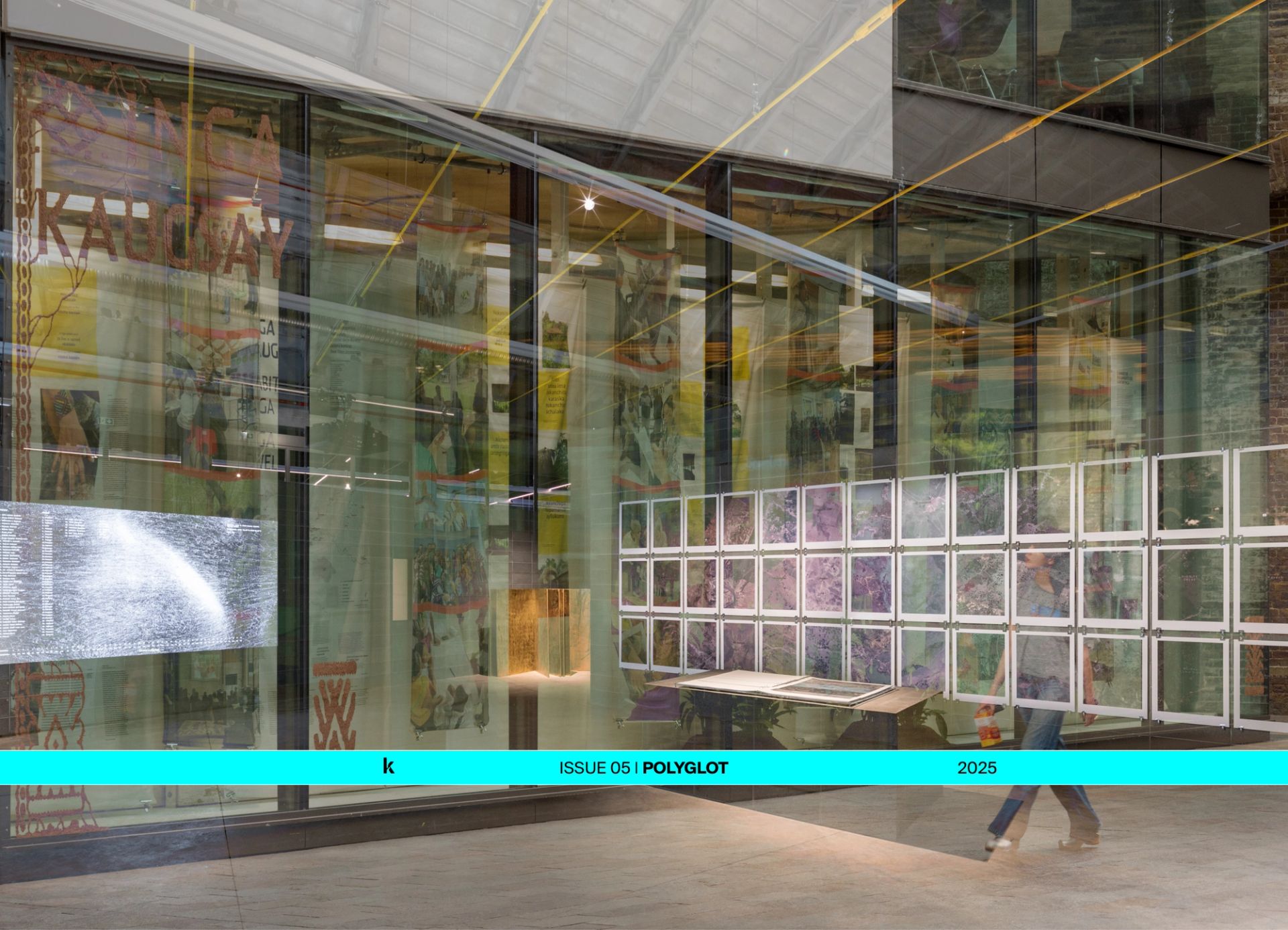

Part of the ongoing action towards decolonising our intellectual and political frameworks involves uncovering, confronting those parts of our pasts that have been suppressed, elided and hidden away. African Venice (wetlands, 2024) is a new publication which seeks to reveal — through a series of walking tours — the histories of Black peoples in Venice, from the middle ages to the present day. From images of Africans in artworks, through painful legacies of slavery and Italian colonialism, these tours are lyrically enriched with poems, essays and reflections on Venice’s Black past and present. Writer and journalist Igiaba Scego’s foreword, republished below, frames the contemporary need for these stories to be told.

