This conversation brings together members of O grupo inteiro, lumbung.space and lumbung.kios to explore the dynamics of collective work. With the former initiatives embedded in Brazil’s socio-political landscape and and the latter emerging from documenta 15, their dialogue unpacks the challenges and possibilities of building – and unbuilding – institutions, reclaiming agency, and sustaining long-term collaborations beyond given frameworks.

This conversation is part of our partnership with the Nieuwe Instituut. A series of 10 contributions with 10 former fellows to celebrate the 10-year anniversary of the Research Fellowship Programme.

FEDERICA ZAMBELETTI / KOOZ Before diving into institutional practices, it might be helpful to understand who you are and how you approach your work. Could you share a bit about your background — where you're based, your journey in your practice, and any longstanding relationships that have shaped your work?

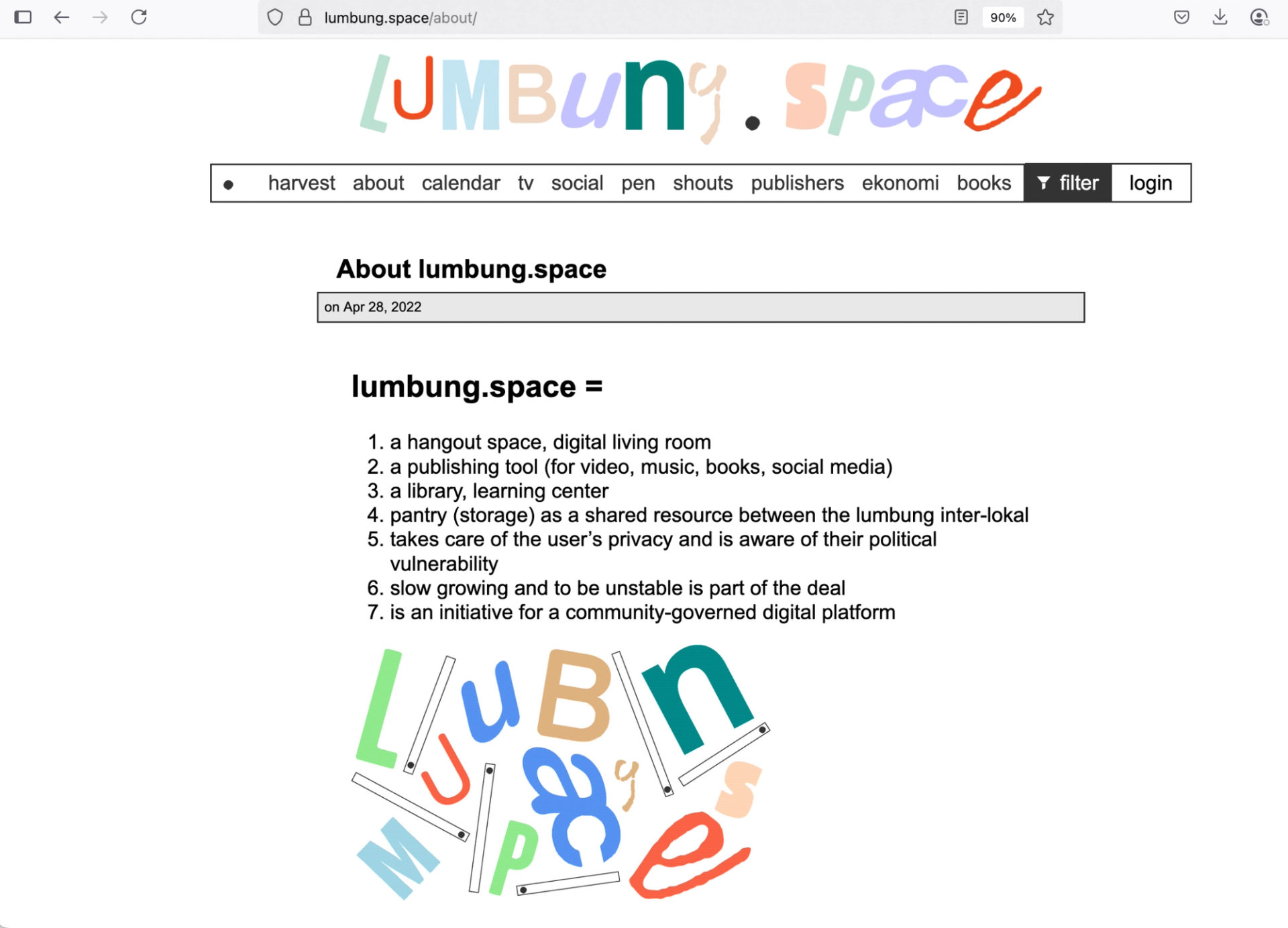

REINAART VANHOEI’m here representing lumbung.space, the internet platform we’ve been working to bring to life before, during, and after documenta 15, in 2022. It’s not just a tool — it’s an architectural infrastructure, a work in itself. And I’m only one of the many voices involved, so whatever I say is just a fragment among many perspectives. We operate within an understanding of multiple angles, but they need to be voiced as part of the conversation.

KRISTA JANTOWSKISimilar to reinaart, I am just one of many voices within lumbung.kios (N.B. kios is Indonesian for kiosk, while lumbung means rice barn — lumbung was one of the key words for developing documenta fifteen referring to ‘shared resources’) I joined after — or maybe during — documenta 15, right in the midst of it. My background comes from running a shop for seven years, and through that, I had ongoing conversations with reinaart about what is a shop is, what is a bookshop, what transactions mean, and how we can remain playful in administrative practices. If we allow playfulness at the front end, why shouldn’t we bring that same approach to the back end?

"How we can remain playful in administrative practices. If we allow playfulness at the front end, why shouldn’t we bring that same approach to the back end?"

- Krista Jantowski

This led to different ways of rethinking the often invisible or mundane work that keeps structures running. My entry into kios came from that perspective. Within the collective, members have vastly different institutional connections, which makes each relationship to the institution unique. My own practice and engagement with institutions differ from others in kios, shaping the ways I interact within this shared framework.

LIGIA NOBRETogether with Vitor, Carol Tonetti and Cláudio Bueno, we form O Grupo Inteiro. We started in 2014 as a shared practice, bringing together different backgrounds. I come from architecture and curatorial practice, while Vitor comes from art and design, like both Carol and Cláudio.

