The essay accompanies the Nordic Pavilion at the 19th International Architecture Exhibition of La Biennale di Venezia, produced by the Architecture & Design Museum Helsinki. This extract accompanies Episode 07 “Hardbody: Industrial Muscle at the Nordic Pavilion” of our podcast Talks at the Venice Biennale, which you can tune into here.

Kaisa Karvinen, for Architecture & Design Museum Helsinki, Industry Muscle: Five Scores for Architecture

I.

When I started working on the concept of Industry Muscle in May 2024, architect Panu Savolainen asked me, “Did you ever think at any point that you might want to destroy the pavilion?” I laughed and told him yes, the thought had crossed my mind on a metaphorical level.

Industry Muscle: Five Scores for Architecture1 is a multidimensional artwork exhibited at the 19th International Architecture Exhibition of La Biennale di Venezia, in which the Nordic Pavilion, designed by architect Sverre Fehn and built between 1958 and 1962, is treated as representative of modernist ideals on several levels: its architecture, materials, textures and form. The desire to destroy is directed at the legacy of modernism, which shapes social power structures and influences our perception of the body, eventually impacting architectural design processes. In the context of this essay, I see destruction as a creative and reorganising practice whereby, rather than inflicting physical damage to the building, I deconstruct the mental framework that upholds the meaning and status of the pavilion in modern architecture.

"I see destruction as a creative and reorganising practice whereby, rather than inflicting physical damage to the building, I deconstruct the mental framework that upholds the meaning and status of the pavilion in modern architecture."

I have focussed on the influence of modernism on architecture, particularly as seen in the Nordic Pavilion; and on the petromodern2 mindset, shaped by oil, that was already present when Fehn designed the pavilion and continues to prevail in today’s world. I look at the ideologies that uphold so-called modernism and their impact, rather than a specific aesthetic or narrowly defined historical period. And I examine the idea of petromodernity, which Conway (2020, p. 48) tells us is “relatively new, having been developed by researchers in the field of energy humanities only in the past decade or so”. I show how the petromodern mindset has been bound up with the history of modern architecture, and how petromodernity in architectural practice has affected the way we understand the human being, body and gender.

I write from the perspective of a performance artist and a transmasculine person. I approach architecture as a space for staging the various sociopolitical norms that uphold a specific kind of sociocultural corporeality, whereby transcorporeality3 is subjected to pathologisation and differentiation. I use the trans body as a lens to examine architecture. I employ it as a crowbar-like tool to dismantle and reorganise the remains4 of modernist thinking for future architectural practice.

The trans body and its categorisation5 is a meta-architectural6 question that encompasses far more than just gender-neutral public toilets or changing rooms. In this essay, I argue that engaging with this meta-architectural work links the sociocultural normalisation of bodies inherent in modernism to ecological questions arising from the mass production of (petro)modernist architecture. Bodily norms are fossil norms, reinforced by architecture through the means of petromodernist production.

"The trans body and its categorisation is a meta-architectural question that encompasses far more than just gender-neutral public toilets or changing rooms."

My reflections on trans rights within the context of the ecological crisis arise from a sense of urgency. The violence and discrimination that trans people – and especially trans women – face are harsh realities demanding immediate attention – alongside and in relation to the multifaceted ecological catastrophe we are currently navigating.

II.

Transcorporeality as we understand it today emerged alongside modernist thought, even though gender variance has always existed. Trans identities are defined in relation to cisgender norms such as nuclear family, gendered expertise, behavioural expectations and normalised life course thinking. The concept of “trans” began to be used in the 1950s and 60s (Stryker, 2017, p. 36). The Western modernist gender binary7 system reduces transness to a category – and a disorder (Suess, 2014, p. 73-76). Through this framework, transness was merely a 20th-century idea for a 21st-century trend, erasing the reality that trans people have been profoundly embedded in Indigenous, religious and ethnic contexts throughout history. As cultural theorist C. Riley Snorton (2017) points out, Western representations of trans identity are shaped by racialised narratives where figures like Christine Jorgensen are the “good transsexual” while colonised gender-nonconforming bodies are erased (p. 141). Our understanding of the term is therefore based on the colonialist gender binary norm that these bodies transcend.

According to architecture historian Beatriz Colomina and architect Mark Wigley (2016), the modern designer has been like a doctor who nurtures and rebuilds the body and psyche. I think that architects, throughout modernism and still today, are comparable to doctors in trans clinics, defining human genders and emphasising their observation. Modern architecture obsessively maintains certain categorisations: clean/dirty, healthy/sick, normal/abnormal (Colomina & Wigley, 2016, pp. 107–121.) All these categories also reinforce gender categories. Examples of categorising architectural spaces include dressing rooms, hospitals and prisons, to name but a few.

"Normativity in design and aesthetic preferences translates into an ethos of neutrality, whereby groups such as people with disabilities and cultural minorities are marginalised."

