⾃梳 Zì Shū (Self-Combed), the title of the project, comes from an old Chinese ritual of braiding one’s hair, was once an act of autonomy and self-determination in Chinese female culture, a symbol of freedom from forced marriage and enslavement in family life. The last generation of self-combed women has disappeared but semblable groups have emerged nowadays. The single-women community in Taolin village, Beijing, is a co-living group practising land art as the dominant daily task. Land art here has emerged as a new ritual, intertwining with everyday domestic life, the ritual has redefined an alternative way for singlehood living.

The project forms a new community for single women, a community where everyday ritual is not defined by the norm but the shifting water. It’s a home for 130 over-30s women who no longer see marriage as life necessities. As well as the daytime assembly place for more females, here they decide how to spend their daily lives for creative cooking, ikebana, land art, etc. To better embrace the water condition, the project chooses to sit at a constantly changing shallow in the city of Chongqing, China, where the water level changes drastically during the year that could create various relationship between building and water. The shifting water brings uncertainty and temporality to the space that becomes ingredients to foster new series of rituals and encourage an autonomous way of living.

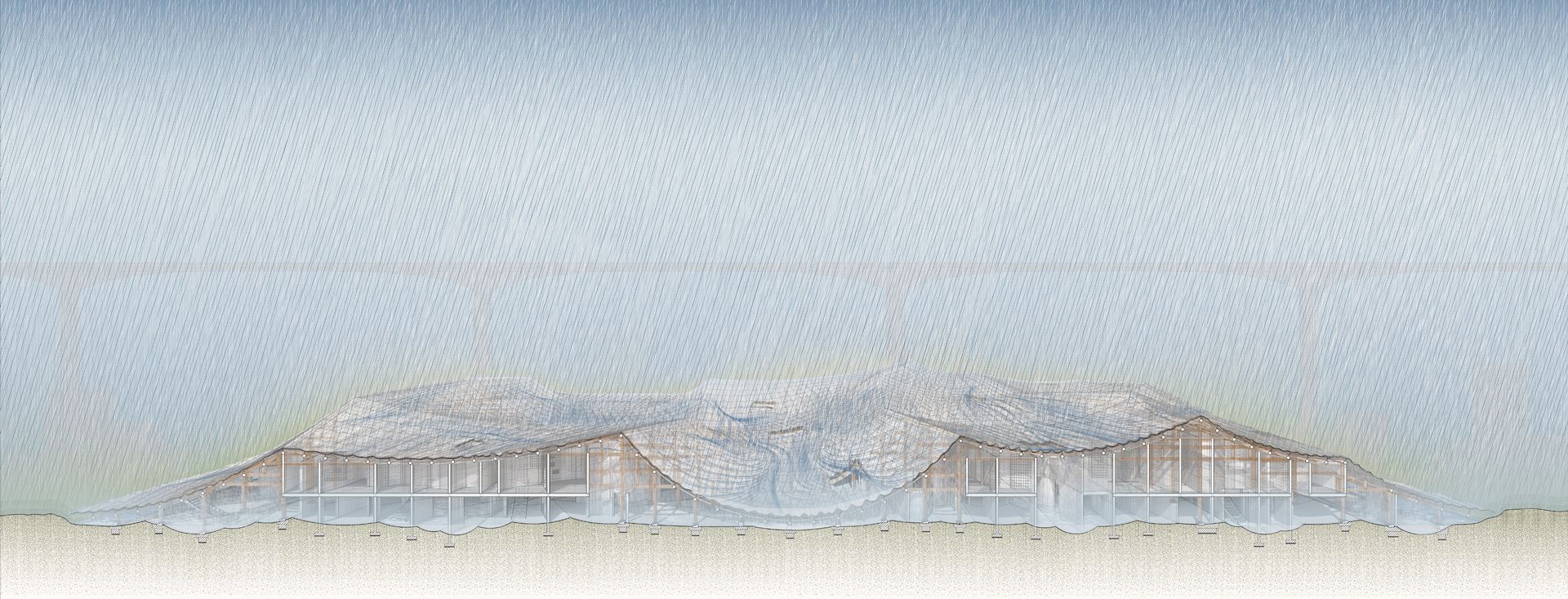

Curved roof and sculpted terrain are the main architectural language as their surfaces hold the ability for modulating the flow of water while creating opportunities for forming different inhabitations of water such as pool and stream. Roof and ground will be joined at both the periphery and some points inside the building to blur the perception of layers and enclosure. Inhabitation level will be interspersed in between, tying roof and ground together through structures and voids from the skylights. Primary curved walls are built based on the groundcontours, forming series of flexible spatial dividers for togetherness and solitude. Drawing from the ancient Lady’s Building typology, courtyards become key elements in defining residents’ gathering and living area as upper private rooms are divided into clusters and spread around courtyards.

The sculpted surfaces and curved walls not only modulate water but also these geometries fostered a symbiotic relationship between water and residents. As water flows through the building, it brings new patterns to inhabitation, moreover, it cultivates a new form of kinship model, that is based on other like-minded women rather than the traditional biological or conjugal relationship. The way they form their life network becomes a confrontation to the stigmatised singlehood living in Chinese society and it will continuously redefine the cultural norm, starting from this contemporary Zì Shū community.

The project was developed at the Royal College of Art.

KOOZ What prompted the project?