Jacopo de’ Barbari, Venice, Bird’s-Eye View, 1500 Museo Correr, Venice (detail of Black Wind-head)

The year 2020 was a pivotal year for people of African descent. A year in which obsessions, fears, struggles, searches and paths culminated. The year in which an African American called George Floyd, a name that has now become part of our skin, was barbarically murdered by Minneapolis police. What Black people, myself included, saw in that murder, in that knee on the neck that literally took Floyd’s breath away, was the destruction not only of the individual, but of a Black, male, female, transgender, nonbinary collectivity. A destruction rooted in distant centuries now behind us. The latest episode in a chain of oppression in which the Black body was downtrodden, humiliated, raped, vilified by an abusive colonial system. There were protests, of course, and fights against systemic racism. There was the desire of so many people to change society at its core. There was a revolution, to the cry of Black Lives Matter. The movement swept through the United States, but from there it then expanded to reach every geography. Among these geographies there is Europe of course, with its load of unspoken guilt. In today’s public discourse, especially by European institutions, the continent is still seen as an isolated “garden,” opposed to the “barbarism” that surrounds it. An “us” versus “them,” a civilised being pitted against an uncivilised one. But who are “them?” It is on this “them” that the attention has focused since the murder of George Floyd. The long wave of outrage that came from the United States hit Europe like a slap in the face, immediately pointing out that “them” and “us” were mixed up, that we are them, while “them” is actually another name for “us.” That is, European societies were and are plural, with sinuous histories and composite identities. This “us” does not point to sad, isolated and empty gardens, but rather to interwoven threads, as in the quilts sewn by grandmothers. A patchwork of colours as in Harlequin’s costume.

In today’s public discourse, especially by European institutions, the continent is still seen as an isolated “garden,” opposed to the “barbarism” that surrounds it. An “us” versus “them,” a civilised being pitted against an uncivilised one.

In this Harlequin-Europe, the Black presence, that European Afro-descendance that for a long time no one wanted to see or to name, actually had a place of assured prominence. In Europe, one of the first consequences of the murder of George Floyd was to unleash protests (the most emblematic one in Bristol when the statue of the slave trader Colston was thrown from its pedestal and then rolled down to the river), as well as to give prominence to performances or stances of what we might call Afro-European identity.

It is necessary here to take a moment and understand the meaning of this terminology. What sense does it make today to put the word “Africa” and the word “Europe” together? What group does it define? And what vocabulary does it produce? On the model of the term “African American,” or “Afro-American,” people of African descent born and/or raised in Europe (including first-generation migrants who felt their identity had changed) also wanted to give themselves a collective name. It happened through trial and error, abjuration, reflection and rethinking. It must also be remembered that the names used today, and accepted by activists, scholars or artists, may in the future go through partial or radical changes. The fact remains that after attempts linked to individual nations and not always accepted by communities, such as the term Afroitaliani, it was the term “African Europeans,” without a hyphen, that has had the greatest acceptance. Because it actually defined a Black identity different from that of African Americans, an identity of Black European people, or “Afropean” as in the very successful title of Johny Pitts’ book, where the African matrix remained strong and was married to a European identity that was not passively worn – not therefore the “garden” of European institutions – but rather actively, that is, through the history and analysis of a systemic dilemma that saw Europe as the precise cause of Africa’s suffering: Europe as a device of violence, but also as a problematic house for the Black body. So the idea was slowly taking shape of Europe as a crossroads, a place where battles for Blackness had been fought for centuries. A Black body that had lived marginally, narrowly, whose history had been erased, but which was finally becoming self-aware. So it was vital to juxtapose the word “Africans,” with the word “Europeans,” because they were in fact the words of self-definition. People born and/or raised (or long settled) in London as in Rome, in Dublin as in Paris, in Berlin as in Lisbon, united by two continents often in conflict. Moreover, the term summarised a different history from that of African Americans; it was not only a history related to slavery – which existed in Europe too, but in different ways – but also to colonialism. And it was this history that had to be investigated. There was a need to become aware of themselves not only generically as Black people – or even worse as a people marginalised by the history of preeminent Black groups, such as the African American community which led the struggles for civil rights – but as Africans Europeans. It became essential to manifest themselves and their own histories. It is no coincidence that in recent years a great number of books on this have come out: just think of Anglo-Nigerian writer Bernardine Evaristo’s successful novel, Girl, Woman, Other, the narrative of one hundred years of history of Afro-British women, which mixes together political, intimate, social and historical experiences; or historian Olivette Otele’s beautiful volume, African Europeans – The Untold History, a promenade through the history of the Black presence in Europe.

