion consumers as well. Our dress codes and the speed at which we consume fashion is defined entirely by consumption patterns in the Global North. I cringe when I see Ugandans wearing T-shirts with German slogans. We’re experiencing a complete cultural suffocation caused by the second-hand clothing trade.

"Every way you look at it, the second-hand clothing supply chain is flawed and exploitative. There’s a clear power dynamic which speaks to colonialist methodologies."

- Bobby Kolade, founder of BUZIGAHILL

KOOZ Centuries ago, Ecuador’s Babahoyo River and its floating houses were one of the main collection, storage, and rest points on the commercial route between Guayaquil and Quito. Presently, this route has ceased, and the number of floating structures has dwindled from 200 to 25, despite being recognised as an Ecuadorian heritage site. Natura Futura, what brought about the closure of the route and what is the cultural impact in the reduction of these floating structures?

NATURA FUTURA (NF) Commercial activity on the Babahoyo River began to decline at the end of the 19th century, with the construction of the new trans-Andean railway in 1872. Although river commercial activity continued during the following decades, it is from 1950 — alongside the first banana boom, the construction of roads and adoption of large, imported trucks — that the use of the river as the main means of commercial transportation declined greatly.

"Thanks to the national and international collaborations, we have, little by little, caused governments to turn their gaze towards floating communities; creating public policies that protect them and allocating public investment to improve their basic infrastructure."

- Natura Futura

Although commercial activity has faded, its history has left behind customs, systems and a strong culture that lives off the river and inhabits floating systems that live by and for the river. Unfortunately, the governments responsible for its care have not focused their efforts on cultivating and making this culture visible; rather, they have displaced or relocated them to housing complexes, ignoring that such actions potentiate family disintegration, uprooting from productive and geographical activities, cultural destabilisation and negative psychosocial effects on girls and young people. Thanks to the national and international collaborations, we have, little by little, caused governments to turn their gaze towards floating communities; creating public policies that protect them and allocating public investment to improve their basic infrastructure.