Personally, I shifted toward working with non-profit institutions early on. In the 2000s, I founded the first residency program in São Paulo, focusing on aesthetic and political issues both locally and internationally. Over the years, I’ve worked on different projects across various cities. When we came together in 2014, we realised that this platform could grow into a space for sharing, thinking and collaborating across different projects.

We’ve continued working individually on distinct issues, but O grupo inteiro functions as a shared platform for research and institutional collaborations. While based in São Paulo, our work takes shape in various contexts. Over the past ten years, our efforts have centred around project-based research, with cycles occurring every two years. One such initiative originated from a grant proposal tied to a project Vitor was developing with another artist, Enrico Rocha. We joined forces to work on it, specifically in Northeast Brazil, and that experience opened up critical discussions that we’re eager to explore further.

"O grupo inteiro functions as a shared platform for research and institutional collaborations."

- Ligia Nobre

VITOR CESARI studied architecture, but my work has shifted more toward art and graphic design. Right now, we’re collaborating within O Grupo Inteiro, but I also have an independent graphic design practice, primarily working with artists, curators, and art institutions. It’s about experimenting — trying to push boundaries within design and artistic collaboration.

"It’s about experimenting – trying to push boundaries within design and artistic collaboration."

- Vitor Cesar

KOOZBuilding on what you’ve just discussed — the different realities and networks coming together — how do you see the potential of organising and making through these collectivised networks? Given that each of you brings an individual perspective within the group, how does this structure shape collaboration?

LNVitor and I had been sharing thoughts beforehand, and for us, collectivity is key — it opens conversations and strengthens individual practices. But beyond that, it creates possibilities for organising around shared concerns, navigating common structures, and engaging with the complexities of collective work.

"Collectivity is key – it opens conversations and strengthens individual practices. But beyond that, it creates possibilities for organising around shared concerns, navigating common structures, and engaging with the complexities of collective work."

- Ligia Nobre

It’s not simply about fitting into predefined frameworks but about amplifying voices while respecting their distinctive aspects. Naturally, conflicts arise and interests differ, even at the micro scale. Yet by opening up to multiple perspectives, we find ways to reinforce and deepen our work. I think that’s the essence of it.

