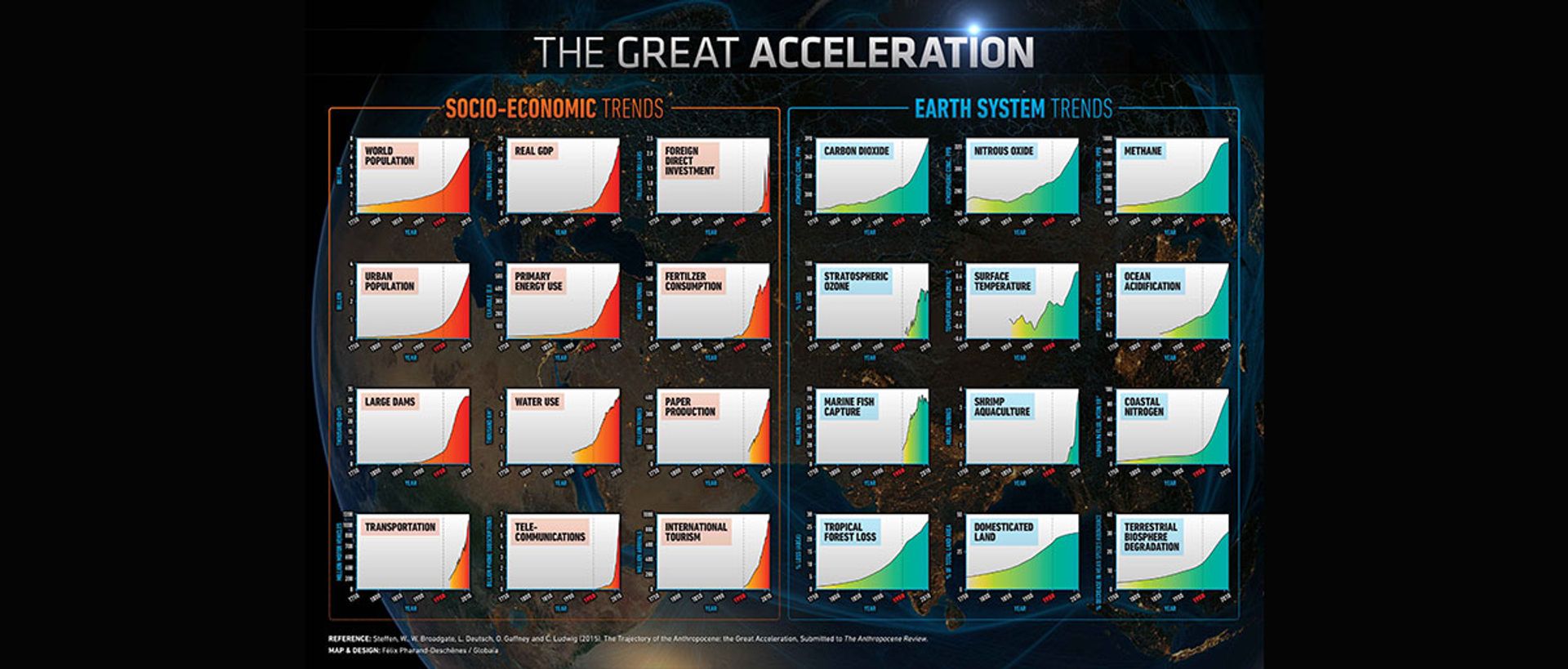

Current estimates suggest that the world’s biodiversity intactness is at 75% overall,1 far below the 90% limit that scientists believe is safe.2 Over a million of the plant and animal species in the world are at risk of extinction.3 Simultaneously carbon levels are at the highest they have been and are rising. Through the Stockholm Resilience centre’s dashboard on the “Great Acceleration” we see a delicate balance across a vast range of species and landscapes has been rapidly altered in the past 70 years. There is a consistent pattern across socio-economic anthropogenic and natural systems from a range of habitats and biospheres showing a rapid increase in this time frame. In what has been termed as the “Great Acceleration”, the Stockholm Resilience centre has found that GDP has risen exponentially, as has fertiliser consumption and water use while tropical forest loss rates, carbon dioxide and methane levels, domesticated land have all too shot upwards. Humankind’s behaviours are impacting the planet’s wider species at every scale,4 from macro impacts on the oceans, right down to the smallest insects and far-flung landscapes being blighted by microplastics.

