My own journey into real and imagined forests began circa 2009 when I stumbled upon an aerial photo (Fig. 1). What seemed at first like a photoshopped image was in fact a real pattern in an area in Montana, known as the Checkerboard Cascades. The unnatural checkerboard pattern was based on the American one-mile grid and was the result of an economic transaction – the land given in alternating sections to the railroad companies in the 1850s in order to sponsor their risky track-laying operations. The sections were given in alternating sections so that the federal government could speculate on the remaining squares in the opportune case that their value would rise. Years passed, and the railroad companies who cut the trees sold their lands to the forest companies, who clear-cut the forests, and so the pattern remained visible for 170 years. Going there and seeing two quarter square-mile forest tracts gently touch each other at but one point, it occurred to me that form in forests can be the basis not only for infrastructural development, but for ecological patterns.

Figure 1. Checkerboard cascades, Montana, 2008

This observation was made decades before my excursion by prominent ecologist Richard T.T. Forman who, starting the 1980s, published several scientific papers in collaboration with expert foresters associating forest form and ecological performance.1 Significantly moving beyond methods of visual analysis then prominent in forestry, Forman suggested that introducing changes to the form of the forest can become the means of interaction with ecological processes. This meant that deliberate acts of formal design could become the medium through which both landscape and ecological patterns could be created.

Forman suggested that introducing changes to the form of the forest can become the means of interaction with ecological processes. This meant that deliberate acts of formal design could become the medium through which both landscape and ecological patterns could be created.

