This research questions the (in)visible traces of extraction of building ‘materials’ and their impact on the landscape. If architecture manifests itself through an act of separation – an additive force -, the use of earth resources – a subtractive force – refers to its elementary foundation. Far from having slowed down or been reversed in the face of global warming, the generalized movement of depletion of territories for the purpose of exploiting the primary resources they shelter or cover (forests, mines, agriculture, etc.) continues to grow. The example of the proliferation of suburban housing on the outskirts of Bordeaux (France) speaks volumes in this respect. The proposed architectural model questions the materials we use, our relationship with the territory and the spatialities we inhabit. An immersive exploration has taken us to the heart of the construction and transformation processes of the soil and subsoil. Our approach goes beyond simple thermal calculations to research and create a language and new spatialities. Alternative living strategies anchor a contemporary territorial narrative on material sensitivity and constructive simplicity.

The project was developed at the École Nationale Supérieure d'Architecture de Versailles (ENSA Versailles).

KOOZ What prompted the project?

CI During our training at the school, we worked individually on different themes: the ruin as a tool for architectural creation, the city and the neoliberal infrastructure, as well as the different levels of fabrication of “authenticity” and urban continuity from conception to use of spaces. The idea was to find issues common to these first researches in order to re-interrogate our way of apprehending an architectural project.

KOOZ What questions does the project raise and which does it address?