VCInstitutional practice is particularly complex right now in Brazil, especially within the art world. Things are shifting rapidly — institutions are becoming increasingly tied to market forces and financial concerns, which is quite different from how they operated ten or fifteen years ago. The challenge here is that institutions are still in formation; they are not fully established, which creates a contradictory dynamic. On one hand, we need to build them, but at the same time, we have to critique them — even though they are not yet fully realised. It’s an ambiguous position; we find ourselves questioning how to engage with something that is still in flux, still unstable.

" Institutional practice is particularly complex right now in Brazil, especially within the art world. Things are shifting rapidly – institutions are becoming increasingly tied to market forces and financial concerns."

- Vitor Cesar

When we’re invited to take part in exhibitions or projects, we try to push beyond conventional approaches. Instead of simply presenting work, we initiate discussions about the structures behind these projects — how they function, how finances are managed, and how institutional frameworks affect artistic practice. Our goal is not just to participate but to understand what is happening within institutions and explore ways to collaborate meaningfully.

One example is a project we did with Casa do Povo in São Paulo. They invited us to develop their library, and rather than treating it as a straightforward task, we approached it as a process of collective learning. We worked with their partners, finding ways to build the library while engaging people in the making process itself. The woodworkers involved were not just executing a design but learning as they built — turning the act of construction into a pedagogical experience.

RVIf I understand correctly, you're saying that the library isn't just something placed within an institution — it’s a practice in itself. The act of building the library becomes part of the learning, exchange, and shared access, rather than just a resource to be activated once it’s finished. So, in this approach, the people constructing the library could also contribute in different ways — bringing in books, creating books, or even weaving their communities into the space. The making of the library is just as significant as its final form.

LN We always try to engage with the process itself — to problematise it — while working within precarious conditions. As Vitor mentioned, ambiguity is part of what we navigate. Destruction is easy, so the question becomes: how do we weave in ways that reinforce existing structures while remaining fully aware of their contradictions?

"Destruction is easy, so the question becomes: how do we weave in ways that reinforce existing structures while remaining fully aware of their contradictions?"

- Ligia Nobre

That example, for instance, was about listening — engaging with the communities, the craftsmanship, the books, the knowledge, and the collectives already embedded within the institution. We immersed ourselves in their modes of operation, their practices, their questions, seeking ways to interweave approaches that not only expose issues but also build something in the process.

It’s fragile. Right now, we are hostage to the market — not just in Brazil, but globally. I see it in Europe as well. The landscape is shifting toward extremes, particularly the far right, and the systems we operate within today feel vastly different from even a decade ago. This means we are navigating an entirely new ecology — one that is transforming at an unsettling pace.

KOOZHow does lumbung operate both as a collective entity and as two distinct realities — the lumbung.space platform and the kiosk? What is the power of collectivising as a whole while also maintaining these two separate yet interconnected realms within the project?

KJI was reflecting on the Research Fellowship Programme and its potential — how it provided a framework for organising and reconnecting. Institutions can offer occasions for networks to gather again, and I think that was one of the simple yet important aspects of the fellowship. It created an opportunity for us to respond, react, and re-enter conversations with one another.

While we all have practices tied to lumbung.kios or lumbung.space, the challenge is in bringing these knowledges together,;understanding where we stand collectively, and recognising what the exchange can offer. It’s about sustaining dialogue — staying in touch and remaining aware of how individual practices evolve.

At the same time, I see what you're saying, and I’m curious about how this dynamic plays out in your work. Institutions often operate with a certain logic — one that exists but is not explicitly articulated. In these negotiations between collective practice and institutional concerns, there’s a tension not just in how to engage but in how to make the institution itself visible.

It’s not always about meeting the institution head-on; sometimes, it’s about finding language, creating opportunities to respond, and making space for dialogue. Often in these collaborations, unspoken structures shape interactions to the point where it’s difficult to grasp how an institution moves — let alone find ways to respond or move alongside it.

"It’s not always about meeting the institution head-on; sometimes, it’s about finding language, creating opportunities to respond, and making space for dialogue."