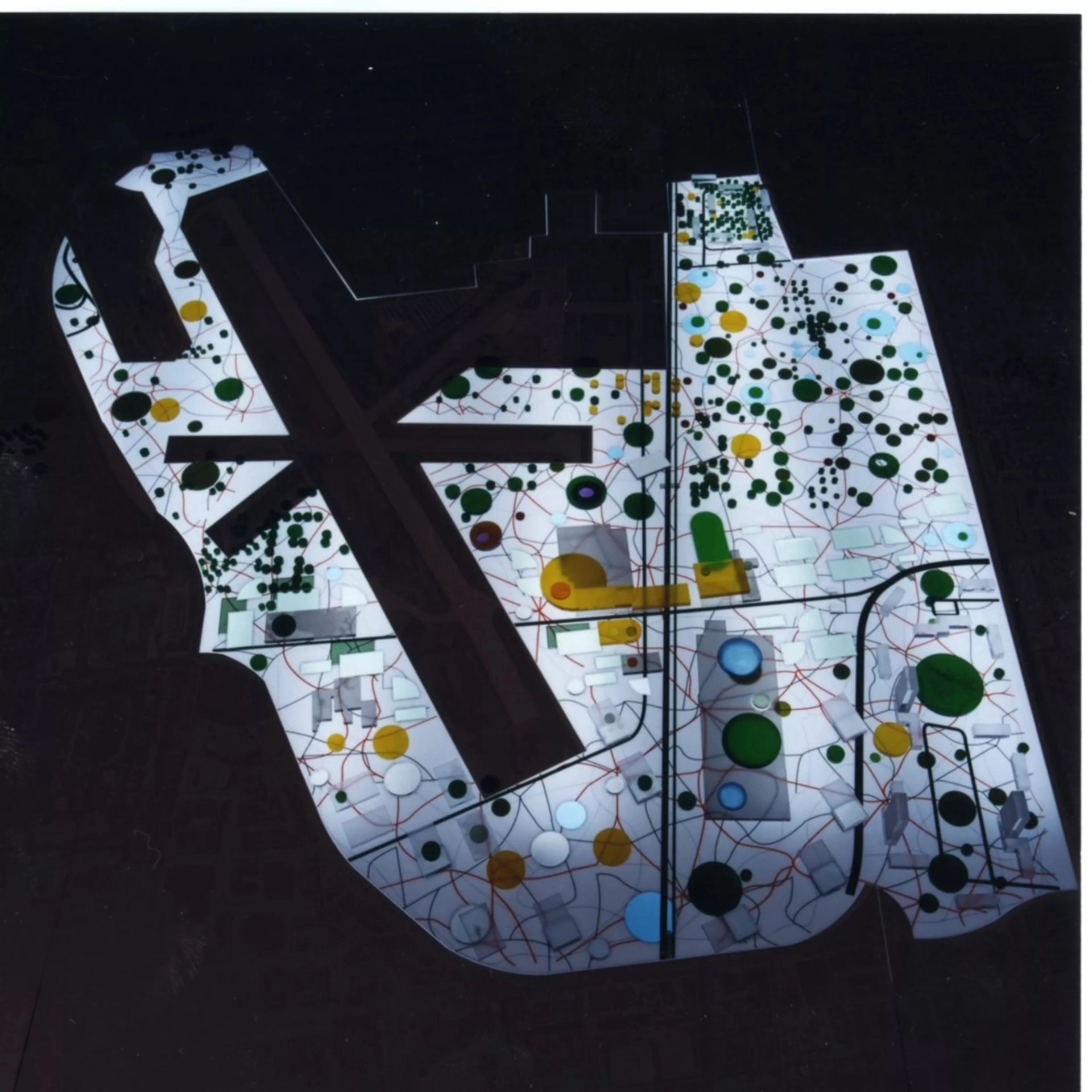

Which was ostensibly the attempt when OMA presented a large number of forest circles in their joint proposal with Bruce Mau to redesign Downsview Park in Toronto (2000). “Tree City” was aiming to use form in order to create an infrastructure that would be resilient enough to sustain the financial and political uncertainties marring the feasibility of the project (Fig. 2). Looking at the scheme, in which 25% of the area was to be covered by “tree clusters”, it is tempting to consider the ecologies that could be designed, but this is a retroactive manifesto. Neither the written descriptions nor the design itself betray any real intentions to interact with ecological complexities. From a forest standpoint, the Downsview Park rehearses ages-old rhetoric about the magical power of trees to wins hearts and minds, and so transform even the most derelict urban environment.