The central figure of modernist architecture, Le Corbusier, was obsessed with his own body and this obsession caused him to be fascinated with the connections between health and architecture (Colomina & Wigley, 2016, p. 176). He also created the Modulor, an anthropomorphic scale of proportions, based on an idealised male human body supposed to represent the “universal man”. The word “obsession” falls short of describing the intense amount of self-reflection that trans individuals must engage in under the heteronormative, gender binary system whose reference point is the “universal” male body. Normativity in design and aesthetic preferences translates into an ethos of neutrality, whereby groups such as people with disabilities and cultural minorities are marginalised. In the words of lawyer and trans activist Dean Spade:

Critical trans politics requires an analysis of how the administration of gender norms impacts trans people’s lives and how administrative systems in general are sites of production and implementation or racism, xenophobia, sexism, transphobia, homophobia, and ableism under the guise of neutrality (Spade, 2011, p. 73).

The concept of neutrality in modernist architecture – also exemplified by the Nordic Pavilion – manifests through its emphasis on purity, achieved through luminosity, transparency and lightness, as well as through the separation of genders and a deliberate ideological detachment from fossil production, which paradoxically is precisely what enables this façade of neutrality. What is characteristic to modernism in general, in the production of both objects and bodies, is to obscure material origins, making things appear independent of natural resources, even though they are heavily reliant on them.

Let us suppose that modern architecture started out as a doctor whose mission was to maintain normative physical well-being. That doctor went on to become a psychoanalyst, upholding the categories of mental illness and health. Today, architecture is entangled with ecological collapse and the fragmentation of the modern conception of humanity, amid vast amounts of waste and the grime of modernist thought, in an obscenity of surplus inconsistent with the mould of the Modulor Man.

"Today, architecture is entangled with ecological collapse and the fragmentation of the modern conception of humanity, amid vast amounts of waste and the grime of modernist thought, in an obscenity of surplus inconsistent with the mould of the Modulor Man."