- Krista Jantowski

RVMany of us have operated in contexts outside of traditional art institutions — without those infrastructures — yet we have continued to create work despite their absences. I come from the perspective of someone who has never been involved in directing an institution, although I have worked within them as an employee or collaborator. That position makes a difference — it’s easier to critique institutions from the outside, but when you’re inside, you see the complexities and constraints they face. One challenge is that institutions are often too occupied or structurally hindered to carve out space for what they cannot do. I believe this is a crucial aspect of institutional transformation — finding ways to create room for new practices that go beyond their current capacities. Institutions should not be seen as adversaries but as potential allies, in abstract and literal ways. The question then becomes: how do we take steps forward, build alliances, and reshape institutional frameworks?

"It’s easier to critique institutions from the outside, but when you’re inside, you see the complexities and constraints they face. The question then becomes: how do we take steps forward, build alliances, and reshape institutional frameworks?"

- Reinaart Vanhoe

With lumbung.space, we faced this tension firsthand during documenta 15. The institution saw digital infrastructure as merely a tool, rather than recognising it as an architectural system that could be fully embedded in its structure. Often, institutions allow artists to contribute to programming but not to the architecture itself — they enable reactive participation but rarely support proactive engagement.

The library is a good example of an alternative approach. A library is not just a project; it is an integral part of a building, embedded in the long-term programming rather than treated as an isolated initiative. In this sense, the work is done despite the institution’s limitations. However, when collaboration happens, it allows for more meaningful steps, expanded exchanges, and the potential to reshape practices at different scales.

Another important aspect, which may or may not be directly connected, is resource-sharing. This should not be framed as artists versus institutions but as a process where both sides create pathways for redistributing resources. Institutions and artists alike should pass on access — not just within their own circles but to what I call the “first public,” the people in local and distant communities who engage with the work in its immediate surroundings.

lumbung.space (2024). ©: lumbung.space.

KOOZYou bring up a compelling point, reinaart — the idea of thinking about architecture beyond the building and institutions beyond their physical form, instead engaging with them at the level of infrastructure. How do you navigate the tension between local impact and working as part of a global collective network, connecting different realities? How do you reconcile these two distinct scales and approaches in your practice?

RVFor us — speaking from my perspective — lumbung.space and kios are still evolving. We haven’t fully arrived at the global infrastructure we aim for. The challenge lies in defining what a digital infrastructure is and how to use it critically. It’s easy to rely on existing tools like Google, but questioning them comes at a cost. Take African Stream, an African media channel — they used Google’s nonprofit infrastructure but were erased entirely when their content became too critical of certain global powers. They lost everything.

"The challenge lies in defining what a digital infrastructure is and how to use it critically. It’s easy to rely on existing tools like Google, but questioning them comes at a cost."

- Reinaart Vanhoe

It’s simple to use familiar platforms, but building our own infrastructure within lumbung.space requires something different — our own tools, maintained with care, knowledge, and sustained commitment on a daily and weekly basis. That’s why it’s lumbung.space, not lumbung.art — it’s about creating space that can meaningfully connect different localities, allowing them to inform each other on how to shape the platform in a more material, embedded way.

We’re still navigating this struggle. lumbung.kios, too, is a work in progress — a place for practicing, testing, and refining approaches. I don’t see that as a failure; rather, I think of it as a potential space — something in preparation, ready to be activated when urgency calls for it.

Right now, we are not at the stage where different spaces and localities can fully integrate and form a network. This isn’t just about artistic infrastructure — it’s tied to broader institutional conditions and the capitalist systems we work within, which obstruct progress. Acknowledging this reality rather than resisting it outright might actually be a healthier stance for now.

KJIn terms of operating kios, there’s a fundamental distinction — we’re a collection of local practices, deeply interconnected yet shaped by individual conditions. We rely on one another in very practical ways. For example, right now, we have a small kios in Utrecht with our partner at Casco (Casco Art Institute: Working for the Commons). Previously, a large part of our stock was stored in someone’s studio in Rotterdam, and access depended on when they were present.

So, imagining kios as something with a truly global dimension feels like a kind of fiction. We are simply people working locally, talking amongst ourselves, exchanging knowledge through direct connections. The global aspect emerges as an abstract notion — through the platforms where we meet, the systems we rely upon. It becomes clear when deciding how to communicate: in the end, we meet on Zoom because rival applications like Jitsi don't always function smoothly. Realisation like that makes us aware of how much we are bound to global structures, even as our work remains grounded in local realities.