Figure 2. OMA, Downsview Park, Toronto, 2000

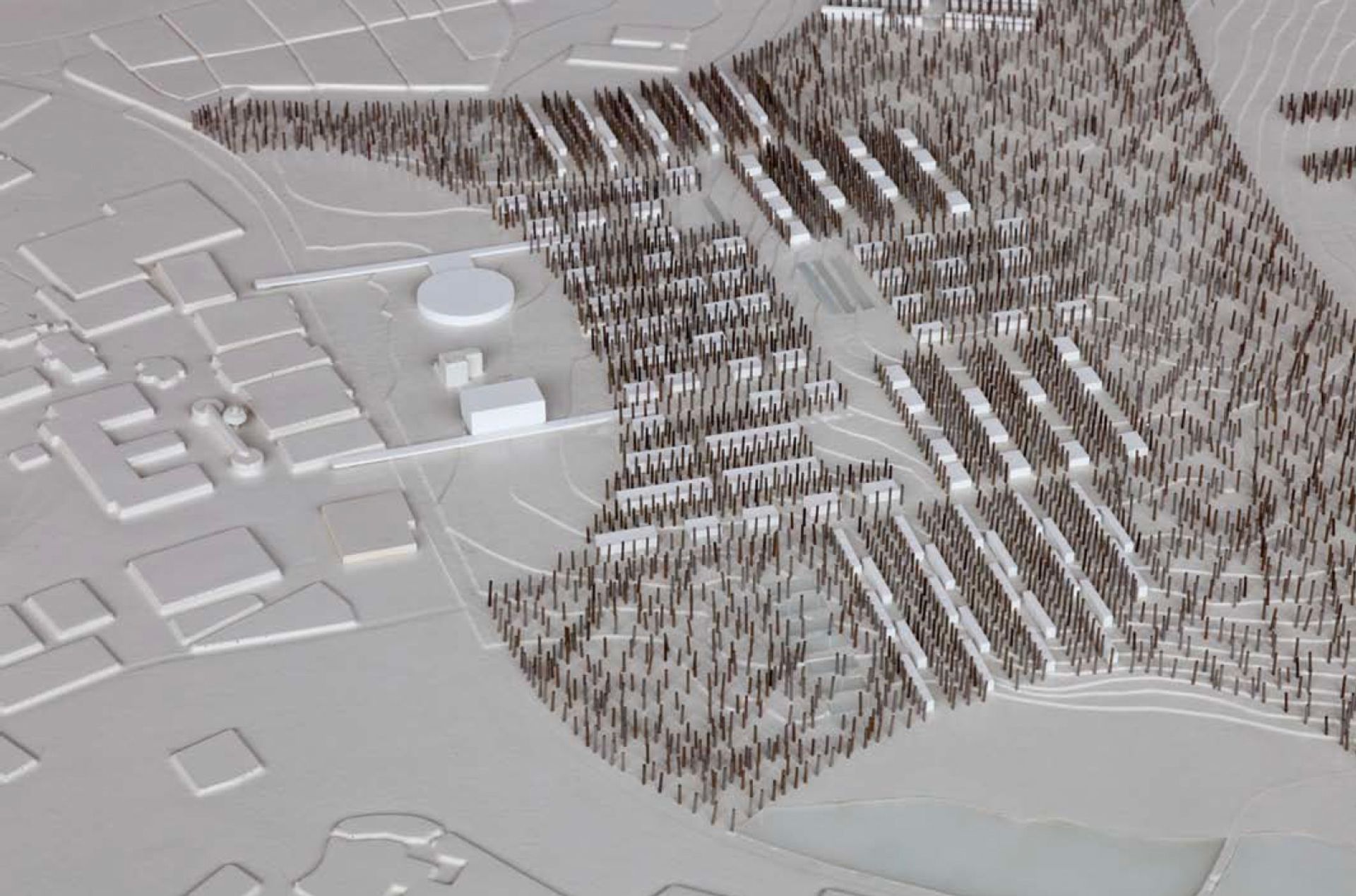

Several years before the Downsview competition, Herzog & deMeuron submitted a more nuanced forest proposal for the masterplan of the Hannover Expo, planned to open in 2000. The firm produced an unconventional scheme, which was essentially a vast planted forest in which both organic and inorganic life were designed in the same way (Fig. 3). The new quarter took its outline from the topography of a nearby mountain and the arching contours of the surrounding highways, but its internal organization was determined by close relationships between trees and buildings. The firm invested much effort in historicizing this relationship, looking at previous architectural types and carefully defining their appropriate forest counterpart.

Figure 3. Herzog & deMeuron, Hannover Expo masterplan, 2000.

The proposal didn’t win the competition, but clearly if implemented it would have recreated the ecology of the region.2 Not only would it introduce a form whose characteristics would determine the complexion of biological life, but even more specifically, by creating interdependencies between architectural and forest forms it would have relinked humans and plants in new ways. At the same time, this was not a project of camouflage, seeking to cover everything in green. Designed form still took the lead and was used in a way that remixes our expectations – resulting in what Herzog & deMeuron call in their proposal “a piece of architecture-nature”. In retrospect, the Kronsberg Forest can be regarded as an antidote to what Jacques Herzog calls “a more decorative attitude… where you build trees into buildings.”3

*Parts of this column will be published in the upcoming book Touch Wood: Material, Architecture, Future (Lars Müller, 2022).

Read the entire "The Forest Con" column by Dan Handel.

Bio

Dan Handel is a curator and writer working on research-based projects with special attention to underexplored ideas and practices that shape contemporary built environments. He created forest-related exhibitions for the Canadian Centre for Architecture (CCA) in Montreal and Het Niewue Instituut in Rotterdam, published texts on the subject in the Journal of Landscape Architecture (JOLA), Harvard Design Magazine, and Cabinet Magazine among others, and lectured widely on forests and architecture, most recently at the Prada Frames symposium during Salone del Mobile in Milan. He is currently developing a manuscript on the uneasy kinship between design and forests, to be published in 2024.

Notes

1 Franklin, Jerry, and Richard T.T. Forman. “Creating landscape patterns by forest cutting: Ecological consequences and principles”. Landscape Ecology 1, 5–18 (1987).

2 Had they won the project, Herzog argued that the first order of business would have been to bring in experts in biology and land transformation in order to calibrate the proposal. Jacques Herzog in an interview with the author, November 5th, 2019.

3 Jacques Herzog in an interview with the author, November 5th, 2019.

Bibliography

Czerniak, Julia. CASE: Downsview Park Toronto. (Munich; New York; Cambridge, Mass.: Prestel ; Harvard University Graduate School of Design, 2001).

Forman, Richard T. T. Land Mosaics: the Ecology of Landscapes and Regions (Cambridge; New York: Cambridge University Press, 1995).