Charting the "Great Acceleration" in human activity from the start of the industrial revolution in 1750 to 2010, and the subsequent changes in the Earth System. Illustration: Steffen et al. 2015. and F. Pharand-Deschênes/Globaia

Humankind’s behaviours are impacting the planet’s wider species at every scale, from macro impacts on the oceans, right down to the smallest insects and far-flung landscapes being blighted by microplastics.

The scale of the biodiversity crisis is difficult to visualise in a simple graphic, given the complex, interconnected systems it is comprised of, hence the success of the “blue marble” imagery associated with Lovelock’s “Gaia theory” showing the Earth as a single, tangible entity. A more recent attempt has been made by Prof. Miles Richardson who has sought to develop a similar graphic to represent biodiversity loss and the “greying” of planet Earth.5 Perhaps not yet as well-known as the original stripes, but an important attempt that is gaining traction. For too long, biodiversity loss has faded into the background as compared to other pressing issues such as climate change. The time has come for it to take central stage alongside carbon reductions for the sake of humanity and nature more widely.

Biodiversity loss has faded into the background as compared to other pressing issues such as climate change. The time has come for it to take central stage alongside carbon reductions for the sake of humanity and nature more widely.

Biodiversity stripes, Miles Richardson. LPI 2022. Living Planet Index database. 2022 www.livingplanetindex.org

While the world governments and media gather in Sharm-el-Sheikh reviewing progress on commitments made at COP26 last year and nudging the agenda forward a touch, from an outsider’s perspective,6 the spotlight still fails to fully shine on biodiversity. While the subject is being covered to some extent at COP27, there will be no explicit requirement to make a committed action plan for this serious loss. Instead, the primary function of COP27 is to seek implementation commitments in line with the Paris Commitment signed in 2015, which looked to limit global heating to no more than 1.5°C. Ahead of the conference, the UN has already stated in its latest Emissions Gap report that there is “no credible pathway” to keep to the limit of 1.5°C.7 If anything, 1.5°C seems to have been etched in peoples’ minds as an acceptable threshold, not the tipping point it is expected and feared to be. It now seems very likely that we may exceed 2°C of global heating before long, unfathomable in terms of what this means not only for humans but also for nature.8 If this is all while COPs have been running for climate for some 27 years - and on biodiversity for 15 - what does this say of the usefulness of these bureaucratic fiestas?

1.5°C seems to have been etched in peoples’ minds as an acceptable threshold, not the tipping point it is expected and feared to be.

At COP27 there is a “Nature Zone” holding conversations and moving the agenda for nature forward. Biodiversity is also to be presented as one of the 11 theme day topics at COP27, showing some progress compared to COP26, where nature and land use shared a day. However, the only theme with fewer agenda items this year is ACE & Civil Society. It is also telling that biodiversity day’s placement in the roll call; on the second to last day of the conference. A day where most of the decision-making delegates will already be huddled around tables and in dark corners thrashing out details of deals9 in anticipation of the closing commitments and agreements needing to be made by the end of day 17th November. At COP26, this process was memorably nail-biting, with Alok Sharma shedding a tear in frustration and a not fully realised10 fear that the whole conference would result in no consensus at all in the closing hours. One cannot help but wonder if - since “Solutions day” falls the day after it - biodiversity is being presented as a distracting, lighter afterthought to the main portion of proceedings. It does appear to critical onlookers like myself that biodiversity is still not really at the heart of the conference. I do hope that I am wrong, especially as the conference is being held in Africa, where land is already significantly degraded and where biodiversity loss is already being very keenly felt.11

One cannot help but wonder if [...] biodiversity is being presented as a distracting, lighter afterthought to the main portion of proceedings.