Rather than seeing global and local as opposing forces, we operate in an integrated way. We are local practitioners conversing with one another, navigating overlaps and differences, making decisions based on shared needs rather than a rigid binary framework.

RVTo add to that — unlike O grupo inteiro, lumbung is more of an abstraction of real practices rather than a clearly defined entity. It exists across distributed exercises, whether lumbung.land, lumbung.radio, or lumbung.press. The approach is about platforming — creating a dispersed network rather than focusing on a single, concrete project.

"The approach is about platforming – creating a dispersed network rather than focusing on a single, concrete project."

- Reinaart Vanhoe

lumbung.kios is mostly made up of real practitioners. Take Elaine W Ho, for example — she has her own method of distributing books from Hong Kong, moving them through personal networks rather than relying on FedEx or DHL. A reference point — not ours, but relevant — is the Feral Trade shop in London: a project that started in 2003 as a grocery business and long-range economic experiment, where all transactions occur through social networks, hand to hand. The question for us becomes: how do we achieve something similar, but as a fully distributed platform?

There’s no fixed solution, no formal subsidy or funding structure tied to a singular project with a set number of participants. We move slowly, experimenting, using occasions like the Nieuwe Instituut Research Fellowship as a space to shape, test, and refine the work.

KOOZO grupo inteiro takes a hyper-local approach to institutional practice, working within specific sites to shape decolonial structures. Can you share more about the project itself and how its themes — while rooted in particular contexts — might translate globally? How do its ideas remain adaptable to different histories and conditions?

VCThe Northeast region of Brazil is marked by drought — its landscape differs entirely from the south, vegetation-filled image often associated with the country. Moreover, the perception within Brazil frames the region as inherently poor. In reality, that idea was shaped by state policies rather than by the land itself. Infrastructure and large-scale capital bypassed the region, reinforcing the narrative of scarcity.

One key institution — the National Department for Drought Construction — embodies this contradiction. How can one be against drought? It’s a natural condition, not something to fight. The department has carried out various projects over time, but has faced many reports of corruption. Our research, which began with the Research Fellowship Programme, sought to reconsider these institutional frameworks and explore new alliances to reframe this narrative.

The fellowship was instrumental — it allowed us to visit these places with more people, meet local communities, and expand our network organically. We built connections through trust, where one introduction led to another. Following that, we participated in another fellowship, and now, we’re working on a small publication that brings together perspectives: someone deeply embedded in the local environment, observing nature firsthand, alongside an engineer thinking structurally about the region.

Drought doesn’t announce its arrival. Unlike storms, which start and stop visibly, drought unfolds over months or years, often imperceptibly at first. In many ways, our work mirrors that process — a poetic image of slow formation and renewal. We operate within cycles: the first fellowship helped establish relationships, a period of informal engagement followed, and the second fellowship reactivated these connections. The alliances we’re forming are rooted in time — we’re building something long-term, even without certainty about where it will lead.

"The alliances we’re forming are rooted in time – we’re building something long-term, even without certainty about where it will lead."

- Vitor Cesar

Looking ahead, our next step is to work with the people we’ve met. They bring diverse perspectives; for example, Neto Camorim — on whom, more later — often makes me rethink institutions. He revisits a historically significant site of resistance in Brazil each year and is now purchasing a small plot of land where he hopes to create a space for others to gather. He’s not from the art world, yet his idea looks almost like a residency. His initiative raises fundamental questions about institutions, access, and how we engage with communities.

LNThe project is both a practice and a process, shaped by the very institution it critiques — a colonial entity from the 1930s that still exists today. As Vitor mentioned, we’ve appropriated its name and redefined it in ways that bring it closer to the territory, shifting its meaning and function.

When Vitor and Enrico began developing the project, and O grupo inteiro joined in, we started thinking of it as a meta-institution — one that actively engages with these systemic issues rather than merely replicating them. The pandemic was a critical moment for this, politically and socially. It forced us to confront internal challenges, including navigating failure and questioning what would be “enough.” Unlike a conventional institution, we never set out to build something fixed — it unfolded as a process, much like the biome itself.

