Long gone are the days where the worst thing that could happen is a flood. The year is now 2070, and despite the seemingly irrevocable truth of significant riverbank recession along the Thames Estuary, the commoners of East Tilbury are enthusiastically waiting for the next tidal shift…

Through an investigation into the multiplicity of “Utopias” that could arise on site, a participatory device that engages with local residents and actors on designing and co-producing these incomplete, and envisioned futures was developed. Having developed a working methodology in engagement practice, we move to the Bata Estate in East Tilbury, a radical company town which was once at the forefront of live-work relations and modernist construction which has fallen into a state of precariousness and deprivation since the shuttering of Bata Shoes.

Through the toolkit, a catalogue of resident’s memories and ambitions for East Tilbury were developed, where the written thesis develops this into a pluralistic mode of participation that enables multiplicity in urban ambitions and “utopias” to be made visible.

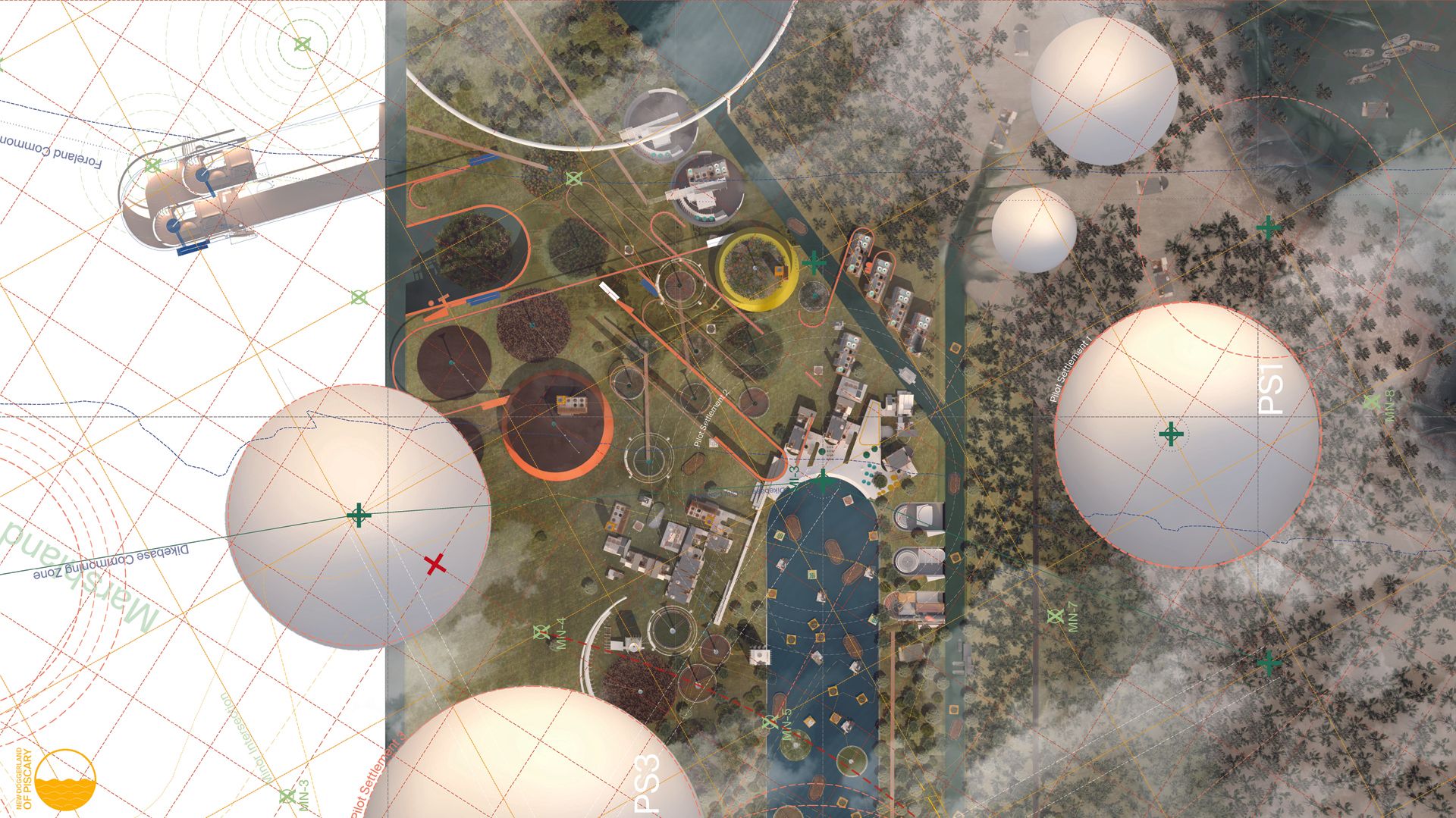

Acknowledging the socio-ecological crises that are resultant of our extreme consumption and resource extraction, a dynamic, reactionary and arguably incomplete “master” plan is proposed… Instead of working against the forces of nature, the comm(o)nity of East Tilbury has long sought to return to a nomadic way of life, forgoing the rampant pressures and excess of the neoliberal city for something more attuned. Re-turning to principles of the historic commons, their settlement has been designed with the foresight of adapting to change in both land and waterscapes, where the dynamic (master)plan is built across time, seasons and tides to speculate with new forms of living. The riverbank has receded, but unlike predictions in the early 21st Century, the Thames has been deliberately widened as a catalyst.

Developing from an initial afforestation of the marshland ecology, a soft system for the production of the commons began, fifty years ago, as a series of ponds, forests, polders and waterways to seed the New Doggerland of today. Driven by the historical principles in Commoning Of Piscary, Of Estovers and In The Soil, living with the community involves a new relationship to the water/land through seasonal consumption of agriculture and stewardship of the river and forestery as examples. Learning from Bata’s