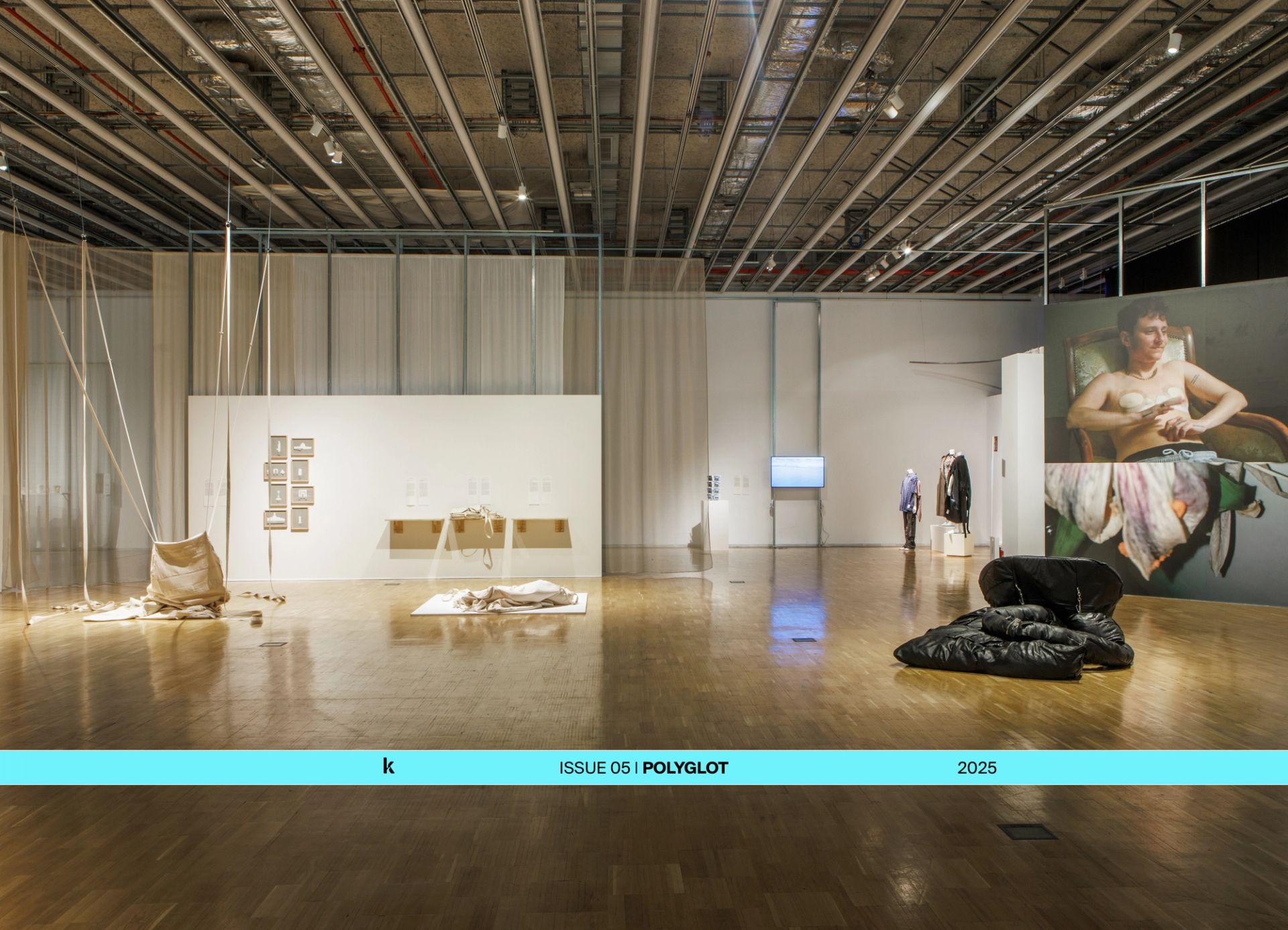

Natura Futura, La Balsanera - Productive Floating House. Sharjah Architecture Triennial 2023, Extraction Politics. © Francesco Russo.

KOOZ At SAT, BUZIGAHILL produced all the totes and bucket hats, which entailed sourcing more than 1,700 pairs of jeans from the hundreds of bales that were sent to the country from western countries. Here the medium is the message. What opportunities can arise when rethinking waste streams?

BH Traditionally, there is not much waste in our communities. Go to Owino Market and you’ll see women sewing children’s shorts using unsellable fast fashion waste. You’ll see furniture makers collecting scraps and offcuts which they use as a filler for couches. The ironing stations are built using repurposed materials. The word resourceful has been misused greatly in the poor African context; we’re naturally excellent at managing materials and resources. That’s not poverty, that’s wisdom. The problem is our inferiority complex and the assimilation of western lifestyles — the single greatest cause of waste — instead of an appreciation of the beauty of our own ability to reuse and redesign. At the core of everything BUZIGAHILL does is the desire to see a shift towards pride in ourselves on a national scale, because of what we’re capable of producing with our inherent wisdom.

"We’re naturally excellent at managing materials and resources. That’s not poverty, that’s wisdom. The problem is our inferiority complex and the assimilation of western lifestyles — the single greatest cause of waste."

- Bobby Kolade, founder of BUZIGAHILL

NF We believe that the idea of rethinking “waste” can be extrapolated to all aspects of design, from fashion to architecture — such as the use of agro-industrial waste to improve thermal comfort in built projects. We believe that the opportunities revealed by this approach are not only aligned with possible environmental improvements, but with a change in a new generational approach; a change where trends and fast-paced “fashions of the moment” will no longer hold any value for a generation committed to the responsible use of resources, from their extraction to their reuse. This is an opportunity to understand that any type of waste is a design error.

KOOZ For the Triennial you used the exhibition resources to rehabilitate one of the floating houses for a family which has lived on and been sustained by the river for more than 30 years. What is the potential of rethinking triennials and other exhibition platforms beyond their physical sites to impact distant geographies?

NF We believe that platforms that showcase creative ideas are the ideal space to establish a manifesto. Taking into account the main idea of the curator Tosin Oshinowo, we focused on what SAT was giving us, and what that could mean as a resource. Our question: Where is this resource most valuable, or where will it have the greatest impact? The answer was clear: we had to take it to Ecuador to maximise the results.

In the long term, within a digital world, we believe that the value of triennials is not in what is built on site, but in the message that is broadcast beyond geographic borders. In this way, the dissemination of ancestral techniques, living systems and materials from other latitudes are shown in a way in which, were it not for this type of cultural platform, could hardly be made visible on a large scale. This is an act in which the protagonist is not oneself, nor what our creativity can create, but rather how many more we can help through our collective creativity.

