The process of world-building is characterised by the interactions between the codes that compose its structure. The inevitable problem of how these single elements gather to form a world comes up when one questions the difference between an “ambience”1 and a mere group of objects. However, by analysing the term “world” under the lens of narratology,2 it is possible to find some useful details that highlight the fundamental role of the relations between codes and languages in the database. The narratological theory struggles in defining the term “world”, especially when the examined object is a fictional one.3

The observation of the term storyworld, used by critic Mary-Laure Ryan to describe the space projected by the events - or the relations - between the different compositional elements of a world, focuses the attention on the very temporal feature of worlding.4 A world must endure over time, and its codes must work as temporal agencies in the space in which they act, or by quoting Ryan “it is not just the spatial setting where a story takes place, it is a complex spatio-temporal totality that undergoes global changes. Put more simply, a storyworld is an imagined totality that evolves according to the events told in the story.”5

In Ryan’s analysis, the relations between single elements must be recognized as events, in a way to pass over time and, therefore, become agencies able to shape new languages. Codes cannot be mere objects that stand in a frozen state, they need to create relations between them, they need to be in motion and become temporal elements.

As Bergson noted in The Creative Evolution (2005), an environment that dies and reborns at every moment lacks the fundamental element that distinguishes the very life of a world, namely evolution. Evolution, for Bergson, is the temporal trait that unites the events of the past with the present, which allows one to speak of a true duration in time. Continuity in change, temporal duration and the preservation or modulation of the past in the present are, thus, fundamental traits for there to be a dynamic world.

In contemporary studies, the concept of lore emerged from the field of research in narratology and game studies in an attempt to move the idea of world-building to a deeper level. The lore is a complex system of narrative elements that interact with each other, not only as symbols but also through temporal activities.6 Characters, objects, artefacts, movements, events in time, rituals, dress codes and sounds are an integral part of the lore of a world. It is a network of elements that exist beyond the main events of the story arc narrated in a fictional space, making it a structure that endures over time which becomes impassive to the main characters’ actions. For instance, the world of the game Dark Souls is a complex and decayed structure in which every main event is already passed; the overwhelming silence, sonically designed, portrays the echoes of a world that exists beyond times, even in the form of ruins. Traces of ancient civilizations and cultural beliefs are scattered not only on the map but also in sounds, objects, ambiguous dialogues and the shape of spaces, morphing the player into an explorer and gatherer of information.

These analyses in narratology highlight the role of time in the relations between objects in worlding. The storyworld and subsequently the lore, are the two fundamental aspects in the definition of a functional world, by creating a chronological net of connection in a common group of codes. In the construction of game spaces and narrations, the lore works as an enhancer in terms of immersivity of a world. The user becomes an integral part of such ambience, by connecting and understanding the processes that stand behind the experience that it is perceiving.

Detail from Dark Souls III: The Ringed City (DLC), FromSoftware, 2016-2017

Discovering the archaeology, the history and the past of the worlds we inhabit is an operation that goes hand in hand with the possibility of providing horizons of the future.

A world, for it to be called such, needs a certain degree of persistence over time. This is not just to underline the obvious fact that the world, as a horizon of meaning, cannot and must not disappear for no apparent reason, but also to stress the important role that temporality plays in world-building. Discovering the archaeology, the history and the past of the worlds we inhabit is an operation that goes hand in hand with the possibility of providing horizons of the future. Temporality, in this sense, is the lifeblood capable of constantly renewing the bonds between the different codes that shape the databases of a world. Three important criteria, therefore, emerge from these analyses: persistence, resistance and ductility. As Mark W. Bell has noted

"A virtual world cannot be paused. It continues to exist and function after the participant has left. Persistence separates virtual worlds from video games such as Pac-Man or Galaga. This persistence changes the way people interact with other participants and the environment. No longer is one participant the centre of the world but a member of a dynamic community and evolving economy. A participant has a sense that the systems in the space (environment, ecology, economy) exist with or without a participant’s presence."7