What does give me hope is that at least conversations on biodiversity loss have started, and the topic will be addressed in full detail later on, at the UN’s next half of this year’s iteration of the Biodiversity Conference COP15. The location and dates for this event have been altered several times, with postponements blamed upon Covid-19.12 This conference was split in two, with an online portion in October and the in-person conference in Montreal from the 7-9 December. There, delegates will probably try to pick up momentum once again from the earlier proceedings, where world nations agreed to the landmark (again under-reported)13 of the Kunming Declaration that is

"Acknowledging with grave concern that the unprecedented and interrelated crises of biodiversity loss, climate change, land degradation and desertification, ocean degradation, and pollution, and increasing risks to human health and food security, pose an existential threat to our society, our culture, our prosperity and our planet."14

And is committing to

"Ensure the development, adoption and implementation of an effective post2020 global biodiversity framework, that includes provision of the necessary means of implementation, in line with the Convention, and appropriate mechanisms for monitoring, reporting and review, to reverse the current loss of biodiversity and ensure that biodiversity is put on a path to recovery by 2030 at the latest, towards the full realization of the 2050 Vision of “Living in Harmony with Nature”."15

While COP15 and COP27 are indeed separate conferences, and likely attended by overlapping but varied crowds with differing priorities and agendas, the reality is that nature and global temperatures are intrinsically connected, with reciprocal relationships as Lovelock describes so well. An effect on one can impact the other, for better or worse. This interconnectivity has been acknowledged by the landmark first joint publication between IPBES and UNEP last year, stating that neither biodiversity nor climate change “will be successfully resolved unless both are tackled together.”16

We must remember that climate change is not the only driver of biodiversity loss, but one of many.

Given this intrinsic interconnectivity, it is not surprising that there are solutions that can simultaneously reduce carbon emissions while also supporting biodiversity gains. For instance, there are co-located renewable energies with biodiversity supporting land management at a macro scale or even biosolar roofs that act at the micro scale. Moreover, the onshore Whitelee Windfarm in Glasgow, that I coincidentally visited while in Glasgow for COP26, has generated almost 90% of total annual household energy consumed in Scotland and also has an ecology team working to monitor the wildlife on site. It is open as a park for people to enjoy and witness nature and renewables existing in harmony.

We must remember that climate change is not the only driver of biodiversity loss, but one of many. We cannot only address biodiversity loss in pursuit of in parallel addressing climate change, this will likely not be good enough for restoration of biodiversity to safe limits. Other drivers such as land use change, food and agriculture and even “direct exploitation of organisms”17 could also be addressed as potential solutions.

Whitelee Windfarm in Glasgow, photo of the author

Not only is nature being looked at in fragmentation across COPs, the tone and worldview are innately exploitative still. For instance, at COP26 parties recognised:

"The importance of ensuring the integrity of all ecosystems, including forests, the ocean and the cryosphere, and the protection of biodiversity.

Emphasized the importance of protecting, conserving and restoring nature and ecosystems, including forests and other terrestrial and marine ecosystems, to achieve the long-term global goal of the Convention by acting as sinks and reservoirs of greenhouse gases and protecting biodiversity, while ensuring social and environmental safeguards.

Recognized the importance of protecting, conserving and restoring ecosystems to deliver crucial services, including acting as sinks and reservoirs of greenhouse gases, reducing vulnerability to climate change impacts and supporting sustainable livelihoods, including for indigenous peoples and local communities."18

If we analyse the text, we realise that the focus and emphasis on the protection of nature outlined by those attending COP26 was mostly self-motivated. Prioritising aspects such as “ensuring social and environmental safeguards […] acting as sinks and reservoirs of greenhouse gases […] to deliver crucial services”19 ostensibly is to serve the human populations depending on nature. In fact, the frame of Biodiversity Day for COP27 focuses on “nature and ecosystems-based solutions”,20 which sees nature as a service to humans’ gain first and foremost. It is covered again on Solutions Day, where nature is seen as a great solution rather than an entity deserving to flourish in its own rights. But what if we decentre humans as the core driver for the preservation of nature? What if we, instead, seek to pursue nature’s thriving for nature’s own sake, whatever the measurable, tangible, or even any benefit to us is in the short term? What if the goal was not only about restoring nature but, indeed, moving the dial further, towards what Michael Pawlyn and Sarah Ichioka describe as the “flourishing” of all in a regenerative system?21