As Vitor described, the region’s droughts and moments of rain continuously reshape the landscape. Our work follows a similar rhythm — it doesn’t mimic the environment but flows with it, adapting and evolving. Bringing in funding sources, whether from Brazil or institutions like the Nieuwe Instituut, has allowed us to deepen these processes, though uncertainty remains central to our approach.

At its core, the work is about deep listening and micro-scale actions — small, local engagements that carry significant weight over time. Unlike lumbung, our structure isn’t built as a visible platform but rather as an invisible network that gains visibility at different moments.

"At its core, the work is about deep listening and micro-scale actions - small, local engagements that carry significant weight over time."

- Ligia Nobre

This requires careful pacing. Operating from São Paulo — a more Westernised urban centre — demands that we, as allies, hold space for slower, nonlinear forms of engagement. It’s about timing, allowing processes to unfold organically, and strategically materialising them in ways that make sense within their context.

KOOZWhat alternative knowledge systems do you draw upon to engage with the territory differently? What frameworks — whether indigenous, ecological, social, or otherwise — inform your approach to reimagining the space?

VCThere’s a wealth of local knowledge, but we’re careful not to frame it as folkloric or reduce it to a simplistic category. Instead, we focus on how different knowledge systems intersect and inform one another.

Take weather prediction, for example. Meteorologists use scientific models, but local communities — those who have observed the land for generations — often have an intuitive understanding of climate shifts. While we still rely on science, the question is: how can these different perspectives work together? How can everyone learn from one another?

This is central to our approach: engaging with people to better understand these varied knowledge resources. Neto Camorim and Ailton Brasil — two history teachers working with teenagers — are good examples. They root their teachings in the land, ensuring students engage with their territory in tangible ways. As a result, a new generation in the city is actively shaping institutional structures — some now hold positions in local government, influencing policy and decision-making.

Neto and Ailton aren't connected to the art world, yet their practice carries elements of performance. Every year, they travel to Canudos — the site of an historic uprising — continuously gathering new insights about its history. They convince others to join them; each year, 40 or 50 people rent a bus and make the journey together.

This initiative is entirely self-organised, funded by the participants, and sustained by their collective commitment. It’s a model that makes me reflect on how institutions function and how grassroots efforts can influence state structures. There’s something profound in how knowledge is passed along through action, experience, and shared practice.

KOOZLumbung operates at the intersection of knowledge-sharing and platforming. Beyond the knowledges it gathers, what specific tools have enabled the platform’s formation — first at documenta 15, and then as a project that continues to evolve? How have these tools contributed to its ongoing development and sustainability?

RVThat’s something I still find myself questioning — whether lumbung.space is a tool or a space. Right now, we’re about five people, and much of its visible structure still is in relation to documenta fifteen itself. Of course we’ve moved beyond it but in some translations of usage of tools and added content we are still not that much updated . Now, the focus is on our practices and not on documenta fifteen, so now we’re in the process of deciding which tools to keep and which ones to let go. At one point, I thought we might wipe everything and restart — but once a tool exists, it carries responsibilities, expectations, and unforeseen dependencies. That makes it difficult to simply erase and start over.

There’s the storage system — a cloud-based service housed externally rather than on our own servers. That raises the question: do we continue renting server space, or do we transition to a decentralised model where individuals maintain servers within their own communities? That would require technical expertise, either through educating ourselves or engaging those already skilled in the process.

Our meeting space — we call it nongkrong — is a kind of digital café; it’s an informal gathering point rooted in its Indonesian name. There’s books.lumbung.space, where users can upload and curate publications, along with collaborative writing tools that function like Google Docs but within our own infrastructure. Then there’s tv.lumbung, which operates on PeerTube, an open-source video tool.

Currently, we have around ten tools, but many are only actively used by one or two collectives. Ideally, we’d reduce and rebuild — perhaps prioritising nonkrong, the bookstore/library, and tv.lumbung. But at the same time, tools like storage remain essential, particularly for lumbung.press and Documenta’s non-institutional archive, which still resides within our system.

Adding to the challenge is the fact that the working group operates on a voluntary basis — only technical maintenance is compensated. We want to shift that structure so those handling upkeep are paid fairly, while others contribute in different ways.

The Research Fellowship Programme gave us space to reassess whether lumbung.space still holds relevance. It forced us to ask: should we continue? In the end, responsibility kept us moving forward. If I speak personally, I envision lumbung.space as a welcoming room — a space to meet, exchange, and activate tools in meaningful ways. Similar to how a library isn’t just a storage system for books but a space where knowledge is processed collectively.

