Exhibited within the context of “Mission Neighbourhood”, this year’s edition of the Oslo Architecture Triennale, Peter Cook’s exhibition “Ideas for Cities” presents a selection of visions for the city of Oslo and beyond, conceived and drafted over a period of six decades. Always envisioned as experimental architectures, and most of the time as buildable artefacts, the drawings unveil a sea of possible and intertwined relations, networks and systems which truly re-imagine and explore the very language and discipline of architecture. It was indeed an immense pleasure to be able to discuss such imaginative, entertaining, dynamic environments and the potential that these visions withhold for the way we could inhabit our contemporary and future cities.

KOOZ Titled “Ideas for Cities” this exhibition spans an entire career dedicated to the city as a bedrock of tectonic explorations. Specifically, a selection of these drawings lies at the intersection of propositions and speculations for the city of Oslo. What ideas on the history, current state and future of Oslo does the work offer to a visitor walking into the Old Munch Museum?

PETER COOK My experience with Oslo is fairly complex and started in the late 1960s when I did my first exhibition here, through to the 1980s when I was invited by Sverre Fehn to teach at the University of Oslo School of Architecture and Design, all the way up to today, as I continue to go and back forth and explore the city through a series of drawn propositions. In recent years my numerous visits to Malmo whilst teaching in Lund have also enabled me to start placing Oslo in respect to the rest of the Nordic scene.

This series of explorations, which punctuate the entrance to the Oslo Triennale exhibition, span from urban ideas as the “Oslo Eastern Patch” (2006) a suggestion for the Waterland areas of Oslo in which I envisioned a Canal Arcade and “skittle” like short stay dormitories, to Island city (2011-2012) an elaborate doodle which then morphed into the Island Community project (2022) where I suggest an alternative to locating 2000 people on yet another piece of arable land but, nonetheless, within the fully serviced environment of Skjaelholmene. At the scale of the single artefact, and as a means of challenging the low-rise typologies of the city, one proposition also picks up on the tradition around the use of electric light to develop three vertical towers. Taking the lantern as a starting point, this is then scaled up investigating the buildings as beacons for the city. For this project, I was also very concerned with colour and studied a series of envelopes which would break from the canonical stucco, brickwork or stone cladding, and drew on the characteristic colours of Norway’s landscape - which can be seen in certain functionalist architects and more evocatively within a series pf paintings exhibited at the National Gallery.

In Oslo everything begins and ends enabling an observer to study the city’s architecture in terms of typologies, symbolism and rhetoric very easily. Rather than developing in sways, as in most larger cities, here everything occurs in pockets.

Fundamentally I believe Oslo is a deeply Germanic city with a Norwegian overlay. It is a very picturesque small-scale city. If one observes the big housing schemes as well as developments as those of Grünerløkka, these are smaller than if they would have been constructed elsewhere. What is also quite unique is that all these projects have a very defined starting and ending point. In Oslo everything begins and ends enabling an observer to study the city’s architecture in terms of typologies, symbolism and rhetoric very easily. Rather than developing in sways, as in most larger cities, here everything occurs in pockets.

In recent years a lot of investment has gone into the realization of monumental objects which have been planted on the city’s waterfront with little or no attention to their interstitial spaces. A quick comparison between the shared spaces which lie in-between the barcode houses, the new library and the new Munch Museum and the older part of the city with its classical buildings as the old national theatre, the station and the old university buildings one soon realizes that these have not been shaped around the individual. This is, of course, with the exception of the new Opera of which I am very fond of as I think it is a brilliant idea to take the land up over the roof to create a public space for the city.

KOOZ What have been your greatest surprises and discoveries when observing cities worldwide throughout the past 60 years?

PC I think one of the biggest surprises was my encounter with the city of Houston. By that time, I had been to Los Angeles many times and, by comparison, Los Angeles - with its defined neighbourhoods and topography which functions as a marker in the city - almost appeared as a European city. Prompted by the students at Rice University, where I was teaching at the time, what I thought about Houston and shocked me about it was the sheer endlessness of the city. I thought that the only way to discuss the urban fabric was through the act of drawing.