ZY This year’s brief has given me the opportunity to confront an urgent topic in the context of Chinese culture – the stigmatisation towards single women. Unmarried women in China over 27 years old are judged by both the public media and their families and be nicknamed as the Leftovers. The idea of being good wife and mother is always depicted as the ideal life path for female, meanwhile, passive judgement on single women never stops to dominate the mainstream Chinese culture. However, things are changing now and single women co-living communities are raising across the country. Personal pursuit, higher earning, educational attainment and working satisfaction are the new ingredients that have empowered these female groups to downplay the attachment of marriage to receive a better life or gain societal identities.

One single-women community in Beijing has drawn my attention, a co-living village practising land art as the dominant task daily. It’s a collective ritual of using natural materials such as water, rocks, flowers and soil to create temporal changes in landscape. Land art there has emerged as a new ritual to their community, intertwining with everyday domestic life, the ritual has redefined an alternative way and formed a new kinship net for singlehood living.

KOOZ What questions does the project raise and which does it address?

ZY I asked myself two questions prior to starting the project. Firstly, can a feminine space of empowerment be created that challenges the existing spatial typologies and redefine women’s sphere? Secondly, can land art be used as a spatial language to redefine an everyday life and form a new kinship model?

How to think of a way to connect female empowerment, community and land art together through the lens of architecture become crucial here. Water, as one of the fundamental ingredients in creating land art, was chosen as the spatial phenomena linking all the criteria. Residents’ life is fully engaged with water as the different inhabitation water creates through the year determines how the space can be used, river and rain also form various inhabitation zones that create constantly shifting spatial experiences for inhabitants. Rather than addressing questions, the flowing water brings uncertainty and temporality to the space that helps in cultivating new series of everyday rituals. The new rituals will not be bounded by traditional living, or limited to domestic labour anymore. Here the residents start exploring new daily routines together, sharing and building a different life network that is composed of like-minded friends.

Can a feminine space of empowerment be created that challenges the existing spatial typologies and redefine women’s sphere?

KOOZ How does the project explore the act of designing as one which is extremely embedded within our environment, both cultural and natural?

ZY Curved roof and sculpted ground are the basic design language as the building is imagined as surfaces to modulate the flow of water. To make the curvature more logical and systematic, both the roof and terrain geometry is defined by cone which creates multiple facets for either water gathering or diverging. Roof is the primary surface conducting the flow whereas ground terrain becomes the second modulating layer. The skylights on the roof are designed to respond to the ground, where it has opening on the roof is where to have sunken point on the ground. To orient the flow more precisely, roof tiles are given another consideration. Inherited from the traditional Chinese tile, the new tiles will have a certain direction and geometry, with either deep, shallow, single or double grooves to form a customised path for water flow.

Vertical elements are designed naturally following the ground contours. Curved walls create multiple sized courtyards in ground floor that are fluid and open for residents to experience, meanwhile they become individual units the upper floor for private living. The curved surfaces and walls not only give rise for modulating the flow of water but also they foster a symbiotic relationship between water, landscape and community. The notion of dwelling with water becomes a new culture that the community will be experiencing and adapting together as an entirety, a new family.

KOOZ How does the project approach the role of architecture beyond its physical manifestation?

ZY Instead of treating the project as a physical intruder, it works more as a mediator that facilitates the spatiality of natural ingredients. The sculpted surfaces and openings create channels, valleys and plains for natural materials to accommodate. Depending on different seasons of the year, rains, river, gravels, sand and grass filter into the building, forming intangible spatial perceptions and boundaries. Differing from the solid presence, walls and floors created here by senses are ambiguous, temporal, and immaterial, that constructs a new way to read this architectural project.

Can land art be used as a spatial language to redefine an everyday life and form a new kinship model?

KOOZ At what point does the architectural project stop and the community engage?

ZY There’s no particularly turning point in between the project and the community as they are meant to grow together in a mutual relationship. Take land art as an example, a dominant daily ritual that the community practices as to resist the cultural expectation, also a changeable landscape that defines the ground of the project. The land art created using natural materials by residents will fade away as flowing water passes through the space, in return, the shifting status will inspire people surprising ways of practising land art and other undefined programmes, therefore arouse an autonomous way of living.

KOOZ What is for you the power of the architectural imaginary?

ZY During the project, we were constantly interrogated about what is the spatial phenomena of the architecture. Aura is the new language in designing buildings as it allows us to sense the spatiality through immaterial matters, moist, temperature, environment, colour, taste, perception…For me, it gives me the power to question what exactly is a feminine collective space of empowerment and how could we start a cultural reform that renovates the traditional domestic living, to define the relationship between space, inhabitants and programmes, to challenge a distinct architectural form. Being able to translate and express aura graphically is another challenging power to grasp. How to capture the immaterial characteristics from the representation, how to exhibit an intangible world to the audience? The whole process of designing with aura is rigorous and critical as to ensure a high level of architectural resolution at the end, and it opened up a new door for me in the future to explore more of the architectural/natural/environmental relationship that lies in between immateriality, space and inhabitation.

Bio

Zhuxuan recently completed her ARB/RIBA Part II at the Royal College of Art, after having a B.Arch ARB/RIBA Part I degree at the University of Liverpool. Being raised in China and received architectural education in the western system, building placelessness and designs under western hegemony become a question that she’s interested in. In the future, she hopes to draw upon her past experiences to explore more about how architecture could be intertwining with cultural identity and modern technology.