Today Europe is a single immense city. Throughout the world a proliferation of megalopolises and metropolitan areas have spread across the territory like a continuous mantle invading coastlines, valleys and plains whilst devouring thousands of hectares of nature and agriculture. The few gaps which lie in-between these sprawling urban areas have been turned into “theme parks”, and agricultural areas into large gardens, into hortus conclusus.

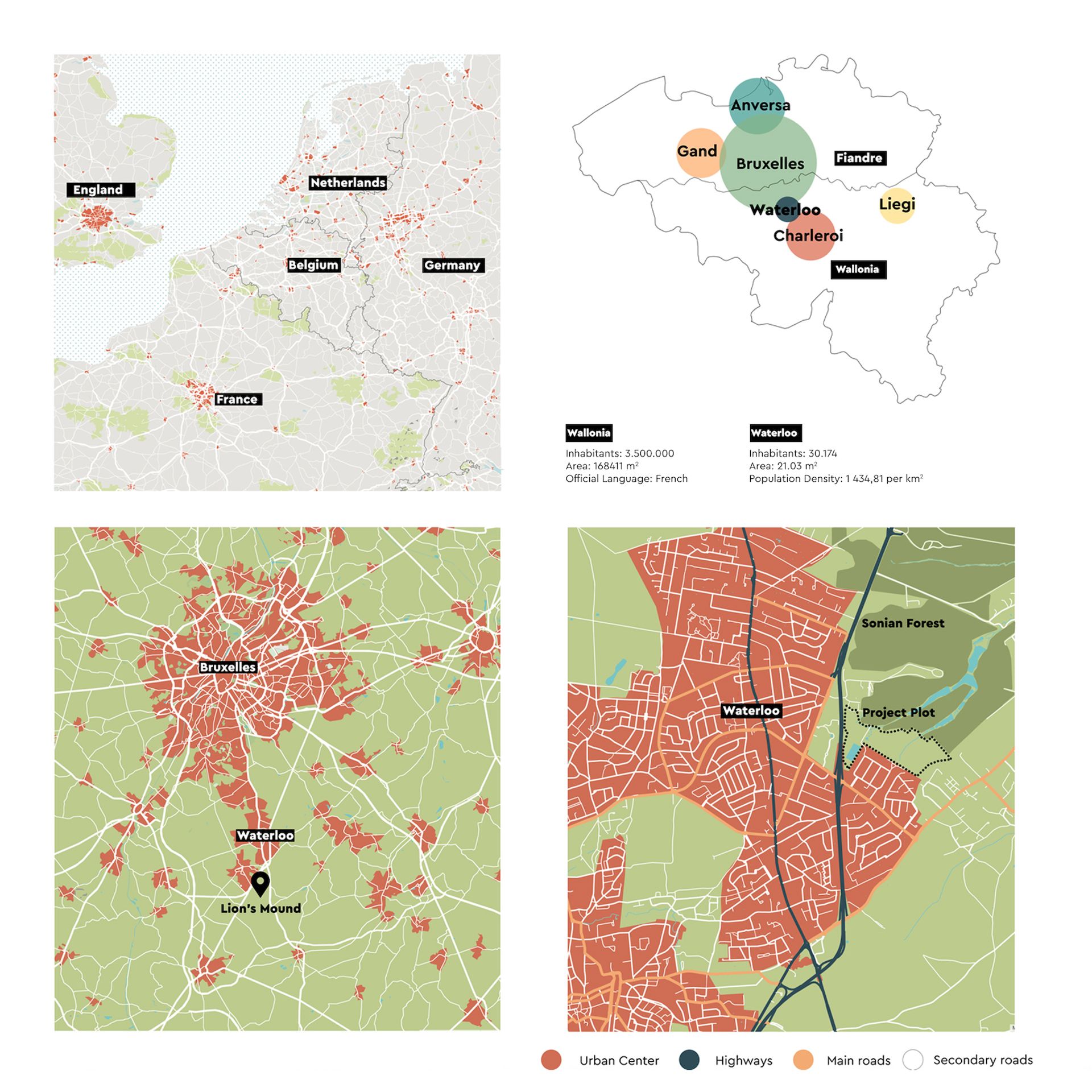

The project for an ecovillage in Waterloo, near Bruxelles (Belgium), stems from the need to re-imagine the housing block in relation to our natural landscape, a relationship which aims to qualitatively reinforce both. Within this scenario, the landscape is used as a productive environment for food, energy, water, waste treatment and biodiversity whilst the ecovillage is envisaged via a green and eco-sustainable matrix, crowned by the construction of a research laboratory for innovative agriculture. Throughout, greenery not only frames the project but permeates it, becoming an important element in the design of the building itself.

The project lot is divided into four macro-areas which have been structured according to the existing road axes surrounding the site and which recalls a large béguinages, a typical historic Belgian-Dutch medieval architecture. The latter consists in a closed inwards structure with a big garden onto which all the houses face the residential units, mixed with coworking areas, shops for basic needs and communal areas for the entertainment of the condominiums.