"I envision lumbung.space as a welcoming room – a space to meet, exchange, and activate tools in meaningful ways."

- Reinaart Vanhoe

We have a meeting tomorrow to reframe and refresh — because 2025 brings a shift. documenta is reverting to its traditional model, returning to "real art" rather than what some might call “bullshit art” — implying our kind of practice. So the question is: how do we reposition ourselves? What can we offer back to those who have shaped and sustained lumbung.space?

Lumbung kios, 2024. © lumbung.kios.

KOOZAre there specific references that have shaped your way of operating and the development of your initiatives?

KJI don’t have a concrete reference, but I think institutions sometimes create fleeting moments of attunement — small, mundane gestures where something clicks, where a gathering feels unexpectedly productive, where there’s a real sense of being welcomed. And, of course, institutions are made up of people, and you can often feel the presence of someone working within them who helps facilitate these moments.

What stands out to me is when institutions step back slightly — when they allow themselves to be hosted by something else, rather than always imposing their own structure. In those instances, there’s a different kind of openness, an alignment with what’s directly present rather than what’s dictated top-down. These instances may not transform an institution outright, but they show glimpses of how engagement can shift — if only for a moment.

RVI think it’s important — not in a negative sense, but as a reality — to accept that things are always somewhat broken, that loss is inevitable. Those words might sound pessimistic, but really, embracing imperfection allows action to happen. I often think of Jatiwangi Art Factory. Their approach acknowledges defeat within the international garment industry — the destruction of landscapes and livelihoods by corporate forces. They recognise that fighting these giants means losing in a conventional sense, but they still take action. For example, they worked with Taiwanese investors to negotiate land contracts that protect the environment, even amid relentless construction and infrastructural damage. Despite the scale of loss, there are still interventions to be made.

One key lesson from this — and from documenta 15 — is the power of being with the many. The 2022 edition of documenta invited artists(collectives) to involve their broader network. ruangrupa opted for one shared articulation instead of installing 100 solo shows. They as well restrained from using country names the artists came from. The mainstream press outlets had difficulty digesting the absence of identifiable actors and lacked language to write about collaborative practice and its strengths and qualities. So the press reduced the distributed participation to a gimmick, portraying it as simply thousands of artists gathering. But the depth of the engagement, the actual practice of collaboration, wasn’t fully captured. The act of being many isn’t about declaring definitions — it’s about experimenting, trying things out, pushing beyond boundaries.

If Ligia does something and someone asks me about it, I might not have a definitive answer — but that’s the nature of collective work. Trust operates within the space of uncertainty. The answer, if there is one, is to be with the many — to lean into collaboration, even when the outcomes aren’t perfectly defined.

"Trust operates within the space of uncertainty. The answer is to be with the many – to lean into collaboration, even when the outcomes aren’t perfectly defined."

- Reinaart Vanhoe

KOOZGiven O grupo inteiro’s direct response to an institution moving in the opposite direction, how does it function as a safe haven within the Brazilian institutional framework? What potential does it hold for catalysing other realities across the country — forming an infrastructure of practices that operate outside or even against traditional institutions?

LNInstituting processes — despite their contradictions — remains essential. As you pointed out at the beginning, counter-institutional practices don’t exist in isolation; they interact with institutions in layered, complex ways. As lumbung emphasised, institutions are ultimately made up of people, shaped by different moments and engagements.

O grupo inteiro joined the long-term project that Vitor had initiated, and within that, we’ve worked in a fluid, relational way — strengthening ourselves through friendship, shared methods, and process-driven collaboration.

Right now, I find myself questioning what comes next for our group. We’ve dispersed into different activities, each of us navigating distinct directions. I recently reconnected through new funding to help with a publication that builds on the post-Nieuwe Instituut phase. As Vitor mentioned, minor gestures from earlier moments are now materialising through this work.

Ultimately, it comes down to trust — trusting the relationships we’ve built, maintaining those connections, and recognising the evolving nature of these alliances. Processes will shift; sometimes they’ll become sites of resistance, sometimes spaces of solidarity. At this moment, it feels urgent to avoid fragmentation, to counter the forces of compartmentalisation and individualisation that threaten collective work. We have to stay attentive to deeper relationships — to trust them, maintain them, and care for them. That is what will sustain these practices and allow them to evolve in meaningful ways.