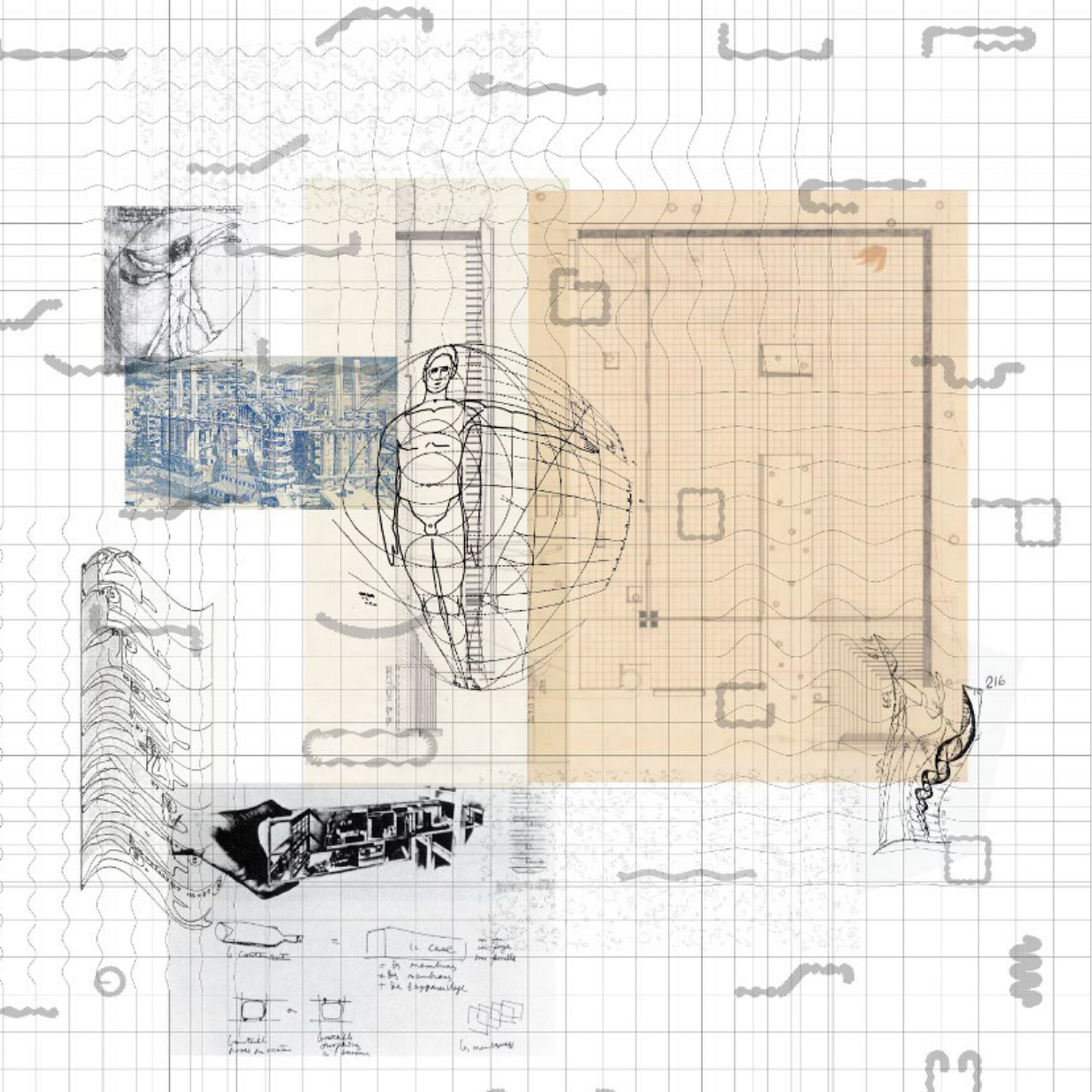

'Drawing A' extracted from 'Bodytopian Architecture': An essay written for 'Industry Muscle: Five Scores for Architecture'. An overview drawing of the written piece in graphic form. The plan and section of the Nordic Pavilion, as well as drawings of other notable Western concrete architectures, loom behind a regular grid, setting the stage for a modernist critique. The grid is disrupted by the distorted “ideal” bodies of da Vinci’s Vitruvian Man, Le Corbusier’sModulor Man, and a man from Architectural Graphic Standards. Familiar shapes of concrete rebar are made unrecognisable, shifting away from the grid in their own pattern.

Bio

Teo Ala-Ruona is an interdisciplinary artist based in Helsinki, working internationally within the expanded field of performance. Ala-Ruona’s work is strongly tied to theory, and he uses the performing body in his art as a reflective surface for the impacts of various societal, sociopolitical, and historical forms of power. Ala-Ruona’s work has recently been shown e.g. in Performa Biennial, New York; The Vilnius Biennial of Performance Art; The Finnish National Gallery Kiasma, Helsinki; and The Institute of Contemporary Arts in London. Ala-Ruona holds an MA in Art Education and an MA in Ecology and Contemporary Performance.

Notes

1Industry Muscle is created with a working group: A.L. Hu (essay dialogue partner); Teo Paaer (sculptural installation and spatial design); Tuukka Haapakorpi (sound design); Venla Helenius (video); Kiia Beilinson (graphic design); Even Minn (dramaturgy and score editing); and Ervin Latimer (costume design). Performers: Caroline Suinner, Romeo Roxman Gatt and Kid Kokko.

2Petromodernity as a concept emerged in academic and cultural discussions in the early 2010s. The term is used by a range of authors, who use it to signify “modern life based in the cheap energy systems made possible by oil” (Conway, 2020, p. 48).

3I aim to use the terms trans body and trans corporeality as intellectual mediums, while also recognising their connection to material experiences. Transcorporeality is a term I use to broadly refer to the interplay between the psychological, mental, conceptual, and material dimensions of a trans person’s experience of themselves. I am aware of Stacy Alaimo’s ecocritical approach to the word (Kuznetski & Alaimo, 2020), I use it with a slight distinction, with specific reference to transgender corporeality. For me, transcorporeality as a concept is broader than the trans body and can be approached as a theoretical tool for reflection. It invites anyone to explore and question their own experiences of embodiment and gender in relation to normative and binary gender conceptions. The trans body, on the other hand, refers to someone who embodies various facets or aspects of transcorporeality. The term “trans body” is more grounded in materiality, referring to the tangible presence of a trans body as it exists in the world, visible and verifiable in its movements and interactions.

When I use the word trans, I am referring to all trans people—that is, individuals whose gender does not align with the one assigned to them at birth. I use the term trans body with the understanding that trans bodies exist within different sociopolitical intersections and that these differences shape diverse struggles, with some trans people being more privileged than others. I also recognise that, as a white, able-bodied transmasculine person, my trans body is significantly more protected and less exposed to the threat of violence than, for example, the bodies of trans women, transfeminine people, and Black and disabled trans people. I use the term trans body as a synthesis of my own lived experience and in dialogue with other trans theorists. I acknowledge that I write from my own position, and therefore my perspective is always rooted in and emerging from my subjective experience—and is inevitably partial and incomplete.

4In this essay, I use the term remains to refer to surplus, abandoned or discarded things. My relationship with the word is both personal and political. I relate to it from the perspective of trans experience, and the trans body as a remnant of the production of the cisnormative body. The verb remain is strongly suggestive of survival and persistence, which I associate with the embodied experience of transness within the hegemonic structures that seek to destroy it. I use the term remains also to refer to the lingering influences of petromodernism that persist in our thinking, even after we have come to recognise the effects of petromodernist production on our environment, in climate change, for example. Lastly, I use the term to refer to architectural remains — ruins of buildings and leftover structures – and how we relate to these.

5I refer to categorisation as processes of thinking whereby things, phenomena, actions and people, as well as their inherent qualities, characteristics or traits are divided into intellectual compartments according to various pre-established categories.

6In this essay, the word meta-architectural refers to research, analysis, and thought that aims to examine the underlying thought patterns, historical, social and power processes influencing architectural thinking and work. I view architecture as inseparable from broader sociopolitical issues, including questions of gender, which are often dismissed in architectural discourse.

7The “gender binary” is used to describe the “system that classifies sex and gender into a pair of opposites, often imposed by culture, religion, or other societal pressures” (Kendall, 2023).