My surprise with Houston lied with the notion of distance and the lack of identity of the city’s infinite neighbourhoods leading me to questions how one could massage that identity and rethink the notion of a guided transportation system. The project evolved into a whole city proposition which was articulated around a central freeway and extremely characteristic villages strategically positioned in relation to this central transportation artery. When thinking back to Oslo I believe the greatest challenge truly lies in the part of Grünerløkka, where the street as shared social space has been totally foregone. I believe that the development should have been more radical in a way, with more, dare I say, grand planning rather than relying on the occasional use of nature and trees here and there. The western part of the city, where there is the Palace, appears to be more resolved and working far better.

ERLEND BLAKSTAD HAFFNER Going back to the notion of pockets of the city and the different times when they were constructed and ideologies which shaped them, this part of Oslo is clearly the result of the boom of the city which has, however, unsuccessfully resulted in the shaping of a boulevard which is clearly at the wrong scale and does not relate to the city.

I am always very much interested in the pockets and in ensuring that these structures have been designed to include different scales to which the inhabitant can relate to. I am concerned with the creation of spaces where people can deviate from pre-established paths.

KOOZ This specific Triennale focuses on the scale of the neighbourhood and communities and offers ideas and solutions on how to structure safer and more enjoyable shared environments. What have been your experiences, as an architect, in shaping these kinds of spaces?

PC I believe that my success in designing for people largely stems from my training and necessity to always draw a person inside a section. Even when working at large scales, as for example with the University project in Vienna, I am always very much interested in the pockets and in ensuring that these structures have been designed to include different scales to which the inhabitant can relate to. I am concerned with the creation of spaces where people can deviate from pre-established paths, I am keen on the niches, the balconies, and the tunnels. The bigger the building the more I want to pick at it.

I am also interested in the transformation that buildings undertake and the diverse ways in which they can continue to be relevant and serve their neighbourhoods and communities. If one takes this specific building, which was originally designed to host the Munch paintings, it is fascinating to see how, thanks to the Oslo Triennale, it is being tested and activated as cultural laboratory and who knows what will come next.

"Veg House: Stage 5" by Peter Cook, 2001. ©Peter Cook

KOOZ You are an architect who shook the conventional notion of cities through the act of drawing as well as having operated within these through the insertion of spectacular yet pragmatic artefacts. How fundamental is the act of drawing as a tool for discovery and to challenge and re-invent the architectural status quo, both within the business of ideas and buildings?

PC The body of work presented at the Oslo Triennale exists at the intersection of inventive thinking, formalist thinking and observation. Nothing really falls out of the sky. I am very engaged in the act of looking at things, even the mundane.

If one goes back to Archigram and both the collective and the individual projects developed by myself, Warren Chalk, Dennis Compton, David Green, Ron Herron and Mark Webb, it is very easy to trace these back to the tangible experiences we were having back then. At the time we were, in fact, all working on prefabricated housing for Taylor Woodrow and in particular system-built housing in a site in Fulham, on a joint project we did with the Ministry of housing. We were cutting our teeth on social housing and, if I think back to my time as a student at the Architectural Association, our fourth year were asked to build Roehampton Alton West Housing scheme and we had to do a housing scheme based on LCC statutory requirements. Within many of the drawings of Archigram, what is humorous is that in one or two we included handrails and made sure that the escalator overruns were the correct length and that the toilets and their piping would work. That to me made it more valid as a wild proposition. It might look wild, but you could build it and the escalators would work and the pipe runs would work. I know what I would have to do if I were to build it.

The body of work presented at the Oslo Triennale exists at the intersection of inventive thinking, formalist thinking and observation. Nothing really falls out of the sky.