VCI really appreciated what Reinaart said about being with many — I couldn’t agree more. And I also relate to the idea that while we cannot directly fight against capital, there’s room to maneuver within it, creating spaces for action in between.

As for the idea of a "safe haven," I’m not sure if that’s the right term for what we offer. When institutions invite us to collaborate, we sometimes become a challenge for them — not simply solving problems but allowing problems to emerge, making visible tensions that are usually left unspoken. In that sense, our presence in an institutional project isn’t just about fulfilling a conventional role; it’s about pushing for openness — questioning budgets, architecture, context, and engagement.

"Our presence in an institutional project isn’t just about fulfilling a conventional role; it’s about pushing for openness – questioning budgets, architecture, context, and engagement."

- Vitor Cesar

The reason this works is precisely because we are not just a single entity — we are many. When invited as O grupo inteiro, we expand the circle, inviting more people into the conversation. Though our core group consists of four members, we frequently bring in others, extending the dialogue and sharing the space. This creates a dynamic where invitations multiply, rather than remain static.

RVThree key ideas come to mind. First, sharing the difficulties of practice — not just our projects but the doubts, the uncertainties, the questions we wrestle with. Is this art? Is this architecture? Are we in the right field? We often present our work in ways that suggest clarity, but in reality, everyone walks away with lingering doubts. And that’s the practice itself — continuing, questioning, moving between jobs and projects. The real value lies in talking with others, reassuring one another, and exchanging energy through mutual support.

Secondly, the notion of social practice: I’ve moved away from thinking of it as a distinct category. Social architecture, social art — ultimately, all art is social. It’s not a niche; it’s the mainstream. It’s about positioning — whether as an artist, architect, designer, or educator — entering the space as a person, engaging through practice rather than definition.

Lastly, the idea of production chains — something relevant to both lumbung.space and lumbung.kios. Institutions need to understand that social practice is not a side project but rather a fundamental way of working. If they truly want the efforts to be mainstream rather than a symbolic gesture, it must be integrated into how resources are allocated, how budgets are structured, and how collaboration unfolds. It’s not about rejecting institutions outright but instead about asking: how do we play this out?

"Institutions need to understand that social practice is not a side project but rather a fundamental way of working."

- Reinaart Vanhoe

About

lumbung.space and lumbung kios conspire in a collaborative effort towards networked sustainability. They seek to develop digital tools and financial systems that counter extractive frameworks and instead emphasise entangled ways of working while navigating differences in access, distribution and forms of making public. Initially developed during documenta fifteen, lumbung.space is a platform that offers a set of (online) services, expanding on and collectivising a broad range of artistic and design practices. lumbung kios is an international network experimenting with the structure of a shop to raise and redistribute financial income through the sales of goods produced by and for the lumbung members, lumbung artists, and their local ekosistems, using instances of exchange as opportunity or review.

O grupo inteiro works in the fields of art, design, education, architecture and technology. Founded in Sao Paulo, Brazil, in 2014 by Carol Tonetti, Cláudio Bueno, Ligia Nobre and Vitor Cesar, its proposals emphasise spatial dynamics, conviviality, engagement with the body, and research into social and environmental issues. The group has collaborated with national and international institutions such as MASP, MAM-SP, São Paulo Biennial, Casa do Povo, Sesc (Brazil), Central Saint Martins/UAL (London), Nieuwe Instituut (Netherlands), Pro-Helvetia/FAR° (Switzerland), and the University of California, Santa Cruz – IAS / Visualizing Abolition (USA).

Bio

Federica Zambeletti is the founder and managing director of KoozArch. She is an architect, researcher and digital curator whose interests lie at the intersection between art, architecture and regenerative practices. In 2015 Federica founded KoozArch with the ambition of creating a space where to research, explore and discuss architecture beyond the limits of its built form. Prior to dedicating her full attention to KoozArch, Federica collaborated with the architecture studio and non-profit agency for change UNA/UNLESS working on numerous cultural projects and the research of "Antarctic Resolution". Federica is an Architectural Association School of Architecture in London alumni.