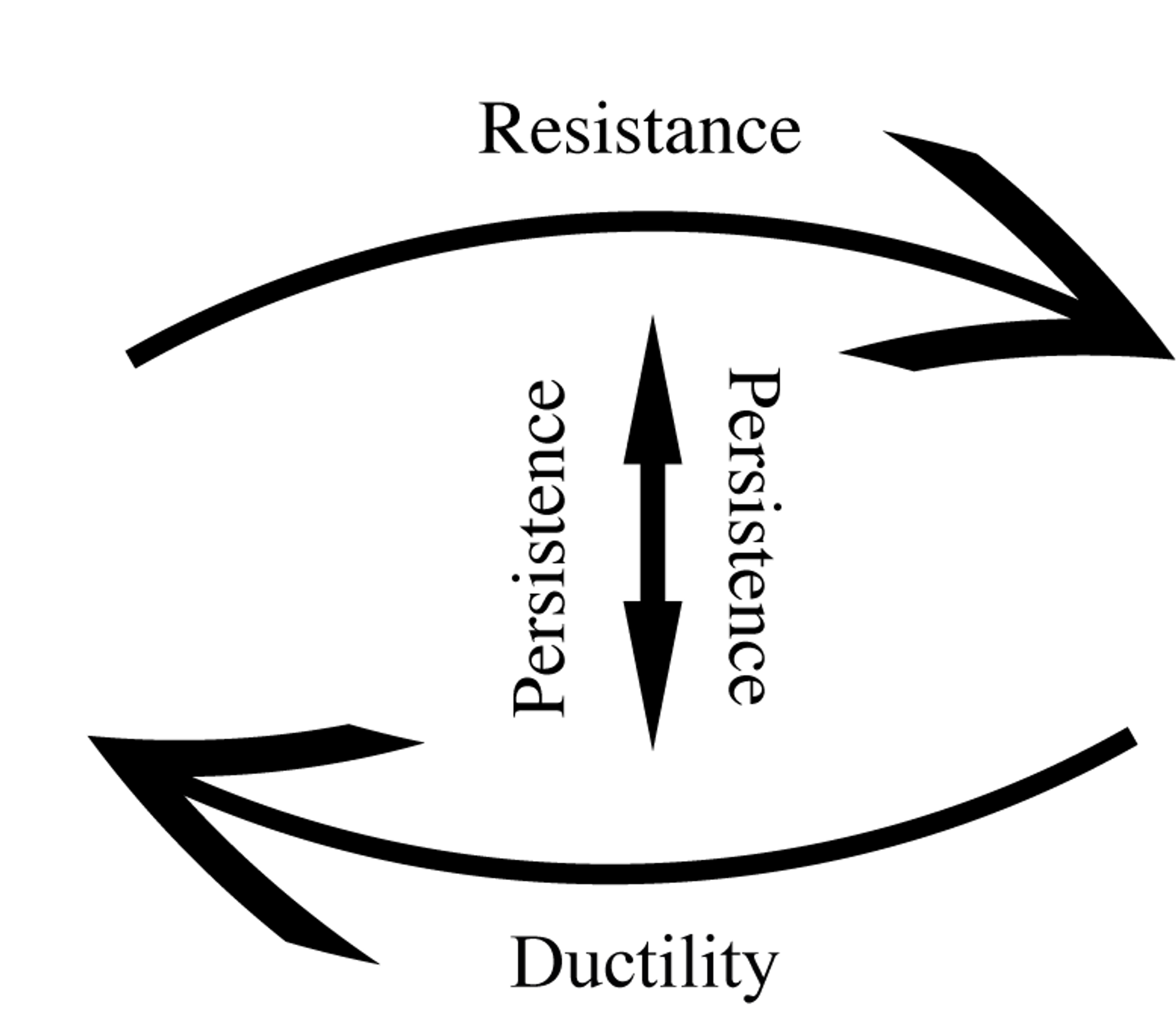

Persistence is the assurance that comes from understanding that the world possesses its own specific temporalities, not entirely reducible to the chronologies of its inhabitants. The fact that worlds can virtually survive through time is a fundamental assumption not only from an ecological point of view, but also from a structural and methodological one. The complexity and importance of a world, however, also necessitates resistance. Resistance is the set of resources a world possesses to cope with the changes that occur within it. A world can certainly persist unaltered in its main aspects, but even then it needs to be able to respond to agents and events that change its conformation back to its point of origin. Persistence and resistance cross each other by engaging in a strange temporal dance. Resistance is functional in bringing the frame of meaning that permeates a world back to its stability and points of reference. It is a set of reactive forces that can be unconsciously relied upon when inhabiting a world. Knowing that a world has survived worse events - again, the importance of history and archaeology - allows one to speculate and collaborate in building a common future.

Resistance and ductility follow a specular temporal path. While the former sketches a future by working on the past, the latter, on the contrary, builds a future by reworking the past.

As a counterbalance to resistance, the ability of a world to be malleable to changes and modifications is equally important. In fact, it would be very restrictive to try to define a world by its sole ability to bring all events back to a state of stability, eliminating every possible internal dynamic, every possible revolutionary drive. Parallel to the reactive forces of resistance, we see the active forces of ductility. These are the different ways in which a world makes changes of its own, excels at the upheavals that run through it, without, however, failing. Always close to dragging it to the zero point of destruction, the active forces of ductility make it possible to rewrite the past, the history of a world from its possible future openings. Resistance and ductility follow a specular temporal path. While the former sketches a future by working on the past, the latter, on the contrary, builds a future by reworking the past. Flexibility and the ability to adapt to new things that emerge within it draw a division between the different worlds. Ductility, persistence and resistance form a conceptual triangle within which the different worlds can be distinguished.

Resistance-Persistence-Ductility scheme.

So far we have placed the emphasis explicitly on a purely temporal side. But who makes these changes? Or who is able to respond to these changes? In fact, we have left empty the very important but difficult-to-occupy place that belongs to the subjects of these actions. For this reason, it is worth going back to the starting point, that is, returning again to the concept of lore.