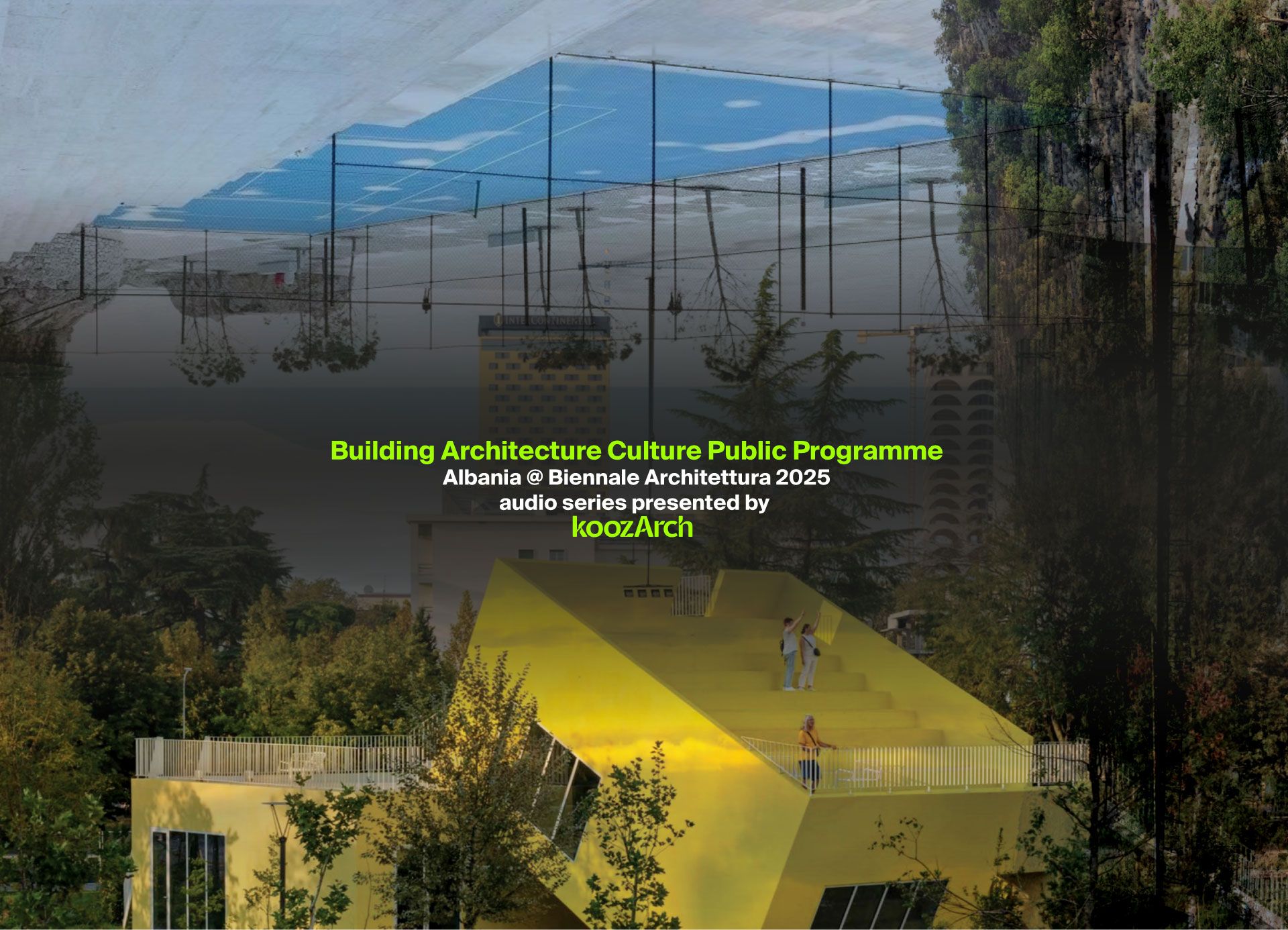

"The Plug-In City" by Peter Cook within the exhibition "Ideas for Cities", as seen within "Oslo Neighbourhood Lab" at the 8th Oslo Architecture Triennale. Credits: Are Carlsen

EBH I think this is also what transpires from the work exhibited here, although one might label it as utopian it is quite buildable.

PC I am interested in using drawings as a playground for the testing out of ideas. Sometimes these ideas bring forth real, straightforward propositions whilst others exist as hybrids in between proper proposals and speculative thoughts. In particular, I am interested in the exploration of the drawing as an exercise in the vocabulary of architecture. To date, I think we use an extremely narrow architectural vocabulary and have not really thought of the potential of materials and techniques and mixes of techniques beyond the brick wall, concrete wall and a bit of flimsy stuff. I am keen to expand our language beyond the artificial to include the natural and explore questions such as: what if the vegetal and the building are the same? Are there forms of vegetation that can be mixed into static structures? I trust that as designers we should go beyond and invent.

I am interested in using drawings as a playground for the testing out of ideas. Sometimes these ideas bring forth real, straightforward propositions whilst others exist as hybrids in between proper proposals and speculative thoughts.

KOOZ Today in addition to social sustainability, there is obviously an open discussion on the environmental sustainability of our built environment. The exhibition includes ground-breaking projects as the “Veg Village” which explores the ambiguous mixture of vegetation and architectural substance in a total mixture of enclosure vegetation and water (for hydroponics) and the co-existence of man-made built environment and natural landscape. To what extent does this body of work present ideas around the design of more environmentally friendly cities?