preconstructed components, the New Doggerland is expanded through a “Common Language”, where moulds and materials are re-used to expand, or decrease spaces according to the population, needs, tidal ecology and environment. Simultaneously safeguarding the historic Bata Estate further inland, the common contemplates on an approach to architecture that is post-compositional, reactionary and embedded within our larger ecological systems, contributing beyond the wellbeing of its inhabitants and habitat(s) of the estuary. Instead of building from (and against) the water, flooding becomes an opportunity to re-arrange and expand commons living across the Thames to Coastal England.

The project was developed at the Bartlett UCL Faculty of The Built Environment.

KOOZ What prompted the project?

YS In times where politics, ecological disasters and the grip of “the economy” calls into question how individuals, collective action and design-thinking can enable urban change. With a research interest in enabling agency and collaboration between communities within and alongside existing actors/institutions in the built environment, the project was prompted by the notion of ‘Re-Utopia’; looking back to the ambitions and values of the post-war world that influenced modernism as a catalyst for disrupting our attitudes and methodologies for approaching architectural design. Sited along the Thames Estuary, the vulnerable landscape and its current decline in biodiversity further empowered the need to fundamentally rethink and respond to our impact on natural ecosystems. Concurrently, the lack of citizen-lead agency over the production of the built environment has informed a design method that is rooted in translating meaningful, considered participation into (eco)systems for living.

With a research interest in enabling agency and collaboration between communities within and alongside existing actors/institutions in the built environment, the project was prompted by the notion of ‘Re-Utopia’.

KOOZ What questions does the project raise and which does it address?

YS This project seeks to challenge our current understanding of the (built) environment through a bottom-up lens. Rooted in participatory practice as a springboard to investigate an ecological-systems approach to design, I investigate alternative methodologies that allow for critical engagement and the inclusion of difference in relation to architecture, ecology and the built environment.