"Our question: Where is this resource most valuable, or where will it have the greatest impact? The answer was clear: we had to take it to Ecuador to maximise the results."

- Natura Futura

KOOZ The term “waste colonialism” was first coined in 1989 at the UN Basel Convention when African nations expressed concern about the dumping of hazardous waste by high GDP countries. Yet, when one sees images like those of Accra’s Kantamanto Market 30 years later, it seems as though little has been achieved. While BUZIGAHILL studio attempts to reorient waste and its narratives back to sources in the North, this cannot be a long-term solution: it is clear that stronger policies and infrastructures are necessary. What is the potential of initiatives like Stop Waste Colonialism?

BH The Or Foundation in Accra created stopwastecolonialism.org and are campaigning for an Extended Producer Responsibility Fund (EPR) to place accountability on the Global North for the clothing waste they produce. It’s quite simple: It’s a fee that fast fashion producers pay for every garment they produce, collected in their respective markets and distributed to communities and organisations in the Global South that have been managing fast fashion waste for decades. They — we — need to be compensated for our work and for the damage caused to our industries. It’s really common sense. A good start would be for clothing companies like Primark to disclose their production volumes so there is a general understanding of what our planet has to process on a global scale — but h&m, adidas, Marks & Spencers and their counterparts refuse to disclose their production volumes too. What are they hiding?

"They — we — need to be compensated for our work and for the damage caused to our industries. A good start would be for clothing companies like Primark to disclose their production volumes so there is a general understanding of what our planet has to process on a global scale."

- Bobby Kolade, founder of BUZIGAHILL

KOOZ Natura Futura, at your office, architecture is never intended as a self-contained act but rather as a tool, to empower communities and the territory. How does this define the type of projects you decide to undertake and the clients you chose to engage with?

NF It could be said that a “way of doing architecture” has been established within the studio, but we believe that the Ecuadorian territory is so diverse that thinking about a single project typology is not possible. We believe that the project typologies come from an intense and sensitive reading of the context. Thus, in some way, the streets, the people, the sounds and pre-existing things begin to subtly indicate the path to follow in the design process. The result is due to the context and the stimuli we receive when walking the streets of the territory.

"We believe that the project typologies come from an intense and sensitive reading of the context. Thus, in some way, the streets, the people, the sounds and pre-existing things begin to subtly indicate the path to follow in the design process."

- Natura Futura

On the other hand, we don't know if we choose the customers or if the customers choose us. But we believe that all collaboration of a social nature starts from a seed that does not contemplate any personal benefit, given that in the studio we manage self-financed model community projects two or three times a year; where we design small prototypes with a small budget. As time goes by, these seed projects begin to bear fruit when they reach the eyes of NGOs or private organisations interested in developing these prototypes on a larger impact scale. In this sense, each project is a constant give and take where everything begins and ends with the intention of helping the city, the community and the human being.

Bio

Founded by Bobby Kolade, BUZIGAHILL is a Kampala-based clothing brand that works between art, fashion and activism. For their first project series called RETURN TO SENDER, they redesign second-hand clothes and redistribute them to the Global North, where they were originally discarded before being shipped to Uganda. Kolade was born in Sudan to Nigerian-German parents and grew up between Kampala and Lagos. He holds a Master’s degree in Fashion Design from the Academy of Arts Berlin Weissensee and has worked at Maison Margiela and Balenciaga in Paris previously.

Natura Futura was founded by José Fernando Gómez Marmolejo in 2015 in Babahoyo, Ecuador. The studio has been awarded at the Quito Pan-American Biennial and held an exhibition at the Architecture Festival in Bali, Indonesia and Valparaíso. Lately, the studio has been awarded with three Quito Biennial awards in 2020, and the Viena´s Brick Award in 2022. In their work, they consider it vitally important to work with contextual architecture: interpreting the place as an implicit requirement to do things, without forgetting the human context of these projects, understanding the emotional part of its inhabitants, their traditions, their customs.

Federica Zambeletti is the founder and managing director of KoozArch. She is an architect, researcher and digital curator whose interests lie at the intersection between art, architecture and regenerative practices. In 2015 Federica founded KoozArch with the ambition of creating a space where to research, explore and discuss architecture beyond the limits of its built form. Parallel to her work at KoozArch, Federica is Architect at the architecture studio UNA and researcher at the non-profit agency for change UNLESS where she is project manager of the research "Antarctic Resolution". Federica is an Architectural Association School of Architecture in London alumni.