PC The greening of buildings has been around for a long time and to be totally honest, these propositions are more concerned with experimenting with ideas of what would happen if we put a hi-fi system in a tree rather than the ecological footprint of the building. How do you put a hi-fi system in a tree? What happens when you put a hi-fi system in the tree that becomes a chair? What happens if instead of having an enclosed kitchen, you would have it next to a bush? What happens if you start growing vines over the ceiling? What happens if some of the vines contain acoustic elements? What happens if you then start to introduce water? I am concerned with testing the limits of architecture and inhabitation.

The greening of buildings has been around for a long time and to be totally honest, these propositions are more concerned with experimenting with ideas of what would happen if we put a hi-fi system in a tree rather than the ecological footprint of the building.

"Tuscan Hilltop Town" by Peter Cook, 2019-20. ©Peter Cook

KOOZ Archigram was, of course, also a magazine. What role did this play as a vehicle for research and experimentation?

PC Archigram the magazine did include bits of what we would call research. It really existed as a point of encounter where each one of us would feed in his particular interest and collection of ideas and artefacts as, for example, was the case of the Pop-up issue where Ron heavily fed in a lot of his collection whilst Warren and I scavenged markets looking for old American comics which would have bit of architecture. A remarkable edition was Warren’s wartime editorial which challenged the 1950s and 1960s as years when the architecture scene came alive and shed a light on the forgotten period of the 1940s, revealing how numerous technologies developed for the war informed the discipline and practice of architecture. The magazine was also the medium through which I got to know Ron and Warren.

Bio

Sir Peter Cook graduated from Bournemouth Art College and Architectural Association, where he subsequently taught for 26 years. This was followed by the Professorship of Architecture at the Staedelschule, Frankfurt and then by his appointment as Bartlett Professor (and Chair) at the Bartlett, UCL. In a long career he has taught also at Harvard, Columbia, USC, Sci-Arc, Rice and elsewhere. His drawings are in the collections of MOMA New York, Centre Pompidou, DAM Frankfurt, FRAC Orleans, M+ Hong Kong and the V&A Museum London. His unbuilt projects such as Plug-in City and Way out West-Berlin are extensively published and he is the author of eight books, the latest of which is in the series ‘Lives in Architecture’, published by the Royal Institute of British Architects. He has built in Osaka, Berlin, Frankfurt, Madrid, the Kunsthaus in Graz (with Colin Fournier) and university buildings in Vienna, the Gold Coast and Bournemouth (as partner in CRAB Studio) He is a Royal Academician, member of the RIBA, Commandeur de l’Ordre des Arts et des Lettres, honorary Doctor of Technology at Lund University and Fellow of the Royal College of Art. As a member of ‘Archigram’ he was awarded the Royal Gold Medal of the RIBA in 2002. He is partner architect and Studio Director at CHAP.

Erlend Blakstad Haffner has his education from Bergen Architecture School, The Bartlett, UCL and The CASS, London Met. University. While still a student he founded the studio Fantastic Norway in 2004, which operated from a touring red caravan. In 2014 he established Blakstad Haffner Architects (BHA). He was project manager and responsible architect for the reconstruction of Utøya after the terrorist attack, creating the the memory and learning centre Hegnhuset, the conference facilities and and the new youth camp. BHA successfully operated until it merged into CHAP: Blakstad Haffner leads its business development and architectural innovation. Erlend is an optimistic architect with great interest for collaboration across disciplines – engaged in building design, development strategies, cooperative design, mobilisation processes, teaching and TV production. He has a special interest in design and planning of projects focussing on sensory experiences and the meetings between people. Haffner was recipient of the 2010 Iakov Chernikhov Prize, among other awards.

Federica Zambeletti is the founder and managing director of KoozArch. She is an architect, researcher and digital curator whose interests lie at the intersection between art, architecture and regenerative practices. In 2015 Federica founded KoozArch with the ambition of creating a space where to research, explore and discuss architecture beyond the limits of its built form. Parallel to her work at KoozArch, Federica is Architect at the architecture studio UNA and researcher at the non-profit agency for change UNLESS where she is project manager of the research "Antarctic Resolution". Federica is an Architectural Association School of Architecture in London alumni.