What sense does it make today to put the word “Africa” and the word “Europe” together? What group does it define? And what vocabulary does it produce?

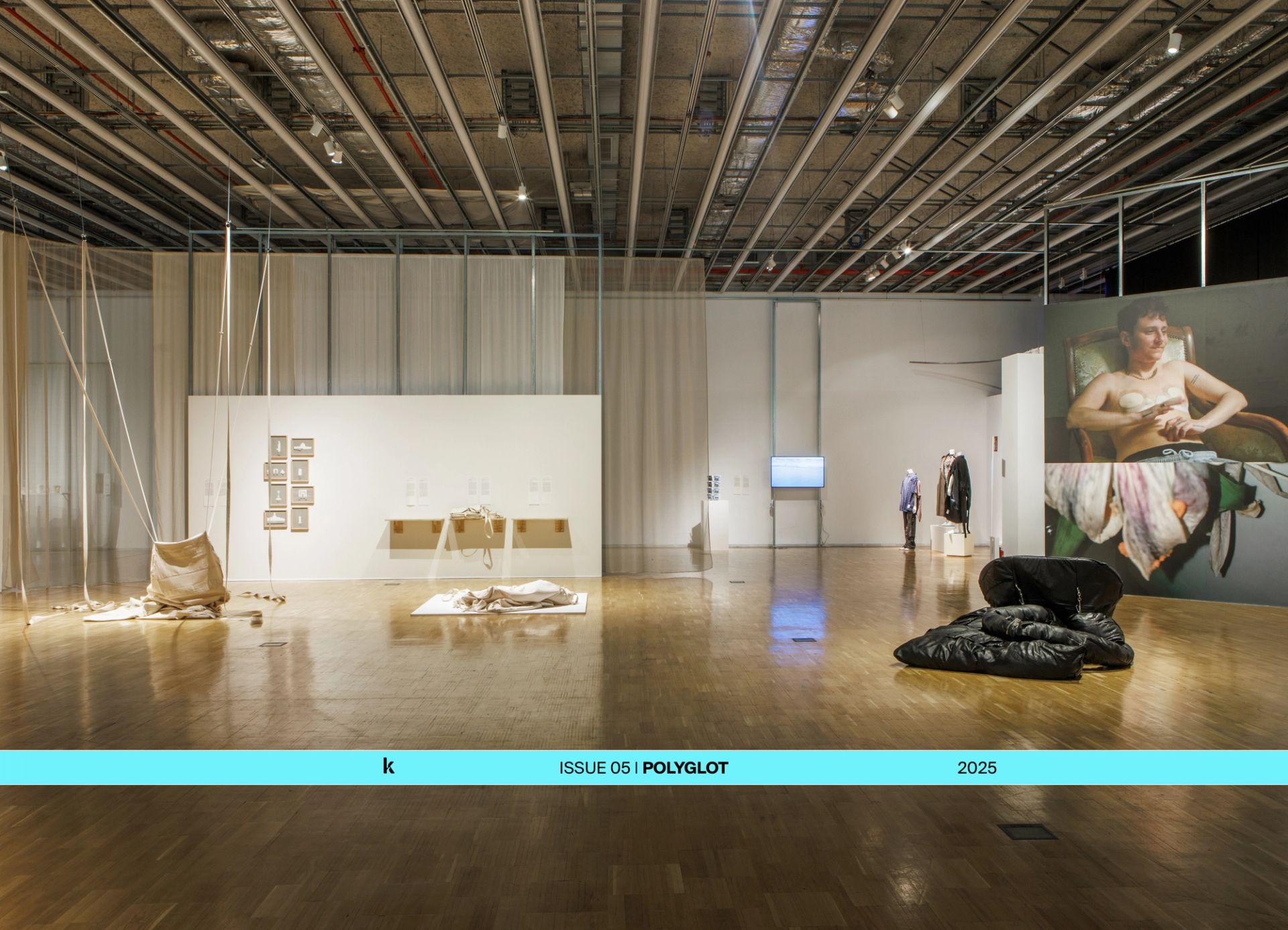

Inevitably the whole process led to looking at Europe’s artistic heritage as a litmus test, almost as circumstantial evidence to be presented to a hypothetical tribunal, of a real, tangible, visible Black presence on European soil. And thus Black people previously invisible in Renaissance canvases as in those of the Impressionists were not only seen as if they had come out into the light for the first time, but also analysed and finally included in a temporal chronology of European Blackness. A revelation, in short. So the various works of Carpaccio and Veronese, but also Degas or Manet, provided flashes of lived life, illuminating with a stroke the many centuries crossed in silence.

In this, Venice is a central city. And the book you have in your hands is precious for the itineraries proposed and the reflections shared.

Venice must be stripped of all romanticism (especially the cheap version of it) and seen as it was: a geopolitical player that until its decline in the 18th century played a central role as a Mediterranean power. A city of commerce, of riches, of intrigue, of courts, of trade with the East and the Global South. Venice, which as early as the 15th century was what New York or Shanghai are today, that is, a centre of plurality, of crossbreeding, of grinding power, but also a key for the future.

Today a Black person arriving for the first time in Venice will experience the estrangement typical of someone who has never seen the lagoon, but will also realise that the city is intimately linked to Blackness.

Today a Black person arriving for the first time in Venice will experience the estrangement typical of someone who has never seen the lagoon, but will also realise that the city is intimately linked to Blackness. Venice, like Livorno, like Trapani, like Naples, like Messina, like Rome, is in fact linked to what historians such as Salvatore Bono and Giovanna Fiume have defined as “Mediterranean slavery.” Many people, not only Black, especially those from Anatolia and North Africa, were enslaved in Europe, in Portugal and Spain, but also in Sicily and Campania, Tuscany and Veneto. Slavery followed the caravan and slave routes traced by ancient African kingdoms and Arab traders; the Portuguese were the main driver of the Atlantic trade (and the link that created the nefarious connection Blackness-goods-slavery) and the leap from Lisbon to the whole of Europe