But what if we decentre humans as the core driver for the preservation of nature? What if we, instead, seek to pursue nature’s thriving for nature’s own sake, whatever the measurable, tangible, or even any benefit to us is in the short term?

Seeing biodiversity and ecosystems divided up between COPs makes manifest the truth for how humankind sees nature today; a largely providing a service which we can tinker with in specific ways and have predictable end-results. The reality is that ecosystems are far more complex than this nature-as-service approach relies upon, often with knock-on impacts not well understood by humans, or at least outside of peoples of indigenous cultures who live close to, and symbiotically with, the land. It is frequently noted that indigenous people protect over 80% of the world’s remaining biodiversity while only comprising 5% of the world’s population.22 Those who have the closest relationships with nature are the same people who seek to protect it. Fostering a closer connection with nature has been found time and time again to lead to improvement for humans and nature.23

What then of the urban places where so many of us spend our lives? 68% of the world’s population is expected to live in urban areas by 2050, most likely further “greying” land if unchecked. We know that urbanisation can be positive for the reduction of carbon emissions and improved efficiencies of scale across systems. However, nature can be disadvantaged if we forget to support it while expanding our cities. Therefore, designers have a responsibility to support greater access to nature in order to facilitate a deeper understanding of our reliance on nature. This could consequently help supporting biodiversity.24 This could be achieved through the collaboration between built environment professionals: architects, landscape architects, ecologists, urban planners to ensure that we maximise every opportunity and limit unintended consequences wherever possible. We know nature-based solutions can support reductions in the urban heat island effect, pollution, carbon dioxide levels and groundwater run-off in extreme weather, so we should look to nature over technological solutions to maximise co-benefits. Nature-based solutions (NbS), however, should be seen for what they are: humankind acting to alter ecosystems for our own, with limited benefits. An alternate approach could be a “ruralisation”25 of the built environment. This approach seeks to reintegrate nature into the built environment. Perhaps this concept could overcome the limits of NbS. Ruralisation will require all built environment professionals to learn new solutions and be humble about their limits.

Nature-based solutions (NbS), however, should be seen for what they are: humankind acting to alter ecosystems for our own, with limited benefits.

We cannot avoid side-lining and failure to address the needs of nature any longer. As the Kunming Declaration stated, “putting biodiversity on a path to recovery is a defining challenge of this decade”,26 is it one we are willing to address with the urgency and radical change it requires? Could this be the moment for a positive tipping point in society’s outlook on the natural world and how much we rely upon it? There is hope, today in local English language dialects there are over 250 words for “woodlouse” (for instance “chucky pig” or “Monkey pea”, “cheesy bug” and so on). It seems that there is still capacity for us to live in harmony with nature, and maybe deep down we already know how to.

Read the entire "A Grassroots Organization at COP" column by ACAN (Architects Climate Action Network).

Bio

Kat Scott co-founded ACAN’s biodiversity focused group, called “Where the Wild Things Aren’t”. For work as dRMM’s Sustainability & Regenerative Design Manager, Kat develops strategies and conducts research in light of the studio’s “Architects Declare Climate and Biodiversity Emergency” commitments. Kat is passionate about mitigating the impacts of construction on the wider environment and advocates for decarbonisation of the industry together with a shift towards more regenerative systems. She contributes to sustainability and regenerative design innovation on design projects in the UK and internationally, as well as working on a voluntary basis on knowledge-sharing and advocacy, while managing ongoing chronic illness. Personally, she is today most inspired by Tricia Hersey and is learning the art of rest and recuperation as an act of resistance.