Read the entire "How to Create a World" column by Davide Tolfo & Nicola Zolin.

Bio

Davide Tolfo writes about philophy and contemporary art, he has published for Marsilio Editore, NOT, LaDeleuziana, Mimesis and Philosophy Kitchen. In parallel, he has also worked with artist Shubigi Rao for the Singapore Pavilion at the 59th International Art Exhibition - La Biennale di Venezia in 2022.

Nicola Zolin is a researcher and sound designer, he is also co-founder of the experimental label Rest Now!. He writes about music, gaming, theory, visual arts and the intersections between them. He has published for many magazines and webzines, including Cactus Magazine, NOT and LaDeleuziana.

Notes

1 On the difficulty of defining an ambience, a milieu, and its boundaries, see the following passage from Deleuze and Guattari's A Thousand Plateaus: «Every milieu is vibratory, in other words, a block of spacetime constituted by the periodic repetition of the component. Thus the living thing has an exterior milieu of materials, an interior milieu of composing elements and composed substances, an intermediary milieu of membranes and limits, and an annexed milieu of energy sources and actions-perceptions. Every milieu is coded, a code being defined by periodic repetition; but each code is in a perpetual state of transcoding or transduction. Transcoding or transduction is the manner in which one milieu serves as the basis for another, or conversely is established atop another milieu, dissipates in it or is constituted in it. The notion of the milieu is not unitary: not only does the living thing continually pass from one milieu to another, but the milieus pass into one another; they are essentially communicating. The milieus are open to chaos, which threatens them with exhaustion or intrusion» Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari, A Thousand Plateaus. Capitalism and Schizophrenia (Minneapolis, London: University of Minnesota Press, 2015), 313.

2 The term narratology refers to the study of narrative and its structures, by also analysing the different methods in which a narration could affect the perception of the audience.

3 Jirǐ Koten, “Fictional Worlds and Storyworlds: Forms and Means of Classification,” In: Four Studies of Narrative, ed by Bohumil Fort, Alice Jedličková, Jirǐ Koten, and Ondrej Sládek (Prague: Institute of Czech Literature, 2010), 58-67.

4 Marie-Laure Ryan, “The Aesthetic of Proliferation”, in World Building. Transmedia, Fans, Industries, ed. Marta Boni, (Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2017).

5 Ivi, 33.

6 Describing the World of Warcraft universe, Tanya Krzywinska defines lore as the symbolic and mythological order in which players find themselves. The term lore emphasises precisely the fact that it is not a passive background; players with their interests, curiosity and ways of playing contribute to this symbolic order, see Tanya Krzywinska, “World Creation and Lore: World of Warcraft as Rich Text”, in Digital Culture, Play, and Identity. A World of Warcraft Reader, ed. Hilde G. Corneliussen and Jill Walker Rettberg (Cambridge, London: The MIT Press, 2008), 137-138.Commenting on this essay, Sky LaRell Anderson adds: «Lore is a type of mythos: it consists of any element of the game—text, visuals, or other design elements—that contextualises a game’s world. Primarily inspired by the world building of tabletop RPGs such as Dungeons and Dragons, lore offers players a feeling that the diegetic world has existed long before them and will exist long after them» (Anderson Sky LaRell. “The Interactive Museum: Video Games as History Lessons through Lore and Affective Design”, E-Learning and Digital Media 16, no. 3 (May 2019): 180. https://doi.org/10.1177/2042753019834957.)

7 Bell, W. Mark. “Toward a Definition of Virtual Worlds”. Journal of Virtual Worlds Research. 1, no. 1 (July 2008): 3.

Bibliography

Anderson Sky LaRell. “The Interactive Museum: Video Games as History Lessons through Lore and Affective Design”, E-Learning and Digital Media 16, no. 3 (May 2019): 177–95. https://doi.org/10.1177/2042753019834957.

Bell, W. Mark. “Toward a Definition of Virtual Worlds”. Journal of Virtual Worlds Research. 1, no. 1 (July 2008): 2-5

Bergson, Henri. Creative Evolution. Translated by Arthur Mitchell. New York: Random House, 2005.

Deleuze, Gilles and Guattari, Félix. A Thousand Plateaus. Capitalism and Schizophrenia. Minneapolis, London: University of Minnesota Press, 2015.

Koten, Jirǐ. “Fictional Worlds and Storyworlds: Forms and Means of Classification,” In: Four Studies of Narrative, ed by Bohumil Fort, Alice Jedličková, Jirǐ Koten, and Ondrej Sládek. 58-67. Prague: Institute of Czech Literature, 2010.

Krzywinska, Tanya. “World Creation and Lore: World of Warcraft as Rich Text”, in Digital Culture, Play, and Identity. A World of Warcraft Reader, edited by Hilde G. Corneliussen and Jill Walker Rettberg. Cambridge, London: The MIT Press, 2008.

Ryan, Marie-Laure. “The Aesthetic of Proliferation”, in World Building. Transmedia, Fans, Industries, edited by Marta Boni, 31-46. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2017.