was a straight one. There is a well-known late 16th-century painting by an anonymous Flemish artist, now housed in the private Berardo Collection in Lisbon, where the Alfama neighbourhood (that centuries later would become known for fado), and the very central Chafariz d’El Rey, is populated by Black people. Upon close observation, one will notice that each painted character corresponds to a different condition: there are water carriers, servants, jesters, outlaws taken offstage by gendarmes, musicians, intellectuals, and there is even a Black knight on horseback: people in a state of slavery and people who had somehow made a social ascension. The reality described in Venice is basically similar to Lisbon. A Black enslaved presence, but here too with concrete possibilities of social ascension. We can be confronted with Black men depicted with rough, stereotypical features, abased by their status, holding up the tomb of a doge, and then move on to elegant gondoliers dominating foreword the Rialto stage or to the moving body of a Black man depicted by Gentile Bellini without distinctive facial features, identified by a cloth covering his nudity and by his Black skin, immortalised at the moment when he dives (or is urged to dive by a woman behind him) to retrieve together with other fellow citizens a precious relic accidentally fallen into the lagoon. A man from the past who also painfully reminds us of a man from the present, Pateh Sabally, 22, a Gambian, who committed suicide in 2017 in the Grand Canal, under the weight of a Europe that is not a garden, but a fortress, with Black Africans denied the possibility of legal travel.

Ah, if only these paintings could speak, have a voice, an accent, a sound texture. It would be nice to hear their Venetian cadence, so musical. A cadence that would be mixed with that of so many Afro-European/African Europeans who, seeing them, would mix their English, French, Portuguese, Swedish with those ancient idioms. And therein lies the estrangement brought by the book you now have in your hands, a book that speaks to us about art, history, city life, and about that lagoon whose singular nature is hard to fathom for those who have not grown up with it. A book that puts the Black body at the centre of the life of a European city, as has rarely been done in the past.

Bio

Igiaba Scego is a Somali Italian writer, public intellectual and scholar. Her numerous, award-winning publications include, in English translation, the novels Adua (New Vessel Press, 2017), Beyond Babylon (Two Lines Press, 2019 ), and The Color Line (Other Press, 2022).