The building draws on the idea of the balcony as both a space of encounter and natural element. The project is articulated with three typologies of balconies: a big south-facing balcony overlooked by all the dwellings and the community roof gardens, a “community” balcony which does not solely link the individual houses but aims to become a real space of encounter for the community and a series of long balconies crafted to support climbing plants, creating true hanging gardens. To augment the continuous relationship to the surrounding landscape the project was also designed with a green roof which varies both in height (to create the impression of a varying topography) whilst also enabling the residents to each cultivate, entertain and community on their own green roof garden.

The project’s objective is crowned by the choice of natural materials and the design of an architecture capable of adapting to and coexisting harmoniously with the surrounding nature, to create a coherent urban structure – a new urban park – which highlights the significant relationship between the existing settlements, the forest and the water catchment area.

The project was developed at the University of Florence.

KOOZ What prompted the project?

GR The idea stemmed from the desire to create an environmentally sustainable housing alternative to the typical single-family villas in Belgium which, since the Post-War period has characterised the hegemony of the single-family house as a way of life – a condition created by the long-standing “anti-citizen” policy promoted by the government. This approach has today led to what appears as an endless carpet of single-family houses, served by a dense pattern of highways and railways. The project introduced of a new idea of public space and forms of domestic life beyond the single-family house.

The Ecovillage project challenges the potential of a sustainable housing block that is integrated with its immediate and more remote natural landscape.

KOOZ What questions does the project raise and which does it address?

GR The Ecovillage project challenges the potential of a sustainable housing block that is integrated with its immediate and more remote natural landscape, from its conception to execution and liveability.

KOOZ How does the project approach and redefine notions of ecology and landscape?

GR Nowadays immense urban areas have turned the few remaining natural areas into “theme parks”, and agricultural areas into large gardens, into hortus conclusus. The aim of the project is therefore to bring architecture and nature together in a critical and meaningful way which does not rely on what is today commonly referred to as “greenwashing” – where nature is used as an accessory and decorative element.

The 416,000 m2 site includes a wastewater collection basin, an agri-food research centre, cultivated fields and is in close proximity to the famous and imposing Soignes forest. The 0 motorway, which separated the site from the city centre of Waterloo, is addressed as a forest gardening project with the ambition of creating a green acoustic cap to mitigate sound and purify the surrounding air. Within this context, vegetation is designed to form a continuous green filter between the inside and outside of the homes, absorbing fine particles produced by traffic, producing oxygen, absorbing CO2 and protecting the terraces and interiors from noise pollution. The urban, natural and rural spheres coexist by creating a unique and integrated architectural and ecological environment at every scale of the settlement.

KOOZ Today the construction industry accounts for 38% of total global CO2 emissions, in your opinion, how can we build better?

GR With the advent of the Anthropocene, the Earth’s fragile balance is being severely altered by the increasing of emissions from human related activities and is resulting in catastrophic environmental incidents which have and continue to impact millions of people, with even greater effects on those living in the most vulnerable areas and threatening vital species, habitats and ecosystems.

Building better can be achieved by putting more emphasis on the sourcing of sustainable materials, the use of energy from renewable sources, the retrofitting of existing structures amongst other approaches.

KOOZ What are for you the greatest challenges for sustainable architecture today and in the coming years?

GR For me the greatest challenge is of maintaining a healthy and balanced planet biodiversity which can and must also be addressed through architecture. As architects we should think of nature at the heart of every project from the building to the city. Although we may not be able to recreate a real forest in the city, this does not mean the two are not compatible, rather we should explore ways of merging the natural environment, architecture and technology for greater coexistence and cooperation. The dualism between city and nature, that conflict between social constraints on the one hand and primordial freedoms on the other, is a recurring theme in Western thought. As the urbanisation of the planet is growing at a rapid pace and the individual is turning into an ‘indoor animal’ – divided between office, home and car – the need to integrate nature and the built environment is becoming more acute than ever. Tomorrow, thanks to more reasoned urban planning and also to new technologies, this reconciliation could become closer.

The aim of the project is [...] to bring architecture and nature together in a critical and meaningful way which does not rely on [...] “greenwashing”.

KOOZ What role should academia hold in addressing the climate battle and the role that architects can play within this?

GR The academic world plays a predominant role in the fight against our changing climate as it should inspire the young architects of today to operate with environmental and ethical values at their core. I firmly believe that good basic training in environmental issues, climate protection and green construction, with new and increasingly innovative materials, can really shed hope on tomorrow’s architecture.

KOOZ What is for you the power of the Architectural Imaginary?

GR I believe in the great gift of being able to imagine and visualise an ideal and utopian world, then being able to transpose it into reality, acting as a valid visualisation tool. It is like an infinite sheet of paper that we have at our disposal, always ready to receive the best version of the project to come.

Bio

Giulia Rivellino is an italian architect now based in the North of Italy, with a Master’s Degree in Architecture from the University of Florence. After graduation, she joined EMBT Miralles Tagliabue in Barcelona, where she collaborated in international projects and competitions. She has always been interested in the union between architecture and greenery, trying to develop projects that could give life to the perfect mix between the two. She is also passionate about art and all its variations, trying to improve her skills in artistic visualization.