Plur-ticipation applies theory around commoning and participation into a propositional pluralistic participation that is tested on site to analyse its ability to involve and address the multiplicity within communities, which challenges traditional participatory process to move beyond a goal for immediate mutual consensus. Through these local multitude(s), expressions of the larger social whole are explored through designing to local agonisms of Community, Liveability and the Environment. Living with (and not against) the land and water became instrumental in developing the project forward. As the traditional masterplan in architecture and urban design is deemed to be a static, regimented, top-down approach to organise social existence since the industrial revolution, a search for something more nuanced and attuned to natural rhythms and systems becomes apparent.

Responding to the inevitability of rising sea levels as a result of Climate Change and melting polar ice caps, the project seeks to address and propose a responsive scheme that takes into account the entire ‘supply’ chain (or as I see it, our shared Common Pool Resources) in the design, management and stewardship over the wider ecology and it’s use in collaborative construction.

KOOZ What role does academia play as a role for the development of thought-provoking ideas and architectural models?

YS Academia acts as an intersecting contributor to this playground of the architectural imaginary as it seeks to question and push the boundaries of normative design in existing domains. As an intergenerational and intercultural space, the fusion between ambition, vision and experience creates crucial mind-spaces that cultivate responsive and responsible designers of the future. Models of architecture should more now, than ever become intersectional in their pursuits for generating knowledge as the existing silos of specialisms creates barriers to understanding the world as the multitide (which informs a fragmented, collective whole). Fundamentally, how can we imagine building (verb? Noun?) as pedagogy?

KOOZ How has this project influenced and informed you approach as an architect?

YS I have always been interested in examining the pedagogical potentials of architecture in society, with a keen interest in social and participatory design. Understanding the privilege that has situated me within the practice of architecture, I believe that as generalists and effective collaborators, we have the ability to bring voice and agency for those that have been left behind and disregarded in our modern production of the built environment.

Through challenging the normalised roles of the architect, alongside designing systems that enable people and communities to have a stake in the planning, design and construction process of what is still largely seen as ‘master’planning at policy level, perhaps this project has further expanded the notion of creating democratic forms of living beyond our species to become symbiotic and care-ful with our planetary ecology.

KOOZ What are, for you the greatest concerns that the contemporary architect faces?

YS In my opinion, the greatest concern that the contemporary architect faces is how to mobilise our collectively in addressing the climate emergency, understanding our role and responsibilities within the larger ecological systems and creating innovative ways to respond, augment and correct the extreme levels of social injustices that exist in our civil societies.

KOOZ What is for you the power of the architectural imaginary?

YS For me, the power of the architectural imaginary is its ability to respond to existing qualms and inequalities in search of “new ways of living together” and radical “ways of representing collective life” as John Thompson would describe it as an anthropological extension to Satre’s concepts on imagination and human consciousness. This dynamism that the architectural imaginary encapsulates which transcends the built into notions of “collective experience” (Clark, 7) allows for a playground that is fertile with disruptive thought to co-create a better, symbiotic future. The reification of the imaginary into imagery, prose, research and experimentation frees us of the limitations that exist in Architecture (with a capital A) to provocations that formulate possible solutions to wicked problems.

[...] the power of the architectural imaginary is its ability to respond to existing qualms and inequalities in search of “new ways of living together” and radical “ways of representing collective life” [...]

KOOZ What is for you the architect’s most important tool?

YS The architect’s most important tool is their ability to critically speculate on inhabited futures and act as a collaborator within transdisciplinary teams. Mediating between knowledge and discourse as vision and its translation into lived and material cultures, this neurological process and system of thought to action/implementation/construction allows us to design potential solutions to the ‘wicked’ problems that pervades through society today. This perceived dichotomy of the specialist-generalist could very well serve as a tool for disrupting existing (infra)structures of social governance. In addition, the altruistic architect’s role as an empathetic educator that enables and understands our shared existence as an ecological whole is crucial to making, collaborating and designing an urgent symbiocene that is less precarious, unjust and capital driven.

Bio

Yip is an architectural designer and photographer, having completed his Masters in Architecture at the Bartlett, with a keen interest in social and participatory design. His research examines the pedagogical potentials of architecture in society, where his projects speculate on the wider role of the architect through proposing socio-material frameworks and forms for democratic living and engagement.