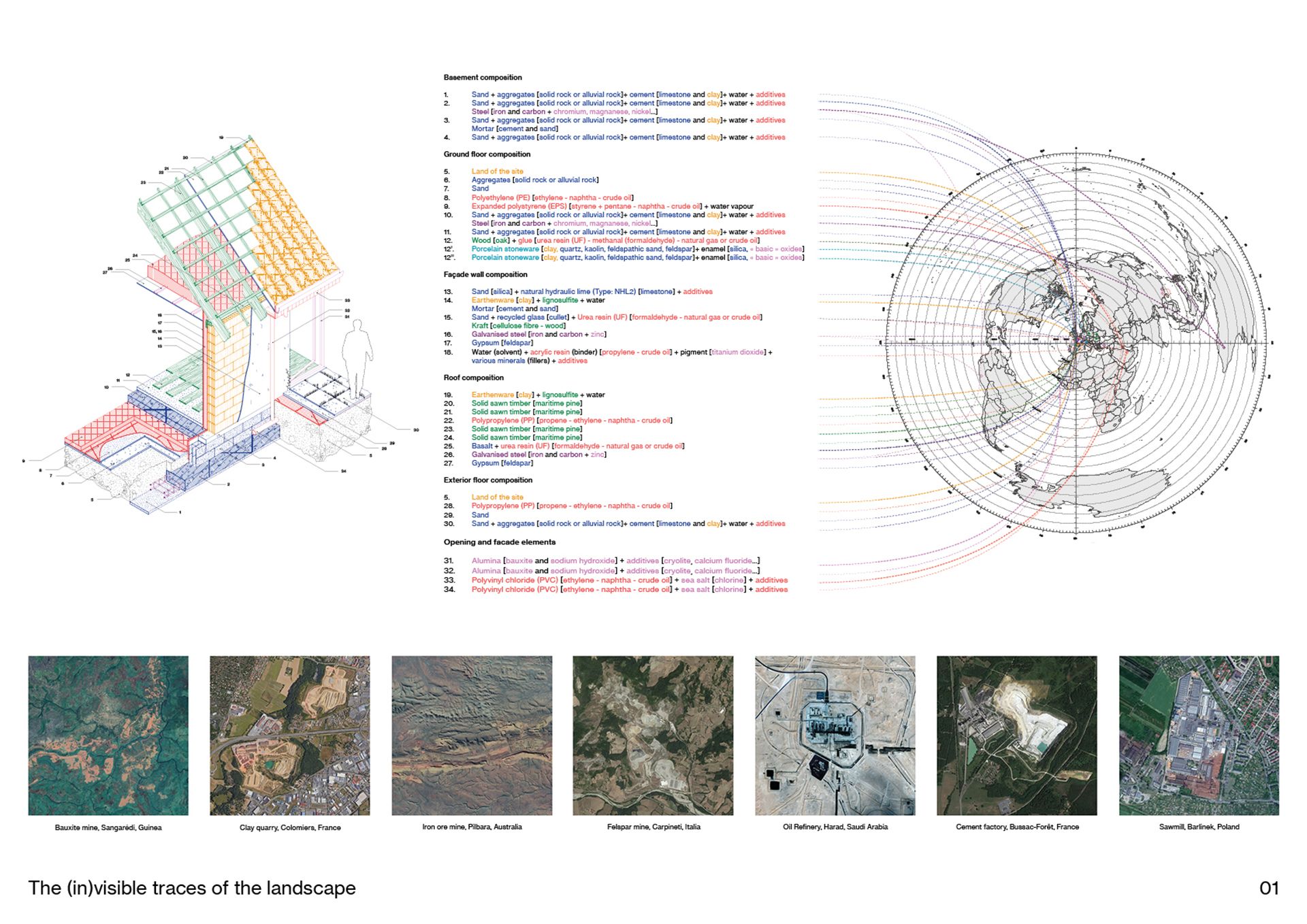

CI Our research questions the visible and invisible traces of the extraction of building materials and its impact on our territories. For us, the traces left by architecture show us that we are in the presence of an additive force (we build, we raise, we erect) and a subtractive force (we excavate, we demolish). Understanding this “material-building” story has enabled us to develop a method that draws on a variety of media. The story is broken down into several chapters, starting with the suburban housing as a contemporary architectural model that asks the question: “How do we build today?"

Then we went to meet the local actors and the resources they extract and produce located within a radius of 150 kilometers of the habitat studied.

From this territorial and material substance (wood, clay, earth, limestone, aggregates…) we made our own desires, our architectural fantasies in order to try to reveal constructive modes and alternative spatialities created essentially by the material. Finally, we played the game of choice where, from our experiments, we developed a model of localised and decarbonised “living” that differs from what we observed at the beginning of our adventure. This research into the narrative of matter is a way of making a project, of thinking before building. It is an immersive exploration at the heart of the construction process. We seek to understand a certain number of issues involved in the act of building.

The traces left by architecture show us that we are in the presence of an additive force (we build, we raise, we erect) and a subtractive force (we excavate, we demolish).

KOOZ What case studies/references informed the project and how?

CI The narrative of the soil and subsoil around productive landscapes is the result of a collaborative experiment composed with six hands. Both in its construction and presentation, this research is an accumulation of discussions, translations, close readings, juxtapositions of images, statistical analyses, and formal attempts. It is sometimes difficult to determine the origin of a particular paragraph, a particular line in the drawing or a particular idea.

Working with references is essential, if only to anchor our research in contemporary issues. Thus we visited a number of architectural exhibitions in Paris, we went to the Venice Architecture Biennale, we went to meet craftsmen and industrialists in the building sector who work in the area we explored. The trip is a founding act and a very powerful tool for accumulating references. Then there is a look at the production of contemporary architectural agencies that try to develop a language oscillating between current techniques and vernacular aesthetics. We observe, we try to reproduce in order to understand, then we go back to our sketches, we work on the material, the materials, we modify them again according to our discourse and our approach. In reality, the references are not there to validate our choices but to question them and make them evolve in relation to our personal approach.

KOOZ How did you approach the notion of "extraction" and "impact"?

CI We looked at a familiar architecture, a place we knew perfectly well – a family house, a ‘classic’ suburban model – to understand the way people build today. It is not a question of criticism but of observation. We realised that an ordinary 1:20 technical detail calls up a much larger territory, from Australia to China, via Guinea and Poland. Every building material (breeze block, tile, slab, parquet, insulation) is linked to an extraction site somewhere on the planet. This constellation of earth material extraction sites is the starting point we have chosen to understand the impact of architecture as we understand it today. Subsequently, we questioned the stages of material production to better understand all the means and infrastructures put in place to transform the raw material. New ‘impacts’ and traces left by the architecture appeared. Finally, calculations of carbon impact, construction costs and the notion of ‘capable’ architecture are ways of opening up this cyclical pattern of material transformation.

Through the extraction sites, we find an entry point that questions the conditions and impact of the construction industry on inhabited territories. Looking at the extraction of earth materials – the zero degree of architecture – is a way of reflecting on the making of the worlds of possibility in which we wish to project our existence, both as architects and as inhabitants of the Earth.

Looking at the extraction of earth materials [...] is a way of reflecting on the making of the worlds of possibility in which we wish to project our existence.