Notes

1 Ashworth, J. Analysis warns global biodiversity is below ‘safe limit’ ahead of COP15 (2021) [link]

2 Idem.

3 Out of over 8 million known plant and animal species. IPBES, Global Assessment Report on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (2019). [link]

4 Bovin, N. L., Zeder, M. A, et al. Ecological consequences of human niche construction: Examining long-term anthropogenic shaping of global species distributions, PNAS Vol. 113, No. 23, (2016).

5 Richardson, M. Biodiversity stripes: A journey from Green to Grey. August 10th 2022, [link]

6 The author will not be attending COP27. It is actually very difficult to get hold of passes to attend, with limited numbers per country and per organisation, with only specific categories of organisations able to apply to receive tickets. The limit number of persons at the Conference will know far better the true sense of how things have gone, while perhaps more importantly, we at home can get glimpses by joining online events and reading snapshots in the press.

7 UNEP, Emissions Report Gap 2022 - The Closing Window: Climate Crisis calls for rapid transformation of societies, (27th October 2022), [link]

8 To read more on predictions of what temperature rises at different levels may mean for society and nature see, WWF, Backgrounder: Comparing Clmiate impacts at 1.5oC, 2oC, 3oC and 4oC (2017) [link]. Tipping points are expected to make effects that current models struggle to predict.

9 Based on broadcast footage from COP26 and interviews with delegates at the time.

10 In the final hours of COP26, India and China successfully sought to weaken the, until then, agreed pledge to end coal and fossil fuel subsidies in the Glasgow Climate Pact. There was relief that the Pact was finalised, but frustration at the alteration. As covered in the Financial Times; Hook, L., Hodgson, C. and Pickard, J. India and China weaken pledge to phase out coal as COP276 ends, Financial Times (online) 13th November 2021, [link]

11 UN FAO Review of Forest and Landscape in Africa (2021), [link] Accessed 8 November.

12 Hard to imagine that the same would happen for the Climate COP, which continued through a fairly significant covid-19 wave in Glasgow last year with Scottish restrictions in place. See summaries of postponements here: [link] and [link]

13 A quick comparison – the author found there are 2,060 results on Google News for anything relating to Kunming Declaration that was agreed to in October, compared to the 200,000 results that appear for items referencing “UN emissions gap report 2022” released one week before this article was written.

14 The Kunming Declaration is available at this link.

15 Ibid, 3.

16 Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES) and the UN’s Environmental Program (UNEP), Tackling Biodiversity & Climate Crises Together and Their Combined Social Impacts, (June 2021), [link]

17 From WWF summary on IPBES Global Assessment Report; [link]

18 United Nations Climate Change, The Ocean. [link]

19 Ibid.

20 Ibid.

21 Sarah Ichioka, and Micheal Pawlyn, Flourish: Design Paradigms for our Planetary Emergency (Chicago: Triarchy Press, 2021).

22 UNEP, [link] Accessed 7th November 2022

23 For a summary of wide-ranging research on this subject, see Dasgupta, P. The Economics of Biodiversity: The Dasgupta Review (2019) available at [link]

24 Ibid.

25 This term feels more comfortable than “rewilding” to me for an application in urban built environments. Rewilding, I believe, (and feel suitably well informed after attending “Rewilding the Mind” symposium on the subject having listened to Alastair Driver talk on Rewilding Britain’s work) is a term which really only makes sense at large scales where fauna can be allowed to thrive and act as keystone species to their fullest. I am not sure we are ready yet to embrace wolves and boars as friends in our cities and towns.

26 Kunming Declaration, 3.

Bibliography

Bovin, N. L., Zeder, M. A, et al. Ecological Consequences of Human Niche Construction: Examining Long-term Anthropogenic Shaping of Global Species Distributions, PNAS Vol. 113, No. 23, (2016). [link]

Ichioka, Sarah and Pawlyn, Micheal. Flourish: Design Paradigms for our Planetary Emergency. Chicago: Triarchy Press, 2021.