KOOZ You mention the project offering "alternative living strategies which anchor a contemporary territorial narrative on material sensitivity and constructive simplicity" could you expand on this further?

CI If territories appear as fixed entities, a research around their singular situations makes us attentive to the way in which time undoes, diverts or recycles these same situations within artificial devices. Architecture becomes a means of revealing, activating or transforming a system of alliance between materials, territories and new potentials.

The resolution to avoid wasting earthly materials and to re-engage with our materials goes beyond simple thermal calculations, and involves the making and research of a new language, new spatialities and new domestic uses. So we asked ourselves the question if aesthetics generates the dialogue between material, territory and technique? Does this mean questioning the use of building materials and their implementation?

By taking into account the manufacture, recycling, conservation and development of local construction know-how, it is a question of ensuring the “sense of living” and interacting with atmospheric variations. Thus the “architectural project” is no longer a solution to a problem or the answer to a necessity, but the starting point of a narrative, as a tool to translate a vision and to formulate a challenge that goes far beyond the initial programme or functions. It is the expression of our architectural desires and fantasies. If the ecological footprint of the construction sector must be urgently addressed throughout its cycle – from extraction to the processes of design, transport, installation, maintenance, transformation… – what built forms emanate from these reflections? How can the temporality of the material be anchored in the architectural project from its conception? By what technical means do design and style transform the implementation of the material?

KOOZ How does the project approach and explore the role and potential of the architect in the contemporary climate crisis?

CI The immense effort and cost involved in producing architecture can only be justified by the idea that it will somehow contribute to making the world a better place. As Rem Koolhaas has written, “every architect carries the utopia gene”. It is indisputable that technology and modernity have improved the quality of life for a large part of humanity, and this is also true for the construction sector. But this same construction sector is responsible for almost 40% of carbon emissions, labour exploitation and the depletion of natural resources.

At a time when the absolute urgency of the environmental crises we are facing has become clear, architecture must be fundamentally questioned. It has become impossible to ignore earthly activities in response to our ways of living. The assumption that the building industry can only meet the needs of humanity by irreversibly exploiting the environment, people and the future must be reconsidered. The ground unites all the powers of the earth in a common space that is constantly changing. It is the landscape of contemporary architectural, climatic and societal issues, a potential for the future that reconsiders architecture and landscape by integrating their construction process and uses.

If architecture is the separative force that continually emerges from the encounter between living ecosystems and earth materials, one wonders if it could be understood as a means of interdependence with a territory rather than as an agent of depletion. What models and measures could such a paradigm adopt? How does inhabiting this architecture produce a potential for regenerating landscapes and making a world of coexistences?

KOOZ What is for you the power of the architectural imaginary?

CI The diversity of the elements presented is drawn from our readings, our experiences, our travels, our wanderings, our training, the exercises carried out at school, the encounters that have changed our way of apprehending the territory and its relationship with architecture. We do not seek to produce an ideal answer, a fixed solution, but rather a physical constellation, a referenced point of view, a process to reveal a narrative around the material of the soil and subsoil, the landscape and the domestic development of territories. A selective exploration that looks at the evolution and exploitation of matter over time.

The power of the imagination is perhaps the capacity to insert itself into the changing forms of our world by producing images, methods and reflections that have a strong capacity for adaptability and evolutivity. Thus we have the power to imagine worlds in which we wish to project our existence.

Bio

Linked since their studies at the École Nationale Supérieure d’Architecture de Versailles, Collectif (in)visible is a collaborative research laboratory on the architectural narratives of the ground and the subsoil. The Collective has its origins in West Africa, Corsica and the Paris region, and is nourished by multiple experiences in Bordeaux, Paris, Barcelona, Buenos Aires and Porto. The laboratory conducts research on the additive and subtractive force of architecture. Through this reflection, the idea emerges of crossing the variable temporalities of architecture by developing an emotion between matter, landscape and domestic uses. We are looking for different ways of making projects by exploring a diversity of supports, scales and programmes.

The research “The (in)visible traces of the landscape” has been selected for the Lisbon Triennial of Architecture 2022 in the framework of the Lisbon Triennial Millennium bcp Universities Competition Award. It is on display from 29 September to 05 December 2022 at Garagem Sul – CCB (Lisbon, Portugal).

Gaspard Basnier (Architect DE)

Léo Diehl-Carboni (Architect DE)

Lawan-Kila Toe (Architect DE)